A cohesive national strategy involves true debate and consideration of all available courses of action. It must look at the ends, ways and means of achieving national strategic objectives as well as the risk entailed in each course of action. It has to involve both the political leadership and military commanders. Clausewitz said: “the supreme, most far reaching act of judgment that the statesman and commander have to make is to establish by that test the kind of war on which they are embarking; neither mistaking it for, nor trying to turn it into, something that is alien to its nature.” [1]

“Wars are not free flowing events, sufficient unto themselves as objects for study and understanding. Instead they are entirely the product of their contexts.” [2] Thus it is imperative that both political and military leaders understand for what purpose they embark on a war or begin a campaign. Even in the recent American experience we can recount time after time where American political leaders of both the Republican and Democrat parties, as well as military leaders and planners have failed to grasp the central truth of was Clausewitz wrote about the nature of war.

British political and military theorist Colin S. Gray writes: “Choice of strategy can determine whether or not policy goals will be attainable. And that choice must provide the most vital contexts for tactical behavior. Once policy objectives have been chosen, strategy is the function that delivers victory.” [3] In our recent wars and in the American Civil War this maxim has been born out time and time again.

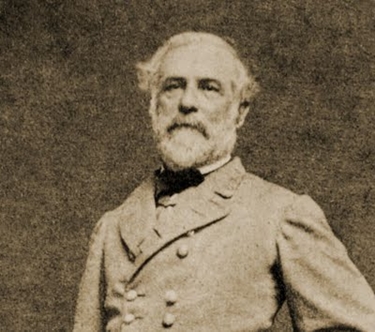

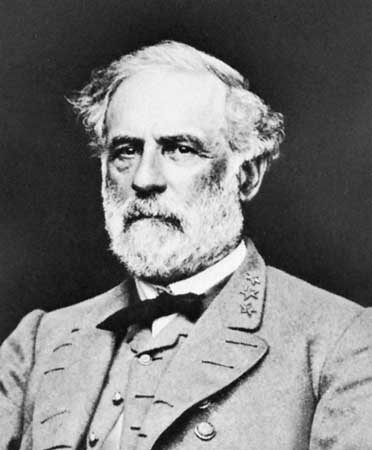

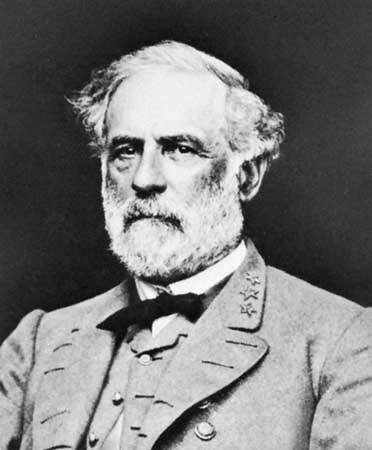

Thus, the Gettysburg campaign has to be looked at in the context of Grand Strategy and what was necessary for both sides to achieve their goals. For the Confederacy this was independence and in the context of the Gettysburg campaign the key question is whether it should have been made at all. While Lee is regarded as a masterful commander by many, the myth created by the Lost Cause school of history, in which the failure of Confederate war aims cannot be ascribed to Lee, keeps many people from asking the hard questions of strategy, and how Lee as commander failed to understand what was best for his country.

The key consideration, as Alan T. Nolan observes “must be whether a general’s actions helped or hurt the cause of his government in view of that government’s grand strategy. In short, the appropriate inquiry is to ask whether a general’s actions related positively or negatively to the war objectives and national policy of his government.” [4] The question was one of following a strategy of the defensive as Washington had done in the Revolutionary War, or a strategy of the offense culminating in a climactic battle that would decide the outcome of the war.

A defensive strategy was seen by British observers early in the war as the most feasibly for achieving Southern military and political goals in relationship to attaining independence. In the Revolution, Washington remained on the “grand strategic defensive” and “lost many battles and retreated many times, but they kept their forces in the field to avoid being ultimately defeated, and they won because the British decided that the struggle was either too hopeless or too burdensome to pursue.” [5] They had no doubt that this was the best policy for the Confederate government and military to achieve their strategic end.

The terrain of Virginia, particularly the number of east-west running rivers, the swamps that lay to the east of Richmond and the nearly impassible Wilderness to its north made any Union offensive a costly proposition. Clausewitz noted that terrain has “a decisive influence on the engagement, both as to its course and to its planning and exploitation….Their principle effect lies in the realm of tactics, but the outcome is a matter of strategy” [6]

This naturally advantageous terrain gave the advantage to Lee on the defense, but Lee seemed to never fully appreciate the strategic strength that the nature of the terrain, especially that of the Wilderness offered him. J.F.C. Fuller noted that “the Wilderness had been his staunchest ally. It was not only a natural fortress protecting Richmond, but a spider’s web to any army advancing from the north. Lee never fully realized this, for if he had done so his strategy would have been based upon maneuvering his enemy again and again into this entanglement and defeating him.” [7]

However, the strategic defensive was not that of Robert E. Lee. Lee’s view throughout the war, even as late as the siege of Petersburg was that of the offensive and climactic battle: “If we can defeat or drive the armies of the enemy from the field, we shall have peace. Our efforts and energies should be devoted to that object.” [8]

In 1863 the Confederacy was confronted with the choice of how it would deal with the multiple threats to it posed by Union forces in both the West at Vicksburg, as well as in Tennessee as well as the East, where the Army of the Potomac was in striking distance of Richmond. The strategic situation was bad but few Confederate politicians realized just how bad things were, or cared in the post Chancellorsville euphoria.

In the west the strategic river city of Vicksburg Mississippi was threatened by the Army of Union General Ulysses S Grant, and Naval forces under the command of Admiral David Farragut and Admiral David Dixon Porter. If Vicksburg fell the Union would control the entire Mississippi and cut the Confederacy in two. Union forces also maintained a strong presence in the areas of the Virginia Tidewater and the coastal areas of the Carolinas; while in Tennessee a Union Army under Rosecrans, was stalemated, but still threatening Chattanooga, the gateway to the Deep South. The blockade of the United States Navy continually reinforced since its establishment in 1861, had crippled the already tenuous economy of the Confederacy. The once mocked “anaconda strategy” devised by General Winfield Scott was beginning to pay dividends. [9] Of the nine major Confederate ports linked by rail to the inland cities the Union, all except three; Mobile, Wilmington and Charleston were in Union hands by April 1862. [10]

However, the Confederate response to the danger was “divided councils and paralysis” [11] in their upper leadership, between those like Lee who advocated for the offensive and those like Davis who advocated a defensive strategy. The military relationship between Lee and Davis “represented a continuous compromise between the president’s undeclared policy of outlasting the enemy and the general’s purpose of winning by breaking the enemy’s will to continue their effort at subjugation.” [12]

Davis, though he was Commander-in-Chief wavered between the two strategic ideas throughout the first years of the war, something that was worse than coming to no decision at all. Lee’s latest biographer Michael Korda makes the point that: “The danger that the Confederacy might unravel from west to east, whatever happened between the Rappahannock and the Potomac, was Grant’s central strategic idea, and should have been the overriding concern of the Confederate government; but Lee’s position as the South’s most respected and admired military figure, the high drama of his rapid marches and his victories against much larger armies had a profound effect on southern military strategy.” [13] Instead it was not, and a fog of confused policies confounded Confederate war efforts.

Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon and President Jefferson Davis recognized the danger in the winter of 1862-1863. During the winter Davis and Seddon suggested to Lee that he detach significant units, including Pickett’s division to relieve the pressure in the west and blunt Grant’s advance. Lee would have nothing of it; he argued that the war would be won in the East. He told Seddon that “The adoption of your proposition is hazardous, and it becomes a question between Virginia and the Mississippi.” [14] From a strategic point of view it is hard to believe that Lee could not see this, “but in the post-Chancellorsville aura of invincibility, anything seemed possible.” [15]

However, much of Lee’s reasoning can be explained by what he saw as his first duty, the defense of Virginia. Lee’s biographer Michael Korda points out that Lee’s strategic argument was very much influenced by his love of Virginia, which remained his first love, despite his deep commitment to the Confederacy. Korda noted that Lee: “could never overcome a certain myopia about his native state. He remained a Virginian first and foremost…..” [16] Fuller wrote that Lee “was so obsessed by the idea of threatening Washington in order to relieve Northern Virginia, that throughout his generalship he never saw the war as a whole.” [17] It was Lee’s view that if Virginia was lost, so was the Confederacy, and was concerned that whatever units left behind should he dispatch troops from his Army west, would be unable to defend Richmond.

Likewise, despite the success of his defensive battles at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, Lee was not encouraged. Those victories had elated the Confederacy and caused great concern in the North. But Lee was depressed after each. Lee told Harry Heth after Chancellorsville: “Our people were wild with delight- I, on the contrary, was more depressed than after Fredericksburg; our loss was severe, and again we had not gained an inch of ground, and the enemy could not be pursued…” [18]

Some Confederate leaders realized the mortal danger presented by Grant in the West including officials in the War Department, one of whom wrote “The crisis there is of the greatest moment. The loss of Vicksburg and the Mississippi river…would wound us very deeply in a political as well as a military point of view.” [19]

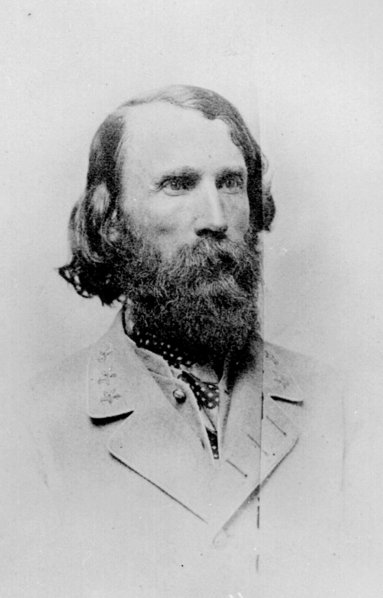

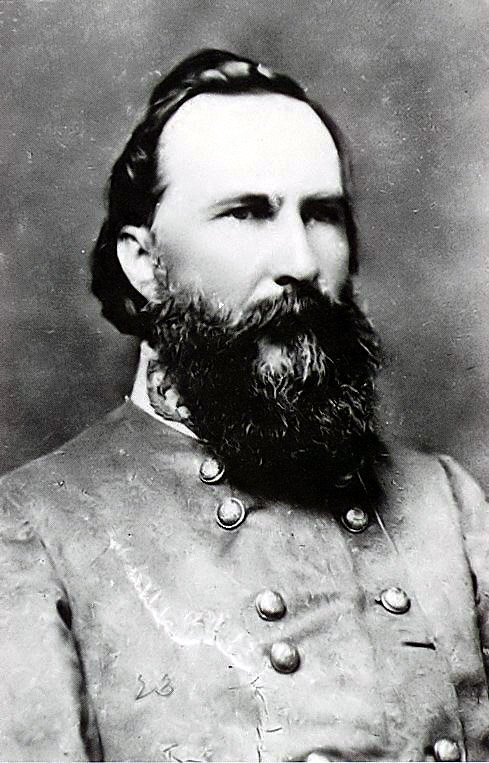

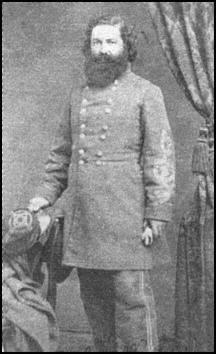

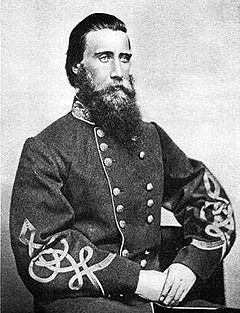

Despite this Seddon did remain in favor of shifting troops west and relieving Vicksburg. He was backed in this by Joseph Johnston, Braxton Bragg, P.T.G. Beauregard and James Longstreet. In Mid-May of 1863 Beauregard proposed a strategy to concentrate all available forces in in Tennessee and going to the strategic defensive on all other fronts. Beauregard, probably the best Southern strategist “saw clearly that the decisive point lay in the West and not the East.” [20] Beauregard’s plan was to mass Confederate forces was crush Rosecrans, relieve Vicksburg and then move east to assist Lee in destroying the Army of the Potomac in his words to complete “the terrible lesson the enemy has just had at Chancellorsville.” [21] His plan was never acknowledged and in a letter to Johnston, where he re-sent the plan he noted “I hope everything will turn out well, although I do not exactly see how.” [22]

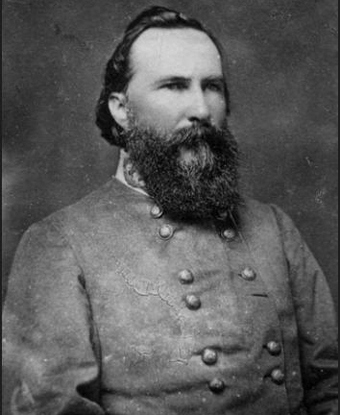

James Longstreet had proposed a similar measure to Seddon in February 1863 and then again on May 6th in Richmond. Longstreet believed that “the Confederacy’s greatest opportunity lay “in the skillful use of our interior lines.” [23] He suggested to Seddon that two of his divisions link up with Johnston and Bragg and defeat Rosecrans and upon doing that move toward Cincinnati. Longstreet argued that since Grant would have the only Union troops that could stop such a threat that it would relieve “Pemberton at Vicksburg.” [24] Seddon favored Longstreet’s proposal but Jefferson Davis having sought Lee’s counsel rejected the plan, Longstreet in a comment critical of Davis’s rejection of the proposal wrote: “But foreign intervention was the ruling idea with the President, and he preferred that as the easiest solution of all problems.” [25] Following that meeting Longstreet pitched the idea to Lee who according to Longstreet “recognized the suggestion as of good combination, and giving strong assurance of success, but he was averse to having a part of his army so far beyond his reach.” [26]

In early May 1863 Lee, commanding the Army of Northern Virginia realized that the Confederacy was in desperate straits. Despite numerous victories against heavy odds, Lee knew that time was running out. Though he had beaten the Army of the Potomac under General Joseph Hooker at Chancellorsville, he had not destroyed it and Hooker’s Army, along with a smaller force commanded by General Dix in Hampton Roads still threatened Richmond. He had rejected the western option presented by Seddon, Beauregard and Longstreet. Lee questioned “whether additional troops there would redress the balance in favor of the Confederacy, and he wondered how he would be able to cope with the powerful Army of the Potomac.” [27]

In Lee’s defense neither of these suggestions was unsound, but his alternative, an offensive into Pennsylvania just as unsound and undertaken for “confused” reasons. Confederate leaders realized that “something had to be done to save Vicksburg; something had to be done to prevent Hooker from recrossing the Rappahannock; something had to be done to win European recognition, or compel the North to consider terms of peace…” [28] However added to these reasons, and perhaps the most overarching for Lee was “to free the State of Virginia, for a time at least, from the presence of the enemy” and “to transfer the theater of war to Northern soil….” [29]

On May 14th Lee travelled by train to Richmond to meet with President Jefferson Davis and War Secretary James Seddon. At the meeting Lee argued for an offensive campaign in the east, to take the war to Pennsylvania. Lee had three major goals for the offensive, two which were directly related to the immediate military situation and one which went to the broader strategic situation.

Lee had long believed that an offensive into the North was necessary, even before Chancellorsville. As already noted, Lee did not believe that reinforcing the Confederate Armies in the West would provide any real relief for Vicksburg. Lee believed, quite falsely, that the harsh climate alone would force Grant to break off his siege of Vicksburg. [30] Russell Weigley wrote that “In truth, Lee seems to have been less than fully responsive to the problems of the West, partly out of Virginia parochialism- he always regarded his sword as serving his first state of Virginia-and partly in adherence to his military philosophy,” [31] that of the offensive. Lee was not willing to sacrifice Virginia for the west, and “tenaciously fought every suggestion that the Army of Northern Virginia be denuded to reinforce the west, and his influence over Davis guaranteed, at least until the fall of 1863, that the defense of Virginia would always be able to outweigh the demands for help from the Confederate forces in the West.” [32]

Instead of sending troops west, Lee believed that his army, flush with victory needed to be reinforced and allowed to advance into Pennsylvania. Lee proposed withdrawing Beauregard’s 16,000 soldiers from the Carolinas to the north in order “increase the known anxiety of Washington authorities” [33] and he sought the return of four veteran brigades which had been loaned to D.H. Hill in North Carolina. In this he was unsuccessful. He received two relatively untested brigades from Hill; those of Johnston Pettigrew and Joseph Davis instead two of Pickett’s veteran brigades. The issue of the lack of reinforcements was a “commentary on the severe manpower strains rending the Confederacy…and Davis wrote Lee on May 31st, “and sorely regret that I cannot give you the means which would make it quite safe to attempt all that we desire.” [34]

Lee’s Chief of Staff Colonel Charles Marshall crafted a series of courses of action for Lee designed to present the invasion option as the only feasible alternative for the Confederacy. Lee’s presentation was an “either or” proposal. He gave short shrift to any possibility of reinforcing Vicksburg and explained “to my mind, it resolved itself into a choice of one of two things: either to retire to Richmond and stand a siege, which must ultimately end in surrender, or to invade Pennsylvania.” [35] As any military planner knows the presentation of courses of action designed to lead listeners to the course of action that a commander prefers by ignoring the risks of such action, downplaying other courses of action is disingenuous. In effect Lee was asking Davis and his cabinet to “choose between certain defeat and possibly victory” [36] while blatantly ignoring other courses of action or playing down other very real threats in the West.

Lee embraced the offensive as his grand strategy and rejected the defensive in his presentation to the Confederate cabinet, and they were “awed” by Lee’s strategic vision. Swept up in Lee’s presentation the cabinet approved the invasion despite the fact that “most of the arguments he made to win its approval were more opportunistic than real.” [37] However, Postmaster General John Reagan objected and stated his dissent arguing that Vicksburg had to be the top priority. But Lee was persuasive telling the cabinet “There were never such men in any army before….They will go anywhere and do anything if properly led….” So great was the prestige of Lee, “whose fame…now filled the world,” that he carried the day.” [38]

Although both Seddon and Davis had reservations about the plan they agreed to it. Unfortunately for all of them they never really settled the important goals of the campaign including how extensive the invasion would be, how many troops would he need and where he would get them. [39] The confusion about these issues was fully demonstrated by Davis in his letter of May 31st where he “had never fairly comprehended” Lee’s “views and purposes” until he received a letter and dispatch from the general that day.” [40] That lack of understanding is surprising since Lee had made several personal visits to Davis and the cabinet during May and demonstrates again the severe lack of understanding of the strategic problems by Confederate leaders.

Lee believed that his offensive would relieve Grant’s pressure on Pemberton’s Army at Vicksburg. How it would do so is not clear since the Union had other armies and troops throughout the east to parry any thrust made had the Army of the Potomac endured a decisive defeat that not only drove it from the battlefield but destroyed it as a fighting force. Postmaster General Reagan believed that the only way to stop Grant was “destroy him” and “move against him with all possible reinforcements.” [41]

Likewise Lee believed that if he was successful in battle and defeated the Army of the Potomac in Pennsylvania that it could give the peace party in the North to bring pressure on the Lincoln Administration to end the war. This too was a misguided belief and Lee would come to understand that as his forces entered Maryland and Pennsylvania where there was no popular support for his invading army. The fact was that those that “though there was a strong peace party in the North, they did not realize that Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had settled once and for all the question of foreign intervention, and second that to invade the North would consolidate the Federals instead of dividing them.” [42]

In the meeting with the cabinet, Postmaster-General Reagan, agreed with General Beauregard and warned that “the probability that the threatened danger to Washington would arouse again the whole of the Yankee nation to renewed efforts for the protection of their capital.” [43] Reagan was decidedly against Lee’s offensive. He “saw everything wrong with Lee’s plan and everything right with the plan it had superseded. Grant was the main threat to the survival of the Confederacy, and it was Grant at whom the main blow must be aimed and struck.” [44] But “Lee’s opinion carried so much weight that Davis felt compelled to concur” [45] with Lee and voted with the remaining cabinet members to allow the offensive.

Stephens the fire breathing Vice President “wanted to negotiate for peace, and he foresaw rightly that Lee’s offensive would strengthen and not weaken the war party in the North….Stephens was strongly of the opinion that Lee should have remained on the defensive and detached a strong force to assist Johnston against Grant at Vicksburg.” [46] However, he was kept in the dark as to Lee’s plans until after Lee had crossed the Potomac.

Likewise, Lee, the consummate defender of Virginia was determined to at least for a season remove the war from his beloved state. He believed that if he could spend a summer campaign season in the North, living off of Union foodstuffs and shipping booty back to the Confederacy that it would give farmers in Northern Virginia a season to harvest crops unimpeded by major military operations.

While the offensive did give a few months relief to these farmers it did not deliver them. Likewise Lee’s argument that he could not feed his army flies in the face of later actions where for the next two years the Army of Northern Virginia continued to subsist. Alan Nolan noted that if a raid for forage was a goal of the operation then “a raid by small, mobile forces rather than the entire army would have had considerably more promise and less risk.” [47] D. H. Hill in North Carolina wrote his wife: “Genl. Lee is venturing upon a very hazardous movement…and one that must be fruitless, if not disastrous.” [48]

Though Lee won permission to invade Pennsylvania, he did not get all that he desired. Lee wanted, and believed that he would have his entire army to conduct his offensive. However, Davis did not understand or conceive that Lee’s offensive scheme was a “change in the existing policy, a shift from the defense to the offense. To Davis, Lee’s invasion was merely a necessary expedient in the policy of static, scattered defensiveness.” [49]

Davis refused Lee reinforcements from the coastal Carolinas, and “had not the slightest intention of reducing a single garrison to support Lee’s offensive.” [50] Davis insisted on units being left to cover Richmond in case General Dix advanced on Richmond from Hampton Roads. Much of this was due to political pressure as well as the personal animus of General D. H. Hill who commanded Confederate forces in the Carolinas towards Lee. The units included two of Pickett’s brigades which would be sorely missed on July third in the doomed effort to break the Union center on Cemetery Ridge. As a result Lee was without a significant portion of his army when he moved north. Lee did not learn “until he had crossed the Potomac that four of his best brigades, the equivalent of a division, were to be uselessly employed away from the army.” [51]

Lee’s decision revealed an unresolved issue in Confederate Grand Strategy, the conflict between the strategy of the offensive and that of the defensive. Many in the Confederacy realized that the only hope for success was to fight a defensive campaign that made Union victory so expensive that eventually Lincoln’s government would fall or be forced to negotiate.

The conflict between those who believed in the offensive like Lee, and those that advocated a strategic defensive strategy resulted in indecision, which resulted in a policy that brought about “the worst of both worlds.” [52] The fact that Lee got permission to invade but was denied significant numbers of experienced troops as well as support from other departments meant that “what Lee designed as a total stroke from a concentration of its armed strength, was reduced to a desperate, unsupported gamble of one man with one army-and not all of that.” [53] Knowing this, Lee still chose to continue his offensive, something that along with his “own awareness of factors that argued against it.” [54]

Lee was convinced that ultimate victory could only be achieved by decisively defeating and destroying Federal military might in the East. His letters are full of references to crush, defeat or destroy Union forces opposing him. His strategy of the offensive was demonstrated on numerous occasions in 1862 and early 1863, however in the long term, the strategy of the offensive was unfeasible and “counterproductive in terms of the Confederacy’s “objects of war.” [55]

Lee’s offensive operations always cost his Army dearly in the one commodity that the South could not replace, nor keep pace with its Northern adversary, his men. His realism about that subject was shown after he began his offensive when he wrote Davis about how time was not on the side of the Confederacy. He wrote: “We should not therefore conceal from ourselves that our resources in men are constantly diminishing, and the disproportion in this respect…is steadily augmenting.” [56] Despite this, as well as knowing that in every offensive engagement, even in victory he was losing more men percentage wise than his opponent Lee persisted in the belief of the offensive.

When Lee fought defensive actions on ground of his choosing, like at Fredericksburg, he was not only successful but husbanded his strength. However, when he went on the offensive in almost every case he lost between 15 and 22 percent of his strength, a far higher percentage in every case than his Union opponents. In these battles the percentage of soldiers that he lost was always more than his Federal counterparts, even when his army inflicted greater aggregate casualties on his opponents. Those victories may have won Lee “a towering reputation” but these victories “proved fleeting when measured against their dangerous diminution of southern white manpower.” [57] Lee recognized this in his correspondence but he did not alter his strategy of the offensive until after his defeat at Gettysburg.

The course of action was decided upon, but one has to ask if Lee’s decision was wise decision at a strategic level, not simply the operational or tactical level where many Civil War students are comfortable. General Longstreet’s artillery commander, Colonel Porter Alexander described the appropriate strategy of the South well, he wrote:

“When the South entered upon war with a power so immensely her superior in men & money, & all the wealth of modern resources in machinery and the transportation appliances by land & sea, she could entertain but one single hope of final success. That was, that the desperation of her resistance would finally exact from her adversary such a price in blood & treasure as to exhaust the enthusiasm of its population for the objects of the war. We could not hope to conquer her. Our one chance was to wear her out.” [58]

What Alexander describes is the same type of strategy successfully employed by Washington and his more able officers during the American Revolution, Wellington’s campaign on the Iberian Peninsula against Napoleon’s armies, and that of General Giap against the French and Americans in Vietnam. It was not a strategy that completely avoided offensive actions, but saved them for the right moment when victory could be obtained.

It is my belief that Lee erred in invading the North for the simple fact that the risks far outweighed the possible benefits. As Russell Weigley noted “for a belligerent with the limited manpower resources of the Confederacy, General Lee’s dedication to an offensive strategy was at best questionable.” [59] The offensive was a long shot for victory at best, and Lee was a gambler, audacious possibly to a fault. His decision to go north exhibited a certain amount of hubris as he did not believe that his army could be beaten, even when it was outnumbered. Lee had to know from experience that even in victory “the Gettysburg campaign was bound to result in heavy Confederate casualties…limit his army’s capacity to maneuver…and to increase the risk of his being driven into a siege in the Richmond defenses.” [60] The fact that the campaign did exactly that demonstrates both the unsoundness of the campaign and is ironic, for Lee had repeatedly said in the lead up to the offensive in his meetings with Davis, Seddon and the cabinet that “a siege would be fatal to his army” [61] and “which must ultimately end in surrender.” [62]

Grand-strategy and national policy objectives must be the ultimate guide for operational decisions. “The art of employing military forces is obtaining the objects of war, to support the national policy of the government that raises the military forces.” [63] Using such criteria, despite his many victories Lee has to be judged as a failure as a military commander.

Lee knew from his previous experience that his army would suffer heavy casualties. Lee also understood that a victory over the Army of the Potomac deep in Northern territory could cost him dearly. He knew the effect that a costly victory would have on his operations, but he still took the risk. That decision was short sighted and diametrically opposed to the strategy that the South needed to pursue in order to gain its independence. Of course some will disagree, but I am comfortable in my assertion that it was a mistake that greatly affected the Confederacy’s only real means of securing its independence, the breaking of the will of the Union by making victory so costly that it would not be worth the cost.

In light of all of these factors one has to ask a question that is applicable as much today as it was to Lee. Since the object of a campaign is to be able to connect national strategy to the operational and tactical objectives of any campaign, in other words the connection of the campaign to grand-strategy objectives of a nation. In the case of the Confederacy it was to achieve independence, and as Clausewitz so keenly noted that “the political object, which was the original motive, must become an essential factor in the equation.” [64] The Gettysburg campaign, “Lee’s most audacious act, is the apogee of his grand strategy of the offensive.” But the question that has to be asked is “whether Lee should have been there at all.” [65] The same question should be asked by any political or military leader before embarking on a war or campaign within the war.

Notes

[1] Clausewitz, Carl von. On WarIndexed edition, edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1976 p.88

[2] Gray, Colin S. Fighting Talk: Forty Maxims on War, Peace, and Strategy Potomac Book, Dulles VA 2009 p.3

[3] Ibid. Gray Fighting Talk p.54

[4] Nolan, Alan T. Robert E. Lee: A Flawed General in Major Problems in American Military History: Documents and Essays Edited by Chambers, John Whiteclay II and Piehler, G. Kurt Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York 1999 p.175

[5] Nolan, Alan T. R. E. Lee and July 1 at Gettysburg in the First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.9

[6] Clausewitz, Carl von. On WarIndexed edition, edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1976 p.348

[7] Fuller, J.F.C Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship Indiana University Press, Bloomington Indiana, 1957 p.192

[8] Ibid. NolanR. E. Lee and July 1 at Gettysburg in the First Day at Gettysburg p.5

[9] Fuller, J.F.C. The Conduct of War 1789-1961 Da Capo Press, New York 1992. Originally published by Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick N.J p.101 Fuller has a good discussion of the Anaconda strategy which I discussed in the chapter: Gettysburg, Vicksburg and the Campaign of 1863: The Relationship between Strategy, Operational Art and the DIME

[10] Ibid. Fuller The Conduct of War 1789-1961 p.101

[11] McPherson, James. The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1988 p.629

[12] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 pp.20-21

[13] Korda, Michael. Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2014 pp.524-525

[14] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.34

[15] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.647

[16] Korda, Michael. Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2014 p.525

[17] Ibid. Fuller, J.F.C Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship p.193

[18] Guelzo Allen C. Fateful Lightening: A New History of the Civil War Era and Reconstruction Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2012 p.339

[19] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.5

[20] Ibid. Fuller, J.F.C Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship p.193

[21] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.429

[22] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.429

[23] Ibid. Korda Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee p.525

[24] Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 1993 p.241

[25] Longstreet, James From Manassas to Appomattox, Memoirs of the Civil War in America originally published 1896, Amazon Kindle Edition location 4656

[26] Ibid. Longstreet, James From Manassas to Appomattox, Memoirs of the Civil War in America location 4705

[27] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.5

[28] Ibid. Fuller Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and p.194

[29] Taylor, Walter. General Lee: His campaigns in Virginia 1861-1865 With Personal Reminiscences University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln Nebraska and London, 1994 previously published 1906 p.180.

[30] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.430

[31] Weigley, Russell F. The American Way of War: A History of United States Military History and Policy University of Indiana Press, Bloomington IN, 1973 pp.114-115

[32] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening: A New History of the Civil War Era and Reconstruction p.340

[33] Ibid. Korda Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee p.528

[34] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.51

[35] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.431

[36] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.431

[37] Tredeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.6

[38] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.647

[39] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.7

[40] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.7

[41] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.432

[42] Fuller, J.F.C. Decisive Battles of the U.S.A. 1776-1918 University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln 2007 copyright 1942 The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals p.222

[43] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.432

[44] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.432

[45] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.647

[46] Ibid. Fuller Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and p.194

[47] Ibid. NolanR. E. Lee and July 1 at Gettysburgin the First Day at Gettysburg p.2

[48] Ibid. Sears. Gettysburg p.51

[49] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.27

[50] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.27

[51] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.36

[52] Ibid. Weigley The American Way of War p.118

[53] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.28

[54] Ibid. Nolan Robert E. Lee: A Flawed General p.176

[55] Ibid. Nolan Robert E. Lee: A Flawed General in Major Problems p.176

[56] Taylor, John M. Duty Faithfully Performed: Robert E Lee and His CriticsBrassey’s, Dulles VA 1999 p.134

[57] Gallagher, Gary W. The Confederate War: How Popular Will, Nationalism and Military Strategy Could not Stave Off Defeat Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London 1999 p.120

[58] Alexander, Edward Porter. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander, ed. Gary W. Gallagher, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill NC, 1989 p.415

[59] Ibid. Weigley The American Way of War p.118

[60] Ibid. NolanR. E. Lee and July 1 at Gettysburg in the First Day at Gettysburg p.11

[61] Ibid. NolanR. E. Lee and July 1 at Gettysburg in the First Day at Gettysburg p.11

[62] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian p.431

[63] Ibid. NolanR. E. Lee and July 1 at Gettysburg in the First Day at Gettysburg p.4

[64] Ibid. Clausewitz On War pp.80-81

[65] Ibid. NolanR. E. Lee and July 1 at Gettysburg in the First Day at Gettysburg p.10