Joshua Chamberlain Receives the Surrender of John Gordon at Appomattox

Friends of Padre Steve’s World,

One hundred and fifty four years ago on the 9th and 10th of April 1865, four men, Ulysses S Grant, Robert E. Lee, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Ely Parker, taught succeeding generations of Americans the value of mutual respect and reconciliation. The four men, each very different, would do so after a bitter and bloody war that had cost the lives of over 600,000 Americans which had left hundreds of thousands others maimed, shattered or without a place to live, and seen vast swaths of the country ravaged by war and its attendant plagues.

The differences in the men, their upbringing, and their views about life seemed to be insurmountable. The Confederate commander, General Robert E. Lee was the epitome of a Southern aristocrat and career army officer. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, like Lee was a West Point graduate and veteran of the War with Mexico, but there the similarities ended. Grant was an officer of humble means who had struggled with alcoholism and failed in his civilian life after he left the army, before returning to it as a volunteer when war began. Major General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain had been a professor of rhetoric and natural and revealed religion from Bowdoin College until 1862 when he volunteered to serve. He was a hero of Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg, who helped exemplify the importance of citizen soldiers in peace and war. Finally there was Colonel Ely Parker, a full-blooded Seneca Indian; a professional engineer by trade, a man who was barred from being an attorney because as a Native American he was never considered a citizen. Although he had been rejected from serving in the army for the same reason, his friend Grant had obtained him a commission and kept him on his staff.

General Ulysses S. Grant

A few days bef0ore the Confederate line around the fortress of Petersburg was shattered at the battle of Five Forks, and to save the last vestiges of his army Lee attempted to withdraw to the west. Within a few days the once magnificent Army of Northern Virginia was trapped near the town of Appomattox. On the morning of April 9th 1865 Lee replied to an entreaty of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant requesting that he and his Army of Northern Virginia be allowed to surrender. Lee wrote to Grant:

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA, APRIL 9, 1865

Lieut. Gen. U.S. GRANT:

I received your note of this morning on the picket-line, whither I had come to meet you and ascertain definitely what terms were embraced in your proposal of yesterday with reference to the surrender of this army. I now ask an interview in accordance with the offer contained in your letter of yesterday for that purpose.

R.E. LEE, General.

The once mighty Army of Northern Virginia, which had won so many victories, and which at its peak numbered nearly 80,000 men, was now a haggard and emaciated, but still proud force of about 15,000 soldiers. For Lee to continue the war now would mean that they would have to face hopeless odds against a vastly superior enemy. Grant recognized this and wrote Lee:

I am equally anxious for peace with yourself, and the whole North entertains the same feeling. The terms upon which peace can be had are well understood. By the South laying down their arms they will hasten that most desirable event, save thousands of human lives, and hundreds of millions of property not yet destroyed. Seriously hoping that all our difficulties may be set-tied without the loss of another life, I subscribe myself, &c.,

Since the high water mark at Gettysburg, Lee’s army had been on the defensive. Lee’s ill-fated offensive into Pennsylvania was one of the two climactic events that sealed the doom of the Confederacy. The other was Grant’s victory at Vicksburg which fell to him a day after Pickett’s Charge, and which cut the Confederacy in half.

General Robert E. Lee

The bloody defensive struggle lasted through 1864 as Grant bled the Confederates dry during the Overland Campaign, leading to the long siege of Petersburg. Likewise the armies of William Tecumseh Sherman had cut a swath through the Deep South and were moving toward Virginia from the Carolinas.

With each battle following Gettysburg the Army of Northern Virginia became weaker and finally after the nine month long siege of Petersburg ended with a Union victory there was little else to do. On the morning of April 9th a final attempt to break through the Union lines by John Gordon’s division was turned back by vastly superior Union forces.

On April 7th Grant wrote a letter to Lee, which began the process of ending the war in Virginia. He wrote:

General R. E. LEE:

The result of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the C. S. Army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.

U.S. GRANT, Lieutenant-General

Lee was hesitant to surrender knowing Grant’s reputation for insisting on unconditional surrender, terms that Lee could not accept. He replied to Grant:

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA, APRIL 7, 1865 Lieut. Gen. U.S. GRANT:

I have received your note of this date. Though not entertaining the opinion you express on the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia, I reciprocate your desire to avoid useless effusion of blood, and therefore, before considering your proposition, ask the terms you will offer on condition of its surrender.

R.E. LEE, General.

The correspondence continued over the next day even as the Confederates hoped to fight their way out of the trap that they were in. But now Robert E. Lee, who had through his efforts extended the war for at least six months, knew that he could no longer continue. Even so some of his younger subordinates wanted to continue the fight. When his artillery chief Porter Alexander recommended that the Army be released, “take to the woods and report to their state governors” Lee replied:

“We have simply now to face the fact that the Confederacy has failed. And as Christian men, Gen. Alexander, you & I have no right to think for one moment of our personal feelings or affairs. We must consider only the effect which our action will have upon the country at large.”

Lee continued:

“Already [the country] is demoralized by the four years of war. If I took your advice, the men would be without rations and under no control of their officers. They would be compelled to rob and steal in order to live…. We would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to recover from… You young fellows might go bushwhacking, but the only dignified course for me would be to go to General Grant and surrender myself and take the consequences of my acts.”

Alexander was so humbled at Lee’s reply he later wrote “I was so ashamed of having proposed such a foolish and wild cat scheme that I felt like begging him to forget he had ever heard it.” When Alexander saw the gracious terms of the surrender he was particularly impressed with how non-vindictive the terms were, especially in terms of parole and amnesty for the surrendered soldiers.

Abraham Lincoln had already set the tone for the surrender in his Second Inaugural Address given just over a month before the surrender of Lee’s army. Lincoln closed that speech with these words of reconciliation.

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

Lee met Grant at the house of Wilmer McLean, who had moved to Appomattox in 1861 after his home near Manassas had been used as a Confederate headquarters and was damaged by artillery fire. Lee was dressed in his finest uniform complete with sash, while Grant was dressed in a mud splattered uniform and overcoat only distinguished from his soldiers by the three stars on his should boards. Grant’s dress uniforms were far to the rear in the baggage trains and Grant was afraid that his slovenly appearance would insult Lee, but it did not. It was a friendly meeting, before getting down to business the two reminisced about the Mexican War.

Grant provided his vanquished foe very generous surrender terms:

“In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th inst., I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of N. Va. on the following terms, to wit: Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate. One copy to be given to an officer designated by me, the other to be retained by such officer or officers as you may designate. The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their commands. The arms, artillery and public property to be parked and stacked, and turned over to the officer appointed by me to receive them. This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done, each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.”

When Lee left the building Federal troops began cheering but Grant ordered them to stop. Grant felt a sense of melancholy and wrote “I felt…sad and depressed, at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people has fought.” He later noted: “The Confederates were now our countrymen, and we did not want to exult over their downfall.”

In the hours before and after the signing of the surrender documents old friends and classmates, separated by four long years of war gathered on the porch or around the house. Grant and others were gracious to their now defeated friends and the bitterness of war began to melt away. Some Union officers offered money to help their Confederate friends get through the coming months. It was an emotional reunion, especially for the former West Point classmates gathered there.

“It had never been in their hearts to hate the classmates they were fighting. Their lives and affections for one another had been indelibly framed and inextricably intertwined in their academy days. No adversity, war, killing, or political estrangement could undo that. Now, meeting together when the guns were quiet, they yearned to know that they would never hear their thunder or be ordered to take up arms against one another again.”

Grant also sent 25,000 rations to the starving Confederate army waiting to surrender. The gesture meant much to the defeated Confederate soldiers who had had little to eat ever since the retreat began.

The surrender itself was accomplished with a recognition that soldiers who have given the full measure of devotion can know when confronting a defeated enemy. Major General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, the heroic victor of Little Round Top was directed by Grant to receive the final surrender of the defeated Confederate infantry on the morning of April 12th.

It was a rainy and gloomy morning as the beaten Confederates marched to the surrender grounds. As the initial units under the command of John Gordon passed him, Chamberlain was moved with emotion he ordered his soldiers to salute the defeated enemy for whose cause he had no sympathy, Chamberlain honored the defeated Rebel army by bringing his division to present arms.

John Gordon, who was “riding with heavy spirit and downcast face,” looked up, surveyed the scene, wheeled about on his horse, and “with profound salutation returned the gesture by lowering his saber to the toe of his boot. The Georgian then ordered each following brigade to carry arms as they passed third brigade, “honor answering honor.”

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain

Chamberlain was not just a soldier, but before the war had been Professor of Natural and Revealed Religions at Bowdoin College, and a student of theology before the war. He could not help to see the significance of the occasion. He understood that some people would criticize him for saluting the surrendered enemy. However, Chamberlain, unlike others, understood the value of reconciliation. Chamberlain was a staunch abolitionist and Unionist who had nearly died on more than one occasion fighting the defeated Confederate Army, and he understood that no true peace could transpire unless the enemies became reconciled to one another.

He noted that his chief reason for doing so:

“The momentous meaning of this occasion impressed me deeply. I resolved to mark it by some token of recognition, which could be no other than a salute of arms. Well aware of the responsibility assumed, and of the criticisms that would follow, as the sequel proved, nothing of that kind could move me in the least. The act could be defended, if needful, by the suggestion that such a salute was not to the cause for which the flag of the Confederacy stood, but to its going down before the flag of the Union. My main reason, however, was one for which I sought no authority nor asked forgiveness. Before us in proud humiliation stood the embodiment of manhood: men whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster, nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve; standing before us now, thin, worn, and famished, but erect, and with eyes looking level into ours, waking memories that bound us together as no other bond;—was not such manhood to be welcomed back into a Union so tested and assured? Instructions had been given; and when the head of each division column comes opposite our group, our bugle sounds the signal and instantly our whole line from right to left, regiment by regiment in succession, gives the soldier’s salutation, from the “order arms” to the old “carry”—the marching salute. Gordon at the head of the column, riding with heavy spirit and downcast face, catches the sound of shifting arms, looks up, and, taking the meaning, wheels superbly, making with himself and his horse one uplifted figure, with profound salutation as he drops the point of his sword to the boot toe; then facing to his own command, gives word for his successive brigades to pass us with the same position of the manual,—honor answering honor. On our part not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer, nor word nor whisper of vain-glorying, nor motion of man standing again at the order, but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead!”

The next day Robert E Lee addressed his soldiers for the last time. Lee’s final order to his loyal troops was published the day after the surrender. It was a gracious letter of thanks to men that had served their beloved commander well in the course of the three years since he assumed command of them outside Richmond in 1862.

General Order

No. 9

After four years of arduous service marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.

I need not tell the survivors of so many hard fought battles, who have remained steadfast to the last, that I have consented to the result from no distrust of them.

But feeling that valour and devotion could accomplish nothing that could compensate for the loss that must have attended the continuance of the contest, I have determined to avoid the useless sacrifice of those whose past services have endeared them to their countrymen.

By the terms of the agreement, officers and men can return to their homes and remain until exchanged. You will take with you the satisfaction that proceeds from the consciousness of duty faithfully performed, and I earnestly pray that a merciful God will extend to you his blessing and protection.

With an unceasing admiration of your constancy and devotion to your Country, and a grateful remembrance of your kind and generous consideration for myself, I bid you an affectionate farewell. — R. E. Lee, General

The surrender was the beginning of the end. Other Confederate forces continued to resist for several weeks, but with the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia led by the man that nearly all Southerners saw as the embodiment of their nation the war was effectively over.

Lee had fought hard and after the war was still under the charge of treason, but he understood the significance of defeat and the necessity of moving forward as one nation. In August 1865 Lee wrote to the trustees of Washington College of which he was now President:

“I think it is the duty of every citizen, in the present condition of the Country, to do all in his power to aid the restoration of peace and harmony… It is particularly incumbent upon those charged with the instruction of the young to set them an example of submission to authority.”

Brigadier General Ely Parker

It is a lesson that all of us in our terribly divided land need to learn regardless of or political affiliation or ideology. After he had signed the surrender document, Lee learned that Grant’s Aide-de-Camp Colonel Ely Parker, was a full-blooded Seneca Indian. He stared at Parker’s dark features and said: “It is good to have one real American here.”

Parker, a man whose people had known the brutality of the white man, a man who was not considered a citizen and would never gain the right to vote, replied, “Sir, we are all Americans.” That afternoon Parker would receive a commission as a Brevet Brigadier General of Volunteers, making him the first Native American to hold that rank in the United States Army. He would later be made a Brigadier General in the Regular Army.

I don’t know what Lee thought of that. His reaction is not recorded and he never wrote about it after the war, but it might have been in some way led to Lee’s letter to the trustees of Washington College. I think with our land so divided, ands that is time again that we learn the lessons so evidenced in the actions and words of Ely Parker, Ulysses Grant, Robert E. Lee and Joshua Chamberlain, for we are all Americans.

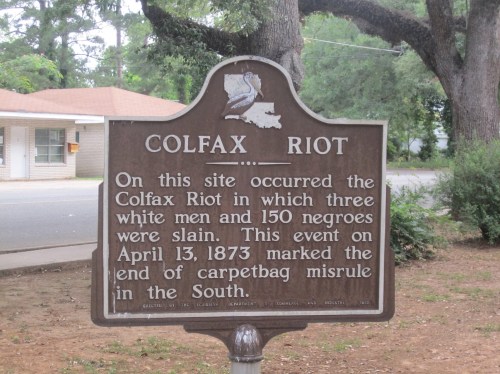

Sadly, I think that there is a portion of the American population who will not heed these words and will continue to agitate for policies and laws similar to those that led to the Civil War, and which those the could not reconcile defeat instituted again during the Post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras. For me such behavior and attitudes are incompressible, but they are all too real, and all too present in our divided nation.

But I still maintain hope that in spite of everything that divides us, in spite of the intolerance and hatred of some, that we can overcome. I think that the magnanimity of Grant in victory, the humility of Lee in defeat, the graciousness of Chamberlain in honoring the defeated foe, and the stark bluntness of Parker, the Native American, in reminding Lee, that “we are all Americans,” is something that is worth remembering, and yes, even emulating.

That is where we need to be in the age of President Trump. Robert E. Lee, could admit defeat, and though still at heart a racist, could still advocate for the end of a rebellion that he supported and reconciliation with a government which he had committed high treason against. Ulysses S. Grant and Joshua Chamberlain embodied the men of the Union who had fought for the Union, Emancipation, and against the Rebellion hat Lee supported to the end.

But even more so we need to remember the words of the only man whose DNA and genealogy did not make him a European transplant, the man who Lee refereed to as the only true American at Appomattox, General Ely Parker, the Native American who fought for a nation that not acknowledge him as a citizen until long after he was dead.

In the perverted, unrequited racist age of President Donald Trump we have to stop the bullshit, and take to heart the words of Ely Parker. “We are all Americans.” If we don’t get that there is no hope for our country. No amount of military or economic might can save us if we cannot understand Parker’s words, or the words of the Declaration: “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal…” Really, it does not matter if our relatives were second sons of European Gentry, religious dissidents, refugees of repressive regimes, African Slaves, Asians seeking a new life in a new country, or Mexican citizens who turned on their own country to become citizens of a new Republic, men like Mariano Vallejo, the Mexican governor of El Norte and one of the First U.S. Senators from California.

Let us never forget Ely Parker’ words at Appomattox, “We are all Americans.”

Sadly, there are not just more than a few Americans, and many with no familial or other connection to the Confederacy and the South than deeply held racism who would rather see another bloody civil war because they hate the equality of Blacks, Women, immigrants, and LGBTQ Americans more than they love the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States.

That is why Parker’s words to Lee still matter so much and why we must never give up the fight for equality for all Americans. Likewise, whether one likes it or not, Robert E. Lee broke his sacred oath to the Constitution as a commissioned officer refused to free the slaves entrusted to his care by his Father in Law in 1859, who refused to support his Confederate President’s plan to emancipate and free African American slaves who were willing to fight for the Confederacy until February 1865.

Lee the Myth is still greater than Lee the man in much of this country. Lee the man is responsible for the deaths for more Americans than the leaders of Imperial Germany, Imperial Japan, Nazi Germany, or any other foreign power. He even cast aside such loyalists as George Pickett, whose division he destroyed in a suicidal attack at Gettysburg on July 3rd 1863, and then continued to damn Pickett for mistakes which were his own until the end of the war.

Both sides of my family fought for the Confederacy as officers and members of the 8th Virginia Cavalry. Most reconciled, but others didn’t, including the patriarch of my paternal side of the family. His decision ended up costing the family millions of dollars in the following years. The maternal side was smart enough to reconcile after the war and to later engage in the profoundly libertarian practice of bootlegging until the end of prohibition. I don’t know if any members of either side of my family were Kan supporters, but if they were I wouldn’t doubt it. They lost what they had during the war by fighting on the wrong sided and refusing to reconcile with the United States, and they deserved it. Even Robert E. Lee refused to completely admit his crime of treason. He used the language of reconciliation without fully embracing it.

That my friends is the crime of those who today speak of freedom and reconciliation, but refused to apply it to themselves or their families. I guess that makes me different, and I’m okay I’m okay with that. I have to admit, that the person that I was in my early 20s, or the person that I am now could not have embraced secession or slavery. There is no moral reason that any Christian person could have fully embraced secession and civilly war to defend slavery, but people on both sides of my family did even as their neighbors embraced the Union.

So for me April 9th is very personal. I have served my country for nearly 38 years. I cannot abide men and women who treat the men and women that I have served with in the defense of this county as less than human or fully entitled to the rights that are mine, more to my birth and race than today than any of my inherent talents or abilities. That includes my ancestors who fought for the Confederacy on both sides of my family. Ancestors or not, they were traitors to everything that I believe in and hold dear.

As for me, principles and equality trump all forms of racism, racist ideology, and injustice, even when the President himself advocates for them. I am a Union man, despite my Southern ancestry, and I will support the rights of people my ancestors would never support, Blacks, Hispanics, Women, LTBTQ, and other racial, religious, or gender minorities. But then, I am a Unionist. I am a supporter of Equal rights for African Americans, I am a women’s rights advocate, including their reproductive rights, and I am a supporter of LGBTQ people and their rights, most of which are opposed by the Evangelical Christians who I grew up with. I also will not hesitate to criticize the elected President of the United States when he pisses on the preface of the Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution, attacks the bedrock principles of the Bill of Rights

How can I be silent?

Dietrich Bonhoeffer notes:

“The messengers of Jesus will be hated to the end of time. They will be blamed for all the division which rend cities and homes. Jesus and his disciples will be condemned on all sides for undermining family life, and for leading the nation astray; they will be called crazy fanatics and disturbers of the peace. The disciples will be sorely tempted to desert their Lord. But the end is also near, and they must hold on and persevere until it comes. Only he will be blessed who remains loyal to Jesus and his word until the end.”

Trump certainly hates those who hold fast to the worlds of Jesus. So I will stand fast on this anniversary of Appomattox and echoes the words of Eli Parker to President Trump himself: “Sir, we are all Americans.” He may not understand it, but I certainly do.

Until tomorrow,

Peace

Padre Steve+