The Paradox

The paradox of the American Army’s training in speed and mobility and the strategic tradition of U.S. Grant influenced the final campaign in Germany just as they had the campaign in France. This is one of the Russell Weigley in Eisenhower’s Lieutenants asserts that the American strategic tradition of U.S. Grant emphasized direct confrontation and defeat of the enemy’s major forces. He asserts the development of this tradition by officers assigned to the Leavenworth schools was influenced by the Civil War and World War One and the Army’s experience as a frontier constabulary force. He develops this theory alongside his discussion of the formation of the highly mobile and less powerful forces that the Army would deploy in World War Two and how this paradoxical combination of doctrine and force determined by conflicting legacies “put the army at cross purposes with itself…as it began to prepare for European War.”[i]

Crossing the Siegfried Line

Crossing the Siegfried Line

The dogma of the Leavenworth School emphasized that “victory in large-scale war depends on a strategy of direct confrontation with the enemy’s main forces in order to destroy them.”[ii] This was not in itself different than the thought of contemporary European armies influenced by Clausewitz; but the Americans differed from the Europeans “in the extent to which they expected overwhelming power alone, without subtleties of maneuver, to achieve the objective.”[iii] The tradition developed from an emphasis on Ulysses S. Grant’s campaign in Virginia which understood that Grant had “defeated the armies of the Confederacy through head on assault by overwhelming strength to destroy them, so that in any future great war the United States would seek the destruction of the enemy armed forces by similar means.”[iv] It is perplexing that the Army failed to truly appreciate William Tecumseh Sherman’s use of strategic maneuver on the offense with the goal of destroying the enemy’s army. The fact that the Army failed to incorporate those lessons into its strategic thought, even as it built forces that were better suited to Sherman’s campaign is one of the contradictions of American military thought.[v]

Grant’s tradition was put into practice by Pershing in World War One to the extent that he could influence allied strategy, with mixed results.[vi] The reduction of the St Michel Salient and Meuse-Argonne offensive, though aided by German withdraws and achieved with high casualties, helped convince the Germans that the war was lost.[vii] “Only in late 1918 did the veteran American divisions show the same degree of tactical skill as their Allied and German counterparts, and the lessons came by bloody experience.”[viii] Pershing’s campaigns were bloody, but they came at a when maneuver had again become part of the war, and at the point where the Germans were beginning to collapse. George Marshall warned about “generalizing about modern warfare from their 1918 experiences against a German army already stumbling into exhaustion.”[ix] Yet for “the American military, the First World War confirmed the doctrines of concentration and of fighting for complete victory, and out of the battlefields of Europe came the foundations of strategic faith….”[x] Weigley notes that: “In strategy, most American soldiers believed, the modern mass army left frontal assault as the only recourse.”[xi]

While Grant’s tradition remained a dominant feature of American strategic thought, the Army was becoming a mobile army whose divisions were to be “tough and lean.”[xii] General Leslie McNair reorganized the structure of the infantry division and later that of the armored divisions. The heavy “square” infantry division of the First World War was reorganized with three infantry regiments and supporting elements and was characterized by its mobility than its sustained combat power. McNair reorganized the armored divisions into lighter, though extremely flexible organizations built around the “Combat Command” and the tank was viewed as viewed as an instrument of exploitation, not a means to defeat enemy armor. The result was an army formed “upon the principle of mobility and its lack of sustained combat power…did not serve it so well when it faced resolute and skillful enemies in strong defensive positions….”[xiii]

The new divisional structures were both mobile and flexible but in the context of the European campaign were wanting in sustained combat power. Peter Mansoor comments that divisions “literally fought themselves out in constant operations.”[xiv] At the same time he takes issue with Weigley on the staying power of U.S. divisions commenting on the efficiency of the American individual replacement system.[xv] A U.S. Army study commented that in direct assaults against a emplaced enemy that “heavy casualties in such operations were more than the triangular division could sustain, with the result that the entire division was often rendered combat ineffective….”[xvi] McNair’s reorganization ignored General Chaffee’s 1941 admonition that armor must be organized into corps and employed in mass using not “hundreds but thousands of tanks…” calling the failure to train and organize “an adequate number of command echelons and corps troops to ensure proper employment and timely supply for these larger armored formations in active operation is indefensible.”[xvii]

To further complicate the American situation, the application of Grant’s tradition failed to take into account the principle of mass or concentration, which was vital to the success of a strategy of direct confrontation. The theory demanded that the Americans have enough troops divisions to keep up pressure everywhere. Grant had such power at his disposal, Eisenhower did not. The thought that “if the United States applied its superior power everywhere it must be able to rupture the defenses somewhere,”[xviii] was dominant. But to be successful it required overwhelming superiority in numbers and firepower. This strategy was in conflict with the Army that the Americans built to pursue the war, and in conflict with one of the more influential prewar American thesis on the subject, Infantry in Battle. This treatise stated:

“Generalship consists at being stronger at the decisive point-having three men there to attack one. If we attempt to spread out so as to be strong everywhere, we shall end up being weak everywhere. To have real main effort-and every attack and attack unit should have one- we must be prepared to risk extreme weakness elsewhere.”[xix]

It was an army designed for Sherman’s campaigns in Georgia and the Carolina’s, not Grant’s Virginia campaign. It was best suited to campaigns of strategic maneuver and concentration rather than frontal assaults along a broad front. Its organization called for this and this fact was recognized before the war.[xx] Weigley notes that the “paradoxical commitment to a power drive strategy of head-on assault in an army shaped for mobility further contributed to the prolonging of the war by undermining the possible uses of mobility itself.”[xxi]

The theory of Grant, espoused by the Leavenworth school is fine there are sufficient forces to make it work. General McNair and Army planners initially planned for an Army of over 200 divisions. Such an army would have been able to execute the strategy without the problems experienced by the Allies in 1944 and 1945. Unfortunately the American Army was afflicted by the War Department’s decision in 1943 to limit the Army to 90 divisions.[xxii] The limitation on the number of divisions ensured that it would be “difficult or impossible once the battle of France was launched to rotate them out of line for rest or refitting.”[xxiii] This became a key consideration of allied planning by late 1944 because once the existing divisions were deployed to Europe or the Pacific there were no more to replace them. Drastic measures were taken to increase the number of infantry troops by speeding up the movement of the last available divisions to Europe and by combing troops out of the COMMZ and from the Army Air Force.[xxiv] Training programs were put in place to train tank crews and junior officers. Yet, these programs did not begin to put significant numbers of replacements into the line until March 1945.[xxv] Mansoor, a critic of Weigley, agrees with him on many points and notes that the “90 division gamble was a decision that cost the lives of numerous servicemen-primarily infantry replacements-in Europe in 1944 and 1945.”[xxvi] The decision to limit the number of divisions forced Eisenhower into a position where he frequently faced an equivalent number of German divisions to those that he could employ. This would be the case in at the beginning of 1945 despite the steady erosion of the German forces arrayed before him.

Leadership, Strategy and Tactics and the Performance of the Army

The Germans Employed the Jagdtiger in Small Numbers Against the American Onslaught

The Germans Employed the Jagdtiger in Small Numbers Against the American Onslaught

After the Bulge the Allies began their push to the Rhine. Eisenhower “interpreted the Ardennes as confirming the necessity for his broad front strategy, particularly in closing up to the Rhine all the way to Switzerland.”[xxvii] Hastings notes that the Wehrmacht “retained psychological dominance on the battlefield,”[xxviii] and that “Allied commanders remained fearful about exposing their flanks in attack, even when the Germans no longer possessed the resources or mobility to intervene with conviction.”[xxix] In many places GIs and their British counterparts in Montgomery’s 21st Army Group failed to take the initiative and often the Allied commanders “expressed dismay about the lack of aggression shown by their troops.”[xxx] Gavin noted in his diary that: “With better troops, I see no reason why we could not run all over them…Our American army means well and tries hard, but….it is untrained and inefficient… certainly our infantry lacks courage and élan.”[xxxi] Despite this the Allied armies, in particular the Americans, made headway and in many places when well led performed admirably.

The Eifel

Following the reduction of the Bulge Eisenhower allowed Bradley to begin to break the West Wall in the Eifel. After the attack began Eisenhower stopped Bradley short of a breakthrough in order to shift weight of the offensive to Montgomery in the north ordering 12th Army Group to revert to the defensive. Yet, Eisenhower allowed Bradley a “measure of freedom for limited attacks,”[xxxii] and Patton termed his “operations in the Eifel an “aggressive defense.””[xxxiii] The campaign was primary conducted against oddments of a number of Volksgrenadier divisions of 7th Army.

First Army was diverted on February 1st after making good progress in the Eifel to safeguard the right flank of 9th Army by capturing the Roer dams. Hastings notes that a “more flexible and imaginative commander-or one unconstrained by the demands of inter-allied relations-would have allowed Hodges forces to keep going to the river and delayed Montgomery for the necessary few days.”[xxxiv] However Bradley felt that Eisenhower “had little choice but to accede to Montgomery’s demand.”[xxxv] Bradley allowed 3rd Army to continue “probing attacks,” and 3rd Army advanced across the Eifel breaking through the West Wall at Prüm and Bitburg. For the first time the enemy showed “cracks in the admirable cohesion and discipline of the German army.”[xxxvi] Aggressive units of Patton’s 3rd Army were rewarded with dramatic advances. 4th Armored Division in “one bound covered 25 miles, taking 5,000 prisoners and killing several hundred Germans for the loss of 111 of its own men,”[xxxvii] and 10th Armored took Trier on 14 March. Patton called the campaign “a long hard fought fight with many river crossings, much bad weather, and a great deal of luck.”[xxxviii] Despite this there were problems in some formations. Hastings recounts how a platoon leader in a VII Corps unit told his commander during a crossing of the Sauer River that “These men have had it sir! They won’t budge for me or anybody else….”[xxxix]The G-3 of 6th Armored division noted that “some of our divisions are too sensitive to their flanks…the result of this is timidity…”[xl]

The Roer Dams, Grenade and Lumberjack

1st Army supported 9th Army by capturing the Roer river dams in preparation of Grenade. The inexperienced 78th Division was able to secure the dams with help from the veteran 9th Division, though not before the Germans had destroyed the release valves to “flood the Roer valley for about two weeks.”[xli] This delayed the start of Grenade but the Americans finally captured a prize that had eluded them the previous fall. The one truly notable aspect of this campaign was the continued erratic leadership of Hodges. Gavin called it “impatient” and it nearly cost the Commanding General of 78th division his command. Bradley’s aide, Major Hanson remarked that Hodges “was near exhaustion.”[xlii]

9th Army’s attack was conducted in concert with Operation Veritable of 2nd Canadian Army. The plan was that the two armies would clear the area west of the Rhine destroying as much of the enemy as possible in preparation for the crossing of the river. As such 9th Army remained under the operational control of Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. 9th Army crossed the Roer, hampered by the high waters and German resistance but captured Düren and München-Gladbach and closed up to the Rhine. The “rapid build-up enabled Simpson to maintain intense pressure and on the last Day of February his armor broke away.”[xliii] 9th Army met up with the Canadians eliminated elements of the German Army that remained west of the river. 9th Army took over 30,000 prisoners and killed an estimated 6,000, but substantial numbers were evacuated by skillful German commanders.[xliv] The greatest disappointment was that Grenade failed to capture any bridges over the Rhine. Montgomery turned down Simpson’s request to make a fast crossing of the Rhine at Urdingen, where there were few German troops.[xlv]

South of 9th Army the 1st and 3rd Armies launched Operation Lumberjack to attempt to envelope the German forces west of the Rhine in its sector in similar fashion to Grenade-Veritable. Facing weak German forces 1st Army made good progress capturing Cologne on March 5th. 3rd Army’s advance was exceptional. Its plan to cut off the Germans on the west bank worked almost to perfection despite poor roads, snow and the opposition of the 2nd Panzer Division.[xlvi] General Gaffney’s 4th Armored division, drove 40 air miles, captured 5,000 prisoners killed another 700 Germans, capturing much equipment with the loss of only 29 men killed.[xlvii] Bradley called the division’s performance “the most insolent armored blitz of the Western war.”[xlviii] Patton’s armor covered “56 miles in three days to reach the Rhine near its confluence with the Moselle.”[xlix] For the first time “senior officers and headquarters fell into the American bag,”[l] including the command post of LXVI Corps and the commander of LIII Corps. In these operations the bold use of maneuver and concentration by Simpson, Hodges and especially Patton exploited the natural strengths of their formations to achieve their objectives.

Remagen

Remagen Bridge

Remagen Bridge

1st Army’s swift advance and the chaos wreaked by Patton’s army led to the only instance in the campaign where the Allies captured a bridge over the Rhine intact. The Ludendorff railway bridge at Remagen remained and on 7 March 9th Armored division detached a task force from CCB to take the bridge before it could be blown. This force surprised the Germans and reached Remagen by 1300. General Hoge, hero of St. Vith, arrived quickly and ordered the capture the bridge as quickly as possible.[li] Hoge ignored orders to divert most of his troops to another crossing of the Ahr River and without orders “threw the rest of his armored infantry across the Rhine….”[lii] “In spite of the threat of the bridge being blown by the fleeing Germans, bold action by American infantry and engineers captured the bridge and established a bridgehead over the Rhine by 1630. III Corps ordered 9th Armored division to “exploit the opportunity,”[liii] and “within 24 hours they had 8,000 men across.”[liv] Hodges exploited the opportunity and pushed the 9th, 78th and 99th divisions across the river where they continued to enlarge the bridgehead while fighting off fierce German counter-attacks. By 24 March 1st Army had “three corps, six infantry divisions, and three armored divisions across the Rhine River.”[lv] The best German formations “arrived piecemeal and spent themselves in the same way, mustering only limited, scattered counterattacks instead of any major blow.”[lvi]

The Remagen crossing was not welcomed by all and restrictions were placed on 1st Army as it enlarged the bridgehead. Carlo D’ Este saw Remagen as “typical of the lack of connection between SHAEF and its subordinate elements.”[lvii] “Pinky” Bull, the SHAEF G-3 was at Bradley’s headquarters when the Bradley was informed of the crossing. Bull told Bradley that the Remagen crossing “just doesn’t fit in with the plan.”[lviii] Bradley recalled telling Bull: “What the hell do you want us to do,” I asked him, “pull back and blow it up?”[lix] During the next few days however “Bull’s unbending skepticism infected Eisenhower himself.”[lx] And by March 9th Bull informed Bradley that Eisenhower “did not want the Remagen bridgehead expanded beyond the ability of five divisions to defend it.”[lxi] The decision to favor Montgomery’s crossing of the Rhine by detaching divisions from 12th Army Group to support it caused consternation among Bradley and his commanders who feared that Montgomery would “use most of the divisions on the Western Front, British and American, for an attack on the Rhine plains…and the First and Third Armies be left out on a limb.”[lxii] Liddell-Hart noted that the order was “all the more resented because the U.S. Ninth Army…four days earlier, had been stopped by Montgomery from trying to cross the river immediately, as its commander, Simpson, desired and urged.”[lxiii]

Patton’s 3rd Army Crossed the Rhine on the Fly at Oppenheim

Patton’s 3rd Army Crossed the Rhine on the Fly at Oppenheim

Remagen’s aftermath showed Eisenhower’s continued commitment to the broad front, to closing up to the Rhine along its entire length, and his inordinate fear of German counter-stokes. He remained “fearful that, as long as some German forces survived on the Western side of the Rhine, the potential existed for another potential unpleasant surprise, a counter-attack across an exposed American flank.”[lxiv] The facts belied the situation and Model, commander of Army Group B “had not only given up on trying to eliminate the American bridgehead at Remagen but had covertly begun ordering large elements of Army Group B to evacuate the Rhine and cross the river.”[lxv] This decision resulted “in a lost opportunity to have established a larger bridgehead across the Rhine.”[lxvi] It was another example of Eisenhower’s failure to exploit opportunity when it presented itself and of a desire more to not lose the war than to win it. Despite this “Remagen bridge was one of the great sagas of the war and an example of inspired leadership.”[lxvii] Wilmont called it “a brilliant coup,”[lxviii] a thought echoed by Liddell-Hart.[lxix] The German response to rush numerous units to contain the bridgehead made the Allies task when they crossed the Rhine at other points “much easier than they had anticipated.”[lxx]

Patton’s Saar-Palatinate Campaign

Patton’s 3rd Army attacked the Saar-Palatinate in concert with the 7th Army with the intent of assailing the West Wall from the rear and trapping the remnant of the German Seventh Army and the German First Army. 7th Army assaulted the West Wall while Patton’s army began its assault on 13 March with the XII and XX Corps attacking into scattered German resistance. With the infantry making the breakthrough both corps unleashed their armored divisions in an exploitation role. Patton’s attack was so successful that he was allowed to adjust his assault to carry it into 7th Army’s zone to encircle the collapsing German Army. In an unusual command and control move Devers of the 6th Army Group gave Patch and Patton “the authority to communicate directly with each other, bypassing their different army group headquarters.”[lxxi] Large scale surrenders began to take place for the first time, including that of 3 Volksgrenadier divisions and the remnants of 2nd Panzer division.[lxxii]

US Soldier Standing Watch over Disabled Jagdtiger

US Soldier Standing Watch over Disabled Jagdtiger

Patton was urged on by Bradley, who warned him about “the danger of losing his divisions to Montgomery if he did not secure a Rhine crossing.”[lxxiii] Patton got his engineers and bridging equipment up quickly and Bradley ordered him to “take the Rhine on the run.”[lxxiv] On March 19th alone the Third Army overran more than 950 square miles of territory.”[lxxv] Third Army “cleaned up the west bank of the Rhine all the way south to Worms and Speyer; Third and Seventh Armies claimed well over 100,000 German prisoners in the victory.”[lxxvi] On the 22nd Third Army launched the 5th Infantry division across the Rhine at Nierstein and Oppenheim, surprising the Germans and beating Montgomery across the Rhine. Patton called Bradley: “Brad, for God’s sake tell the world we’re across…I want the world to know that Third Army made it before Monty.”[lxxvii] Weigley notes in this campaign “the American army’s sharpening instinct for the jugular,” and that it was a model “of not only how to gain ground of not only how to gain ground but to destroy enemy forces.”[lxxviii]

Plunder

9th Army and Allied Airborne forces participated in 21st Army Group’s grand set-piece crossing of the Rhine on 23 March. The attack had been prepared for weeks by Montgomery and more resembled an amphibious operation than a river crossing. The attack employed 25 divisions supported by 3,000 guns with maximum air support and naval amphibious units. Opposing the Army group were “five weak and exhausted German divisions”[lxxix] of 1st Parachute Army. The assault cost 9th Army thirty casualties. Montgomery also employed the American 17th and 6th British Airborne divisions in Operation Varsity which was the largest single day airborne operation of the war. Over 21,000 paratroops were dropped or air-landed in gliders into the face of heavy flak. Numerous troop transport planes and gliders were lost. The operation was of doubtful utility, ground forces were already well on their way to the objective the paratroops were landed on and the operation had a heavy cost, 17th Airborne took “some 1500 casualties, including 159 killed.” And 6th Airborne lost another 1400.[lxxx]

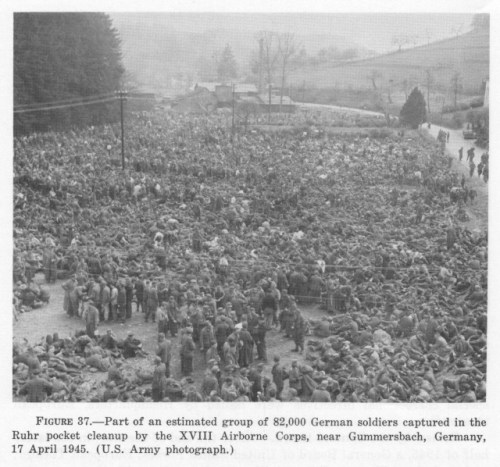

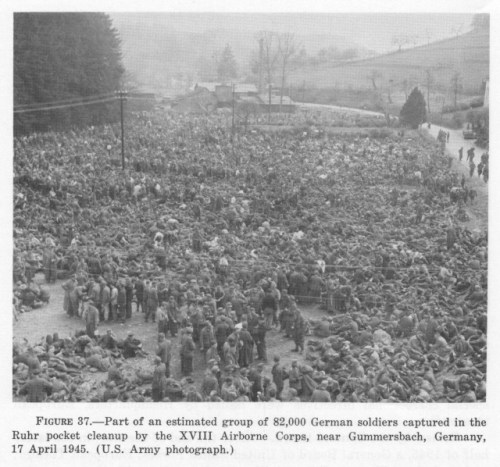

The Ruhr Pocket and the Decision to Stop on the Elbe

The last major operation in the West following the breakouts from the bridgeheads over the Rhine was the encirclement and reduction of the Ruhr pocket. This operation involved the 9th Army and 1st Army. The 3rd Army continued its operations east and south toward Nurnberg. Bradley, his blood stirred by the large numbers of prisoners taken in the Saar, Palatinate and Rhineland now became addicted by the completion of envelopments and he told his staff as “he shifted Hodges’ direction toward a meeting with Simpson encircling the Ruhr: “I’ve got bags on my mind.””[lxxxi] The Army Group completed the encirclement and reduced the pocket by April 18th. Two Army commanders, Von Zangen of 15th Army and Harpe of 5th Panzer Army as well as 25 other Generals and Admirals were caught in the American net. Vaunted formations such as Panzer Lehr and 116th Panzer were among the 317,000 German prisoners taken by the Army Group. XVII Corps alone captured 160,000 prisoners.[lxxxii] Field Marshal Model, the commander of Army Group B took his own life on the 21st. The one setback during the battle was during the spirited advance of the 3rd Armored division to Paderborn a task force ran into a Kampfgrüppe of King Tigers manned by Waffen SS Panzer training students stopped them with heavy losses.[lxxxiii] To make matters worse the 3rd Armored Division Commanding General, Maurice Rose was killed when his jeep encountered Tigers and a jittery German Panzertroop shot him when he removed his pistol attempting to surrender.[lxxxiv]

Despite the great number of prisoners taken and the elimination of the bulk of the Wehrmacht in the West the battle detracted from what had been hereto the overriding goal of the campaign, the capture of Berlin.[lxxxv] The reasons for this were twofold. At the Army Group level Bradley was determined to engage as many of his troops as possible so they would not be sucked into any offensive commanded by Montgomery who continued to clamor for control of American troops to make the final drive for Berlin. Eisenhower supported Bradley’s decision as he believed “that the Western Allies no longer had much chance of capturing “the main prize,” Berlin, anyway.”[lxxxvi] Weigley suggests that a better purpose for the troops that Bradley used to reduce the Ruhr pocket would have been to us them to aid 9th Army’s drive toward Berlin which was already closing on the Elbe. With the reuniting of the 1st and 9th Armies Bradley was poised to begin his drive to Berlin with the largest field command in American history.[lxxxvii]

US Vehicles Driving Towards Kassel

US Vehicles Driving Towards Kassel

The second reason was that Eisenhower had made a decision based on political and tactical considerations to shift the focus of the Allied effort from Berlin to Dresden and Leipzig yet not completely ruling out an advance toward Berlin.[lxxxviii] Attempts by 9th Army to drive toward Berlin were frustrated by unexpected German resistance to its bridgeheads over the Elbe. On the 15th of April Simpson flew to Bradley’s headquarters to propose an attack on Berlin. Bradley called Eisenhower who on hearing Bradley’s estimate of 100,000 casualties to take the city elected not to continue the attack towards Berlin.[lxxxix] Eisenhower had now concluded “that the National Redoubt was now over more importance than Berlin,”[xc] and directed Patton and Devers to secure it. Patton and Simpson were both incredulous at the decision and felt that it was “a terrible mistake.” Patton felt 9th Army could take Berlin in 48 hours.[xci] In a similar vein Patton’s move into Czechoslovakia was halted before Prague.

Overage German Recruits Captured by US Forces

Overage German Recruits Captured by US Forces

Eisenhower’s decision was political and tactical and was supported by the U.S. Chiefs of Staff;[xcii] Berlin would be in the Soviet zone even if he took it. Hastings sates the decision was “surely the correct one” noting that nothing could change the post-war settlement.[xciii] Murray and Millett agree.[xciv]Others such as J.F.C. Fuller felt that the political decisions had turned the fruits of victory “into the apples of Sodom, which turned to ashes as soon as they were plucked,”[xcv] leaving Eastern and Central Europe under the control of the Soviets. D’ Este notes that no matter what was decided that Eisenhower’s “hands were already tied by the agreement of the Big Three agreement over the division of occupied Germany.”[xcvi] In the end there may have been a political advantage to taking Berlin before the Soviets, but as Hastings notes: “It is hard to see how this could have been prevented, given the Western Allies sluggish conduct of the war.”[xcvii] This was the fault of both the British and Americans and this was in fact as much a part of the final settlement in Europe as any decision made in the final weeks of the war.

In retrospect one can see the historical consequences of Eisenhower’s decision, but how much that decision was influenced by the way the American Army’s organization and conduct for war is seldom mentioned. Perhaps had Eisenhower had the 200 plus divisions envisioned by the Victory plan, or had he been bolder and abandoned the broad front strategy inherited from Grant, history might be different today. There are always results. One should not devise strategies for the conduct of war that do not match up with the forces that you plan to employ. Organization, training and equipment must be designed for the type of war one intends to fight and are just as important as a grand strategy. This was the lesson of the American involvement in the European campaign. The American Army succeed in spite of the restraints that its leadership and saddled it with. The final campaign in Germany showed that at least parts of it had learned the hard lessons of war and could conduct a highly successful campaign.

Handshake on the Elbe: US and Red Army Troops Meeting

Handshake on the Elbe: US and Red Army Troops Meeting

[i] Weigley, Russell F.

Eisenhower’s Lieutenants: The Campaign in France and Germany 1944-1945. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 1981. p.2.

[ii] Ibid. p.728

[iii] Ibid. p.4.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] See Weigley’s article American Strategy, in Peter Paret’s Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Paret, Peter, editor. Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 1986 pp.434-436.

[vi] See Keene, Jennifer D. Doughboys, the Great War, and the Remaking of America. The John’s Hopkins University Press. Baltimore,MD. 2001. pp.42-44. Keene notes the results of the AEF’s training and Pershing’s organization and employment of the Army in WWI. The similarities to the American experience in WWII are startling. A comment of George Marshall after the war that: “Officers leading their men into battle, abandoned tactical maneuvering in favor of “steamroller operations” that forced men to keep going until exhaustion stopped them…” reminds one of the Huertgen Forrest. Likewise a similar situation arose in regard to training. Other comments are that the infantry was not well trained and that “many troops resisted advancing without artillery support….”

[vii] Herwig, Holger H. The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918. Arnold a Member of the Hodder Headline Group, London England 1998. p.424.

[viii] Millett, Allen R. and Maslowski, Peter. For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America. The Free Press, New York 1984. p.349.

[ix] Ibid. Weigley. p.25

[x] Matloff, Maurice Allied Strategy in Europe in Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Paret, Peter, editor. Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 1986 p.696.

[xi] Ibid. Weigley. p.5

[xii] Ibid. Weigley. p.23

[xiii] Ibid. p.728

[xiv] Mansoor, Peter R. The GI Offensive in Europe: The Triumph of American Infantry Divsions 1941-1945. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence KS. 1999 p.31.

[xv] Ibid. pp.253-254. Mansoor is the only historian that I have ever seen defend this system. Even Stephan Ambrose who generally leads the cheering section for the American Army in WWII condemned the system, which Mansoor admits in his account.

[xvi] Gabel, Christopher R. The Lorraine Campaign: An Overview September-December 1944. U.S. Army Command and Staff College, Ft. Leavenworth KS 1985. pp.34-35.

[xvii] Chaffee, Adna R. Mechanization in the Army, Statement to Congress, April 1941. p.19. Combined Arms Research Library, Digital Library http://cgsc.leavenworth.army.mil/carl/contentdm/home.htm

[xviii] Ibid. p.6.

[xix] _________Infantry in Battle 2nd Edition The Infantry Journal Incorporated, Washington DC 1939. p.68

[xx] See Chaffee and Infantry in Battle. Likewise this was echoed in S.L.A. Marshall’s book Armies on Wheels, William and Morrow Company, New York, NY 1941.

[xxi] Ibid. p.729.

[xxii] Ibid. p.14

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Ibid. p.662-663. Initially, 21,000 troops were taken from the COMMZ and 10,000 were directed to be transferred from the AAF. Additionally 2,253 black troops were formed into 37 platoons and distributed among the divisions of 12th and 6th Army Groups.

[xxv] Ibid. p.664. The efforts were successful and by April there was a surplus of 50,000 infantry soldiers beyond reported shortages, despite the fact that no more American or British divisions were available for deployment to the continent.

[xxvi] Ibid. Mansoor,

[xxvii] Ibid. Weigley. p.578

[xxviii] Hastings, Max. Armageddon: The Battle for Germany 1944-1945 Alfred A Knopf, New York NY 2004 p.340.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Ibid. Hastings. p.340

[xxxi] Ibid. p.341

[xxxii] Ibid. Weigley. p.583

[xxxiii] Bradley, Omar N. A Soldier’s Story Henry Holt and Company, New York NY 1951. p.501

[xxxiv] Ibid. Hastings. p.348

[xxxv] Ibid. Bradley. p.497

[xxxvi] Ibid. p.589.

[xxxvii] Ibid. Hastings. p.348.

[xxxviii] Patton, George S. War as I Knew It Originally published by Houghton Mifflin Company NY 1947, Bantam Paperback Edition, Bantam Books, New York, NY 1980 p.242

[xxxix] Ibid. Hastings. p.345

[xl] Ibid.

[xli] Ibid. Weigley. p.603

[xlii] Ibid. p.602

[xliii] Wilmont, Chester. The Struggle for Europe Harper and Brothers Publishers, New York, NY 1952 p.673

[xliv] Ibid. p.616

[xlv] Ibid. Hastings. p.365

[xlvi] Ibid. Weigley. p.621

[xlvii] Ibid.

[xlviii] Ibid. Bradley. p.509

[xlix] Ibid. Wilmont. p.674

[l] Ibid. Weigley. p.622.

[li] Ibid. 627

[lii] Ibid. Hastings. p.365

[liii] Ibid.

[liv] Murray, Williamson and Millett, Allan R. A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge Massachusetts and London England, 2000 p.478

[lv] Ibid. Mansoor. P.244.

[lvi] Ibid. Weigley. p.632

[lvii] D’Este, Carlo. Eisenhower: A Soldier’s Life Owl Books, Henry Holt and Company, New York NY 2002. p.681

[lviii] Ibid. p.682

[lix] Ibid. Bradley. p.511

[lx] Ibid. Weigley. p.629.

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Ibid. Wilmont. p.676

[lxiii] Liddell Hart, B.H. The History of the Second World War G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York NY 1970. p.678.

[lxiv] Ibid. Hastings. p.366.

[lxv] Newton, Steven H. Hitler’s Commander: Field Marshal Walter Model, Hitler’s Favorite General. DeCapo Press, Cambridge MA 2005. p.351.

[lxvi] Ibid. D’Este. Eisenhower p.682

[lxvii] Ibid. By this D’Este is obviously not referring to Bull and Eisenhower.

[lxviii] Ibid. Wilmont. p.677.

[lxix] Ibid. Liddell-Hart. p.677

[lxx] Warlimont, Walter. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters 1939-1945 translated by R.H. Barry. Presidio Press, San Francisco, CA 1964. p. 506.

[lxxi] Ibid. Weigly. p.635.

[lxxii] Ibid. p.638

[lxxiii] Ibid. Wilmont. p.678.

[lxxiv] Ibid.

[lxxv] D’Este, Carlo. Patton: A Genius for War. Harper Collins Publishers New York, 1995 p.711

[lxxvi] Ibid. Murray and Millet. p.479.

[lxxvii] Ibid. D’Este Eisenhower p.683

[lxxviii] Ibid. Weigley. p.639

[lxxix] Ibid. Liddell-Hart. p.678.

[lxxx] Ibid. Hastings. p.369.

[lxxxi] Ibid. Weigley. p.673.

[lxxxii] Ibid. p.680

[lxxxiii] Ibid. Hastings. p.377.

[lxxxiv] Ibid. p.675.

[lxxxv] Ibid. Weigley. p.674.

[lxxxvi] Ibid. p.684.

[lxxxvii] Ibid.

[lxxxviii] Ibid. p.688.

[lxxxix] Ibid. pp.698-699. Weigley believes that neither Eisenhower nor Bradley wanted to continue to Berlin; Bradley for the reason that Montgomery would steal the credit and Eisenhower because it was a “prestige objective” that would remain in the Soviet zone no matter who captured it.

[xc] Ibid. Wilmont. p.690.

[xci] Ibid. D’Este Patton. P.721

[xcii] Ryan, Cornelius. The Last Battle The Fawcett Popular Library, New York NY.1966. p.240.

[xciii] Ibid. Hastings. p.425

[xciv] Ibid. Murray and Millett. P.480

[xcv] Fuller, J.F.C. The Conduct of War 1789-1961 DaCapo Press edition, San Francisco, CA 1992. p.296.

[xcvi] Ibid. D’Este. Eisenhower. P.694.

[xcvii] Ibid. Hastings. p.512.

Bibliography

Bradley, Omar N. A Soldier’s Story Henry Holt and Company, New York NY 1951.

Chaffee, Adna R. Mechanization in the Army, Statement to Congress, April 1941. Combined Arms Research Library, Digital Library http://cgsc.leavenworth.army.mil/carl/contentdm/home.htm

D’Este, Carlo. Eisenhower: A Soldier’s Life Owl Books, Henry Holt and Company, New York NY 2002.

D’Este, Carlo. Patton: A Genius for War. Harper Collins Publishers New York, 1995

Fuller, J.F.C. The Conduct of War 1789-1961 DaCapo Press edition, San Francisco, CA 1992.

Gabel, Christopher R. The Lorraine Campaign: An Overview September-December 1944. U.S. Army Command and Staff College, Ft. Leavenworth KS 1985.

Hastings, Max. Armageddon: The Battle for Germany 1944-1945 Alfred A Knopf, New York NY

Herwig, Holger H. The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918. Arnold a Member of the Hodder Headline Group, London England 1998

Keene, Jennifer D. Doughboys, the Great War, and the Remaking of America. The John’s Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, MD. 2001.

Liddell Hart, B.H. The History of the Second World War G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York NY 1970

Mansoor, Peter R. The GI Offensive in Europe: The Triumph of American Infantry Divsions 1941-1945. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence KS. 1999

Millett, Allen R. and Maslowski, Peter. For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America. The Free Press, New York 1984

Murray, Williamson and Millett, Allan R. A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge Massachusetts and London England, 2000

Newton, Steven H. Hitler’s Commander: Field Marshal Walter Model, Hitler’s Favorite General. DeCapo Press, Cambridge MA 2005

Paret, Peter, editor. Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 1986

Patton, George S. War as I Knew It Originally published by Houghton Mifflin Company NY 1947, Bantam Paperback Edition, Bantam Books, New York, NY 1980

Ryan, Cornelius. The Last Battle The Fawcett Popular Library, New York NY.1966

Warlimont, Walter. Inside Hitler’s Headquarters 1939-1945 translated by R.H. Barry. Presidio Press, San Francisco, CA 1964

Weigley, Russell F. Eisenhower’s Lieutenants: The Campaign in France and Germany 1944-1945. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 1981.

Wilmont, Chester. The Struggle for Europe Harper and Brothers Publishers, New York, NY 1952

_________Infantry in Battle 2nd Edition The Infantry Journal Incorporated, Washington DC 1939

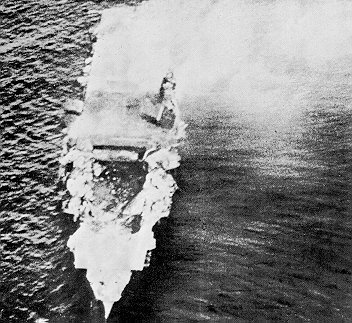

Lead aircraft ready to take off of IJN Carrier Akagi to attack Pearl Harbor beginning a 6 month chain of Japanese victories in the Pacific

Lead aircraft ready to take off of IJN Carrier Akagi to attack Pearl Harbor beginning a 6 month chain of Japanese victories in the Pacific US Destroyer USS Pope being blasted out of the water by Japanese Cruisers at the Battle of Java Sea

US Destroyer USS Pope being blasted out of the water by Japanese Cruisers at the Battle of Java Sea IJN Carrier Hiryu heavily damaged and abandoned at Midway. Hiryu, Akagi, Kaga and Soryu the creme of the Japanese carrier fleet were lost at Midway, the Japanese found it hard to replace them or their decimated air crews

IJN Carrier Hiryu heavily damaged and abandoned at Midway. Hiryu, Akagi, Kaga and Soryu the creme of the Japanese carrier fleet were lost at Midway, the Japanese found it hard to replace them or their decimated air crews Japanese destroyer shown sinking after being torpedoed by a US submarine

Japanese destroyer shown sinking after being torpedoed by a US submarine Aircraft like the F6F Hellcat drove Japanese aircraft such as the A6M2 Zero from the skies in the Pacific

Aircraft like the F6F Hellcat drove Japanese aircraft such as the A6M2 Zero from the skies in the Pacific Heavily fortified Japanese islands were either bypassed or taken in bloody assaults, here a 8″ gun on Tarawa

Heavily fortified Japanese islands were either bypassed or taken in bloody assaults, here a 8″ gun on Tarawa Japanese war industries were woefully ill equipped to match US war production. Here a factory producing Oscar fighter planes

Japanese war industries were woefully ill equipped to match US war production. Here a factory producing Oscar fighter planes The Carrier Taiho was the equivalent of the Essex Class but the Japanese could only produce one unit

The Carrier Taiho was the equivalent of the Essex Class but the Japanese could only produce one unit An Armada of US Essex Class Carriers in 1944 the Japanese could not keep pace with US Naval production

An Armada of US Essex Class Carriers in 1944 the Japanese could not keep pace with US Naval production The US Amphibious warfare capacity was a key factor in the ability of the United States to take the war to Japan

The US Amphibious warfare capacity was a key factor in the ability of the United States to take the war to Japan US Navy Submarines cut off Japan from its vital natural resources in Southeast Asia. A Sub Squadron above and USS Barb below

US Navy Submarines cut off Japan from its vital natural resources in Southeast Asia. A Sub Squadron above and USS Barb below B-29 Super-fortresses leveled Japanese cities and even excellent fighters like the Mitsubishi J2M Raiden could not stop them

B-29 Super-fortresses leveled Japanese cities and even excellent fighters like the Mitsubishi J2M Raiden could not stop them

Eisenhower and 101st Airborne

Eisenhower and 101st Airborne LST-325 at Normandy, Specialized Landing Ships and Craft were in High Demand and Short Supply in June 1944

LST-325 at Normandy, Specialized Landing Ships and Craft were in High Demand and Short Supply in June 1944 Omaha Beach

Omaha Beach Outnumbered Paratroops of II Fallschirmjaeger Corps Delayed US Forces Considerably in Normandy

Outnumbered Paratroops of II Fallschirmjaeger Corps Delayed US Forces Considerably in Normandy  8th Air Force Bombers Helped Hit German Oil Production Facilities and caused the Luftwaffe to spend its fighter squadrons over Germany than France

8th Air Force Bombers Helped Hit German Oil Production Facilities and caused the Luftwaffe to spend its fighter squadrons over Germany than France Landing craft passing USS Augusta

Landing craft passing USS Augusta Dual Drive or DD Tanks took heavy Losses at Omaha

Dual Drive or DD Tanks took heavy Losses at Omaha 1st Infantry Divison Troops at the Omaha Beach Sea Wall

1st Infantry Divison Troops at the Omaha Beach Sea Wall Panzers and Grenadiers in Normandy

Panzers and Grenadiers in Normandy

Tiger Tank and Crew in Normandy

Tiger Tank and Crew in Normandy Panzer Ace Captain Michael Wittmann on His Tiger Tank

Panzer Ace Captain Michael Wittmann on His Tiger Tank US Tanks and German Prisoners at St Lo

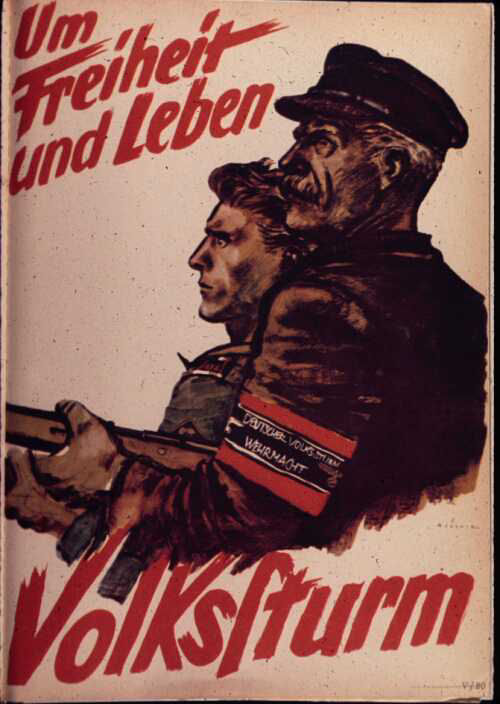

US Tanks and German Prisoners at St Lo Volksturm Members

Volksturm Members Volksturm receiving training on Panzerfaust Anti-Tank Rocket

Volksturm receiving training on Panzerfaust Anti-Tank Rocket Volksturm Propaganda Poster

Volksturm Propaganda Poster