Friends of Padre Steve’s World

A bit of a break from the past few days of confronting the civil rights issues and racism at work in the aftermath of the Emmanuel A.M.E. church massacre. I’m sure that I will be doing more to follow that up in the near future, but it looks like the most prominent symbol of the ideological and sometimes religious hatred that has been at the heart of American racism since the Civil War is beginning to come down, even in the South as people finally begin to face up to the evil for which that flag stood.

This is another part of my Civil War and Gettysburg text on the formation of the armies that fought the Civil War.

When one thinks of our all-volunteer force today it is hard to imagine forming armies of this size and scope around such small regular forces. The story of how North and South raised their armies, and the stories of the volunteers of the first part of the war is amazing. I hope that you enjoy.

Peace

Padre Steve+

The Secession Crisis, Mobilization, and Volunteer Armies

The American Civil War was the first American war fought by massed armies of mobilized citizens. All previous wars had been fought by small numbers of Regular Army troops supported by various numbers of mobilized State Militia formations or volunteer formations raised for the particular war; “The fighting force of the 1860s was a conglomerate of diverse units, each with its own degree of importance, pride, proficiency, and jealousy. Whether of North or South, an army began as little more than a loosely organized mob actuated by more enthusiasm than by experience. Its composition ran the full gauntlet of humankind.” [1]

In 1860 the Regular Army numbered 16,000 troops at the beginning of the war. These included some 1105 officers, and were organized into “ten regiments of infantry, four of artillery, and five of cavalry (including dragoons and mounted riflemen)” [2] These regiments were broken up into small units and they and their soldiers were scattered about in far flung isolated posts around the country and in the new western territories. The units primarily fought Indians and performed what best could be described as constabulary duties. Others, mostly from artillery units manned the coastal defense fortifications that protected American’s key ports and entrances to key waterways along the eastern seaboard. Even so, after the War with Mexico “three quarters army’s artillery had been scrapped” and most of the army’s artillerymen and their units were “made to serve as infantry or cavalry, thus destroying almost completely their efficacy as artillery.” [3]

The secession crisis and the outbreak of the war fractured the army, particularly the officer corps. The officer corps was heavily Southern and many Northern officers had some sympathy with their Southern brothers in arms. It has to be said that of the men holding positions of high command from 1849 to 1861 that many were Southerners:

“all of the secretaries of war were Southerners, as were the general in chief, two of the three brigadier generals, all but one of the army’s geographical departments on the eve of the Civil War, the authors of the two manuals on infantry tactics, and the artillery manual used at West Point, and the professor who taught tactics and strategy at the military academy.” [4]

Most of the Army remained loyal to the Union, “except for 313 officers who resigned their commissions.” [5] Those who remained loyal to the Union included the General in Chief, Winfield Scott, as well as the professor who had taught so many of those now leaving to serve the Confederacy, Dennis Hart Mahan. However, of the others brigadier generals William Harney, David Twiggs and Joseph E. Johnston, Brevet Brigadier General Albert Sidney Johnston, and the army’s Adjutant General, Colonel Samuel Cooper, and the newly promoted Colonel Robert E. Lee all went south. “Even so, 40 to 50 per cent of the Southern West Point graduates on active duty in 1860 held to their posts and remained loyal to the Union.” [6]

A Political Backlash against West Point and the Officer Corps

The exodus of these officers created a backlash against West Point and the professional officers who remained in service of the Union, especially those who were Democrats and to radical Republicans were soft on slavery. Some Republican members of Congress including Senator Ben Wade of Ohio, “figured that political apostasy had been taught at West Point as well, and he didn’t know which sin was worse – it or treason.” [7] The fact that the leaders of the Union forces defeated at Bull run were West Point graduates added incompetence to the list of the crimes, real and imagined committed by the officers of the Regular Army. When Congress reconvened in 1861 Wade said:

“I cannot help thinking…that there is something wrong with this whole institution. I do not believe that in the history of the world you can find so many men who have proved themselves utterly faithless to their oaths, ungrateful to the Government that supported them, guilty of treason and a deliberate intention to overthrow that Government which educated them and given them support, as have emanated from this institution…I believe from the idleness of these military educated gentlemen this great treason was hatched.” [8]

Wade did not mention in his blanket his condemnation of the “traitors” that many “West Pointers from the Southern States – 162 of them – had withstood the pull of birth and kin to remain with the Union.” [9]

Wade’s fellow radical Senator Zachariah Chandler of Michigan urged Congress to dissolve the Military Academy. The academy, he said “has produced more traitors within the last fifty years than all the institutions of learning and education that have existed since Judas Iscariot’s time.” [10] Despite the words and accusations of the radical fire-eaters like Wade and Chandler and other like them, more level headed men prevailed and reminded the nation that there had been many other traitors. Senator James Nesmith of Oregon said: “Treason was hatched and incubated at these very decks around me.” [11]

Politicians and Professionals: Building Volunteer Armies

Many of the officers who left the army to serve the Confederacy were among the Army’s best and brightest, and many of them later rose to prominence and fame in their service to the Confederacy. In contrast to the officers who remained loyal to the Union, those that many in Congress despised and “pushed aside and passed over” in favor of “officers called back into service or directly appointed from civil life, the “South welcomed its professionals and capitalized on their talents. Sixty-four per cent of the Regular Army officers who went South became generals; less than 30 per cent of those who stayed with the Union achieved that rank.” [12]

The Union had a small Regular Army, which did undergo a significant expansion during the war, and the Confederacy did not even have that. During the war the “Confederacy established a regular army that attained an authorized strength of 15,000” [13] but few men ever enlisted in it. This was in large part due to the same distrust of the central government in Richmond that had been exhibited to Washington before the war.

Thus both sides fell back on the British tradition of calling up volunteers. The British had “invented volunteer system during the Napoleonic Wars, also to save themselves from the expense of permanent expansions of their army, and the United States had taken over the example in the Mexican War…” [14] The volunteer system was different from the militias which were completely under the control of their State and only given to the service of the national government for very limited amounts of time. The volunteers were makeshift organizations operating in a place somewhere between the Regular Army and the State militias and like the British system they saved “Congress the expense of permanently commissioning officers and mustering men into a dramatically expanded Federal service.” [15] As such the volunteer regiments that were raised by the States “were recruited by the states, marched under state-appointed officers carrying their state flag as well as the Stars and Stripes.” [16]

President Lincoln’s call for volunteers appealed “to all loyal citizens to favor, facilitate and aid this effort to maintain the honor, the integrity, and the existence of our Northern Union, and the perpetuity of the popular government; and to redress the wrongs already long enough endured.” [17] The Boston Herald proclaimed “In order to preserve this glorious heritage, vouchsafed to us by the fathers of the Republic, it is essential that every man perform his whole duty in a crisis like the present.” [18] The legislature of the State of Mississippi sated its arguments a bit differently and asserted, “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest in the world.” Texas explained that it had joined the Union “as a commonwealth holding, maintaining and protecting the institution known as negro slavery – the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits.” [19] A newspaper correspondent wrote:

“All, all of every name and every age to arms! To arms! My father go, my son go, my brother go, your country calls you.” He called out to Southern women as well, “mothers, wives and daughters buckle on the armor of loved ones, the correspondent urged, “bid them with Roman fairness, advance and never return until victory perches on their banner.” [20]

Those who went off to war left their homes and families. Young Rhode Island volunteer Robert Hunt Rhodes wrote that is mother told him “in the spirit worth of a Spartan mother of old said: “My son, other mothers must make sacrifices and why should not I?” [21] The bulk of the soldiers that enlisted on both sides in 1861 were single their median age “was twenty-four. Only one in seven enlistees that first year was eighteen or younger, and fewer than a third were twenty-one or younger.” [22]

Illustrious regiments such as the 1st Minnesota Volunteers, the 20th Maine Volunteers, the 69th New York Volunteer Infantry, and the African American 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry were just a few of the many regiments mustered into Union service under this system. As the war went on and the initial regiments were decimated by losses in combat and to disease, Northern governors “preferred to organize new regiments rather than to replenish old ones whittled down by battle and sickness. Fresh units swelled a state’s contributions, and the provided governors an opportunity to win more political favors by appointing more regimental officers.” [23] This practice produced “an army of shadow units” as “it was up to the regimental commanding officer to keep up a supply of new enlistments from back home for his own regiment, but most commanders could ill afford to detail their precious supply of junior officers for recruiting duty behind the lines.” [24]

Even before secession many Southern states began to prepare for war by building up their militias, both in numbers as well as by sending agents to arms suppliers in the North, as was done by Georgia Governor Joseph E. Brown who “sent an official north to purchase arms, ammunition and accouterments.” [25] After the bombardment of Fort Sumter both sides raced to build up their militaries. Jefferson Davis, the new President of the Confederacy who was a West Point graduate and former Secretary of War called for volunteers. On March 6th 1861 the new Provisional Confederate Congress in Montgomery authorized Davis to “call out the militia for six months and to accept 100,000 twelve-month volunteers.” [26] Within weeks they had passed additional legislation allowing for the calling up of volunteers for six months, twelve months and long-term volunteers up to any length of time. “Virginia’s troops were mustered en masse on July 1, 1861, by which time the state had 41,885 volunteers on its payroll.” [27]

With the legislation in hand Davis rapidly called up over 60,000 troops to the Confederate Cause, and this was before Virginia and North Carolina seceded from the Union. A mixture of former Regular Army officers commanded these men, most of whom occupied the senior leadership positions in the army, volunteer officers, made up the bulk of the Confederate officer corps. “Well over 700 former students at Virginia Military Institute served as officers in the war, most in the Virginia Theater….” [28]Among these men was Robert Rodes who became one of Robert E. Lee’s finest division commanders.

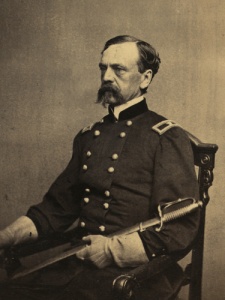

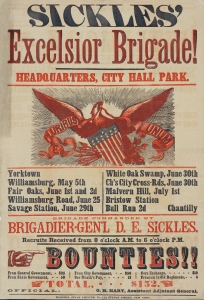

In the North Abraham Lincoln was in a quandary. Congress was out of session, so relying on the Militia Act of 1795 called out 75,000 three-month militiamen to support the Union cause. The legislatures of the Northern States so well that the over-recruited and in this first call up the government “accepted 9,816 men, but governors clamored for the War Department to take still more troops.” [29] Dan Sickles, a rather infamous Democrat politician was one of these men. Sickles had been a Democratic Congressman representing the district of New York City that was in the control of Tammany Hall. In 1859 Sickles stood trial for the murder of Barton Key, the District Attorney for Washington D.C. and the nephew of Francis Scott Key. Key had been conducting an affair with Sickles’ young wife Maria and in a fit of anger Sickles confronted Key, who had been spotted attempting a liaison with Maria and shot him dead near Lafayette Square and the White House. Sickles was acquitted on the basis of temporary insanity becoming the first man in the United States to have that distinction.

The ambitious Sickles, “almost overnight, using flag-waving oratory, organizational skills, and promissory notes, had his regiment, the 70th New York Volunteers, well in hand.” [30] Not content with a regiment and knowing that a brigade would bring him his star as a brigadier general, he quickly the Excelsior Brigade in New York.

Major General Dan Sickles

Within weeks Sickles had raised over 3000 men, a full forty companies and the New York Newspapers praised Sickles’ efforts. But partisan politics was at play. To Governor Edward Morgan, the fact that a Tammany Hall Democrat “was getting too far out ahead in the state’s race to supply manpower to the endangered Union” [31] was embarrassing and the Governor ordered Sickles to “disband all but eight of his forty companies.” [32] The incredulous, yet ambitious Sickles, knowing that Lincoln needed Democratic support to prosecute the war, traveled to Washington where after seeking an audience with the President. Lincoln was hesitant to infringe on any governor’s control of state units, but he was loath to lose the services of any soldiers. Lincoln discussed the matter with Secretary of War Simon Cameron and they ordered that Sickles “keep his men together until they could be inducted by United States officers.” [33] That process took two moths but in July Sickles was able to have the brigade sworn into service as a brigade of United States Volunteers.

For Sickles and most officers, volunteer and regular alike a regiment was a large military formation Likewise, a brigade massive and for most of these men divisions and corps on the scale of those found in Europe were almost unthinkable, but war was changing and this would be the scope of the coming war.

More troops were needed and with Congress out of session, President Lincoln acted “without legal authority…and increased the Regular Army by 22,714 men and the Navy by 18,000 and called for 42,034 three-year volunteers.” [34] On July 4th 1861 Lincoln “asked sanction for his extralegal action and for authority to raise at least another 400,000 three-year volunteers.” [35] Congress approved both of the President’s requests, retroactively, and in fact, “greatly expanded the numbers of volunteer recruitments, up to a million men – nothing more than the 1795 statute authorized either of these follow-up calls, and Lincoln would later have to justify his actions on the admittedly rather vague basis of the “war powers of the government.” [36]

In the North “the war department was staggered by the task of finding competent officers for an already numbering nearly half a million.” [37] There were so few professional officers available to either side that vast numbers of volunteer officers of often dubious character and ability were appointed to command the large number of volunteer regiments and brigades which were being rapidly mustered into service. Within months of the secession crisis the Regular Army of the United States, minus the officers who resigned to serve the Confederacy, “was swamped by a Union war army that reached about 500,000 within four months of the firing on Fort Sumter.” [38]

The Regular Army officers who remained loyal to the Union as well as those who left the army and joined the newly formed Confederacy were joined by a host of volunteer officers. Some of these officers, men like Ulysses Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, George McClellan, Braxton Bragg, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Jubal Early, and many others had left the army for any number of reasons only to return to the colors of the Union or the Confederacy during the secession crisis or at the outbreak of the war. Some of these men like George Sears Greene and Isaac Trimble Many were West Point graduates who had left the army decades before the war and almost to a man “nearly all of them displayed an old regular’s distrust of any general who had risen by political means.” [39] The hold of West Point and the teachings of Dennis Hart Mahan regarding professionalism had left a lasting imprint on these men.

Another issue faced by all of the officers now commanding large formations in the Civil War was their inexperience in dealing with such large numbers of troops. When the war began, the officers educated at West Point, as well as others who had been directly appointed had previously only commanded small units. Even regimental commanders such as Joseph Johnston, Albert Sidney Johnston, and Robert E. Lee seldom had more than a few companies of their regiments with them at any given time for any given operation. Likewise, the men who had campaigned and fought in Mexico who had some experience in handling larger formations had for the most part left the service. The senior officers who had served in Mexico and that remained on active duty were handicapped because the Mexican war was still very much a limited Napoleonic War fought with Napoleonic era weapons against a more numerous but poorly equipped and trained enemy.

Other volunteer officers had little or no military experience or training and owed their appointments as officers to their political connections, business acumen or their ability to raise troops. It was not atypical for a volunteer officer to gain his rank and appointment based on the number of that he brought into the army, “if he recruited a regiment he became a colonel, while if he brought in a brigade he was rewarded with the shining star of a brigadier general.” [40] This led to a type of general “appointed for their political influence or – at least in the North with its more heterogeneous population – their leadership of ethnic groups.” [41] Despite the dangers of their inexperience, both Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis had to appoint such men in order to maintain political support for the war.

Some of these men proved disastrous as commanders and their ineptness cost many lives. Henry Wager Halleck, wrote “It seems but little better than murder to give important commands to such men as Banks, Butler, McClernand, Sigel, and Lew Wallace…yet it seems impossible to prevent it.” [42] That being said some of the volunteer politically appointed generals proved to be exceptional learners of the art of war and impressive commanders in the own right.

Among the officers appointed for political considerations by Abraham Lincoln were the prominent Democratic politicians “Benjamin F. Butler, Daniel E. Sickles, John A. McClernand, John A. Logan.” [43] Among those commissioned to enlist immigrant support were Major General Carl Schurz and Brigadier General Alexander Schimmelpfennig who helped mobilize German immigrants to the Union cause. Both men were refugees from the failed revolution of 1848. Likewise, Brigadier General Thomas Francis Meagher, a survivor of the 1848 revolt in Ireland, who had escaped imprisonment in Australia helped to recruit and then commanded the famous Irish Brigade, whose regiments of Irish immigrants marched under the colors of the United States and the Green flag with the Harp of Erin.

The Irish and the German soldiers volunteered in large part because they saw the Union as the hope of their people that had given them refuge from tyranny in Europe. The Irish, under the religious, political and economic thumb of Britain fled to the United States, many the victims of famine. The Irish were not sympathetic as a whole to the plight of slave and many sympathized with the South, their desire to save the Union was greater and they volunteered in overwhelming numbers. One Irish Sergeant wrote his family in Ireland who did not understand why he fought for the Union:

“Destroy this republic and her hopes are blasted If Irland is ever ever [sic] free the means to accomplish it must come from the shore of America…When we are fighting for America we are fighting for the intrest of Irland striking a double blow cutting with a two edged sword For while we strike in defense of the rights of Irishmen here we are striking a blow at Irlands enemy and oppressor England hates this country because of its growing power and greatness She hates it for its republican liberty and she hates it because Irishmen have a home and government here and a voice in the counsels of the nation that is growing stronger every day which bodes no good for her.” [44]

Thus for many Irishmen fighting for the Union had a twofold purpose, seeing the war as Americans as well as Irishmen, they were fighting for Ireland as much as they were fighting for the Union. Some too believed that the war would be a training ground for Irishmen who would someday return home to drive the English from their homeland. Thomas Meagher the commander of the Irish Brigade explained,

“It is a moral certainty that many of our countrymen who enlist in this struggle for the maintenance of the Union will fall in the contest. But, even so; I hold that if only one in ten of us come back when this war is over, the military experience gained by that one will be of more service in the fight for Ireland’s freedom than would that of the entire ten as they are now.” [45]

Many Germans and others were driven from their homeland in the wake of the failed revolutions of 1848. Having been long under autocratic and oligarchic rule in the old country many of the German, Polish and other volunteers who fled after the failed revolutions of 1848 “felt that not only was the safety of the great Republic, the home of their exiled race, at stake, but also the great principle of democracy were at issue with the aristocratic doctrines of monarchism. Should the latter prevail, there was no longer any hope for the struggling nationalities of the Old World.” [46] These immigrant soldiers saw the preservation of the Union in a profoundly universal way, as the last hope of the oppressed everywhere. Eventually the Germans became “the most numerous foreign nationality in the Union armies. Some 200,000 of them wore the blue. The 9th Wisconsin was an all-German regiment. The 46th New York was one of ten Empire State units almost totally German in makeup.” [47]

In the North a parallel system “composed of three kinds of military organizations” developed as calls for “militia, volunteers and an expanded regular army” went out. [48] A number of regular army officers were allowed to command State regiments or brigades formed of State units, but this was the exception rather than the rule. One of these men was John Gibbon who commanded the legendary Iron Brigade at the beginning of its existence through its first year of combat.

In the South too men without little or no military training and experience raised companies and regiments for the Confederate cause. Like Lincoln Jefferson Davis had to satisfy political faction as well as some prominent politicians aspirations for military glory. Thus Davis “named such men as Robert A. Toombs of Georgia and John B. Floyd and Henry A. Wise of Virginia as generals.” [49] These men were not alone; many more politicians would receive appointments from Davis and the Confederate Congress.

Some of these men were gifted in recruiting but were sadly deficient as commanders. Men like John Brockenbrough and Edward O’Neal were capable of raising troops but in combat proved to be so inept that they got their men slaughtered and were removed from the army of Northern Virginia by Robert E. Lee. But others including South Carolina’s Wade Hampton, Georgia’s John Gordon and Virginia’s William “Little Billy” Mahone, none of who had any appreciable military experience proved to be among the best division commanders in Lee’s army. By 1864 Gordon was serving as an acting Corps commander and Hampton had succeeded the legendary J.E.B. Stuart as commander of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Lower ranking officers in the regiments formed by the states on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line, were most often elected by their units. During the war, some of these lower ranking officers rapidly progressed up the ranks and rose to command regiments and brigades, mostly due to their natural leadership abilities. That being said the volunteer system in which units elected their officers often to be fraught with problems. “Officers who might be popular as good fellows but who knew neither how to give orders and to get them obeyed nor even what kind of orders to give….At his worst, the volunteer officer could be as fully ignorant and irresponsible as the men he was supposed to command.” [50] Such officers proved to be a source of repeated concern for the professional officers who served alongside them.

John Reynolds, fresh from his assignment as Commandant of Cadets at West Point noted of the Pennsylvania volunteers that he commanded, “They do not any of them, officers or men, seem to have the least idea of the solemn duty they have imposed on themselves in becoming soldiers. Soldiers they are not in any sense of the word.” [51] In time both the Federal and Confederate armies instituted systems of qualifying exams for commissioned officers in order to weed out the worst of the incompetent officers.

Given the limitations of the volunteer officers who made up the bulk of the men commanding companies, battalions and regiments, “for the average soldier was that drill became his training for the realities of actual battlefield fighting.” This was helpful in getting “large and unwieldy bodies of men to the battlefield itself, but it generally turned out to be useless one the shooting started, especially as units lost cohesion and started to take casualties.” [52] This was much in evidence on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg when Brigadier General Joseph Davis’s untested brigade got caught in the Railroad Cut and was decimated by Union troops.

These men, the regulars and the volunteers, were now faced with the task of organizing, training and employing large armies made up primarily of militia units and volunteers. Most had little experience commanding such units and their experience with militia and volunteer formations during the Mexican War did not increase the appreciation of Regulars for them or for their leaders. J.F.C Fuller noted that at the beginning of the war “the Federal soldier was semiregular and the Confederate semiguerilla. The one strove after discipline, the other unleashed initiative. In battle the Confederate fought like a berserker, but out of battle he ceased to be a soldier.” [53] Both required certain kinds of leadership and Regular officers serving in both the Union and Confederate armies “embedded with the volunteers to give them some professional stiffening privately regarded them as uncontrollable adolescents who kicked off every back-home restraint the moment they were on campaign.” [54] Over the course of time this did change as the units of both armies learned to be professional soldiers.

At the beginning of the war General George McClellan successful fought the break-up of the Regular United States Army, “which some argued should be split up to train volunteer brigades” [55] as had his predecessor General Winfield Scott. He and Scott helped keep it separate from the militia units organized by the States, “keeping it intact as the nucleus of an expandable army.” [56] This preserved a professional core in a time where the new volunteer units were learning their craft, but McClellan did approve of a measure to have regular officers command some of the new volunteer brigades.

Regular Army units were formed for the duration of the war and were exclusively under the control of the Federal government. While comparatively few in number, they often held the line and kept the Army of the Potomac intact during some early battles where volunteer units collapsed. Volunteer regiments, often officered by regulars or former regulars “remained state-based, and they signed up for two- or three- year periods, after which they returned to civilian life and their evaporated without any further fiscal obligations.” [57] Some of the volunteer regiments were formed from various state militia units, but since few states had effective militia systems, militia units “were usually employed only on emergency rear-echelon duties, to free up the volunteers and regulars.” [58]

The Confederacy faced a similar situation to the Union, but it did not have a Regular Army and all of its units were raised by the various states. “In early 1861 the Confederate Congress authorized the creation of a provisional army of 100,000 men. To get these troops [the first Confederate Secretary of War Leroy Pope] Walker asked state governors to raise regiments and transfer them to the national army. The War Office provided generals and staff officers and, in theory at least, could employ the troops and their officers in any way it pleased once they mustered the provisional army.” [59] Some states were quite cooperative but others were not and the tension between the central government in Richmond in regard to military policy and some states would continue throughout the war. The quality of these units varied widely, mostly based on the leadership provided by their officers. That being said, many of the regiments mustered into service early in the war proved tough and resilient serving with distinction throughout the war.

Like the Federal forces, Southern units were officered by a collection of professionals from the ante-bellum Army, militia officers, political appointees or anyone with enough money to raise a unit. However command of divisional sized units and above was nearly always reserved to former professional soldiers from the old Army, most being graduates of West Point. At Gettysburg only one officer commanding a division or above in the Army of Northern Virginia was a non-academy graduate. This was the young and dashing Robert Rodes, who was a graduate of VMI. The quality of these officers varied greatly, as some of the old regulars failed miserably in combat and some of the volunteers such as John Gordon were remarkably successful as leaders of troops in combat.

As in the North, Southern militia and home guard units remained to free up the volunteer regiments and brigades fighting with the field armies. However, due to the South was always wrestling with the intense independence of every state government, each of which often held back units from service with the field armies in order to ensure their own states’ defense.

The withholding of troops and manpower by the states hindered Confederate war efforts, even though “the draft had been “eminently successful” in Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina, but less so in Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida.” [60] In the latter states, especially Georgia some Confederate Governors used militia appointments to protect men from the draft, classifying them as key civil servants in defiance of the needs of Richmond and the field armies for troops to fight the war.

The Changing Character of the Armies and Society: From All-Volunteer to Conscription: The Beginning of the Draft

Gettysburg was the last battle where the original volunteer armies predominated as the nature of both armies was changed by the war. Initially both sides sought to fight the war with volunteers but the increasingly costly battles which consumed vast numbers of men necessitated conscription and the creation of draft laws and bureaus.

The in April 1862 Confederate Congress passed the Conscription Act of 1862 which stated that “all persons residing in the Confederate States, between the ages of 18 and 35 years, and rightfully subject to military duty, shall be held to be in the military service of the Confederate States, and that a plain and simple method be adopted for their prompt enrollment and organization.” [61] The act was highly controversial, often resisted and the Confederate Congress issued a large number of class exemptions. Despite the exemptions “many Southerners resisted the draft or assisted evasion by others” [62] The main purpose of the conscription act was “to stimulate volunteering rather than by its actual use” [63] and while it did help increase the number of soldiers in Confederate service by the end of 1862 it was decidedly unpopular among soldiers, chafing at an exemption for “owners or overseers of twenty or more slaves” [64] who referred to the war as a “rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight.” [65]

Some governors who espoused state’s rights viewpoints “utilized their state forces to challenge Richmond’s centralized authority, hindering efficient manpower mobilization.” [66] Some, most notably Georgia’s governor Joseph Brown “denounced the draft as “a most dangerous usurpation by Congress of the rights of the States…at war with all principles for which Georgia entered the revolution.” [67] Governor Brown and a number of other governors, including Zebulon Vance of North Carolina fought the law in the courts but when overruled resisted it through the many exemption loopholes, especially that which they could grant to civil servants.

In Georgia, Governor Brown “insisted that militia officers were included in this category, and proceeded to appoint hundreds of new officers.” [68] Due to the problems with the Conscription Act of 1862 and the abuses by the governors, Jefferson Davis lobbied Congress to pass the Conscription Act of 1864. This act was designed to correct problems related to exemptions and “severely limited the number of draft exemption categories and expanded military age limits from eighteen to forty-five and seventeen to fifty. The most significant feature of the new act, however, was the vast prerogatives it gave to the President and War Department to control the South’s labor pool.” [69] Despite these problems the Confederacy eventually “mobilized 75 to 80 percent of its available draft age military population.” [70]

The Congress of the United States authorized conscription in 1863 as the Union Army had reached an impasse as in terms of the vast number of men motivated to serve “for patriotic reasons or peer group pressure were already in the army” while “War weariness and the grim realities of army life discouraged further volunteering” and “the booming war economy had shrunk the number of unemployed men to the vanishing point.” [71] Like the Confederate legislation it was also tremendously unpopular and ridden with exemptions and abuses. The Federal draft was conducted by lottery in each congressional district with each district being assigned a quota to meet by the War Department. Under one third of the men drafted actually were inducted into the army, “more than one-fifth (161,000 of 776,000) “failed to report” and about 300,000 “were exempted for physical or mental disability or because they convinced the inducting officer that they were the sole means of support for a widow, an orphan sibling, a motherless child, or an indigent parent.” [72]

There was also a provision in the Federal draft law that allowed well off men to purchase a substitute who they would pay other men to take their place. Some 26,000 men paid for this privilege, including future President Grover Cleveland. Another “50,000 Northerners escaped service by another provision in the Enrollment Act known as “commutation,” which allowed draftees to bay $300 as an exemption fee to escape the draft.” [73] Many people found the notion that the rich could buy their way out of war found the provision repulsive to the point that violence ensued in a number of large cities.

The Union draft law provoked great resentment, not because people were unwilling to serve, but from the way that it was administered, for it “brought the naked power of military government into play on the home front and went much against the national grain.” [74] Open clashes and violence erupted in several cities and President Lincoln was forced to use Union Soldiers, recently victorious at Gettysburg to end the rioting and violence taking place in New York where protestors involved in a three day riot, many of whom were Irish immigrants urged on by Democratic Tammany Hall politicians, “soon degenerated into violence for its own sake” [75] wrecking the draft office, seizing the Second Avenue armory, attacking police and soldiers on the streets. Soon “the mob had undisputed control of the city.” [76] These rioters also took out their anger on blacks, and during their rampage the rioters “had lynched black people and burned the Colored Orphan Asylum.” [77] The newly arrived veteran Union troops quickly and violently put down the insurrection and “poured volleys into the ranks of protestors with the same deadly effect they had produced against the rebels at Gettysburg two weeks earlier.” [78] Republican newspapers which supported abolition and emancipation were quick to point out the moral of the riots; “that black men who fought for the Union deserved more respect than white men who fought against it.” [79]

Notes

[1] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.19

[2] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lighteningp.141

[3] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.141

[4] McPherson, James M. Drawn With the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1996 pp.17-18

[5] Ibid. Weigley, American Strategy from Its Beginnings through the First World War in Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age p.419

[6] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.213

[7] Ibid Waugh The Class of 1846, p. 513

[8] Ibid Waugh The Class of 1846, pp. 512-513

[9] Ibid Waugh The Class of 1846, p. 513

[10] Ibid Waugh The Class of 1846, p. 513

[11] Ibid Waugh The Class of 1846, p. 513

[12] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.213

[13] Millet, Allan R. and Maslowski, Peter For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, revised and expanded edition The Free Press, New York 1994 p.175

[14] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.143

[15] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.143

[16] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.142

[17] Moe, Richard The Last Full Measure: The Life and Death of the 1st Minnesota Volunteers Minnesota Historical Society Press, St Paul MN 1993 p.13

[18] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.6

[19] Glatthaar, Joseph T. General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse The Free Press, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2008 p.15

[20] McCurry, Stephanie Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South Harvard University Press, Cambridge and London 2010 pp. 82-83

[21] Rhodes, Robert Hunt ed. All for the Union: The Civil War Diaries and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes, Vintage Civil War Library, Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 1985 p.4

[22] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.18

[23] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.24

[24] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.263

[25] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.15

[26] Ibid. Millet and Maslowski For the Common Defensep.165

[27] Sheehan-Dean, Aaron Confederate Enlistment in Civil War Virginia in Major Problems in the Civil War and Reconstruction, Third Edition edited by Michael Perman and Amy Murrell Taylor Wadsworth Cengage Learning Boston MA 2011 p.189

[28] Ibid. Glatthaar General Lee’s Army from Victory to Collapse p.26

[29] Ibid. Millet and Maslowski For the Common Defensep.165

[30] Sears, Stephen W. Controversies and Commanders Mariner Books, Houghton-Mifflin Company, Boston and New York 1999 p.201

[31] Ibid. Sears Controversies and Commanders p.201

[32] Swanberg, W.A. Sickles the Incredible copyright by the author 1958 and 1984 Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg PA 1991 p.117

[33] Keneally, Thomas American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles Anchor Books a Division of Random House 2003 p.222

[34] Ibid. Millet and Maslowski For the Common Defensep.165

[35] Ibid. Millet and Maslowski For the Common Defensep.165

[36] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.142

[37] Nichols, Edward J. Toward Gettysburg: A Biography of John Fulton Reynolds Pennsylvania State University Press, Philadelphia 1958. Reprinted by Old Soldier Books, Gaithersburg MD 1987 p.78

[38] Ibid. Weigley, American Strategy from Its Beginnings through the First World War in Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age p.419

[39] Ibid. Sears Controversies and Commanders p.202

[40] Ibid. Swanberg, Sickles the Incredible p.117

[41] Ibid. Millet and Maslowski For the Common Defensep.172

[42] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.328

[43] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.328

[44] Bruce, Susannah Ural The Harp and the Flag: Irish American Volunteers and the Union Army, 1861-1865 New York University Press, New York and London 2006 pp.54-55

[45] Ibid. Bruce The Harp and the Flag p55

[46] Gallagher, Gary W. The Union War Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London 2011

[47] Ibid. Robertson Soldiers Blue and Gray p.28

[48] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lighteningp.143

[49] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.328

[50] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.245

[51] Ibid. Nichols Toward Gettysburg p.79

[52] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.246

[53] Fuller, J.F.C. Decisive Battles of the U.S.A. 1776-1918 University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln 2007 copyright 1942 The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals p.182

[54] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.12

[55] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.37

[56] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.38

[57] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.143

[58] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.143

[59] Thomas, Emory The Confederate Nation 1861-1865 Harper Perennial, New York and London 1979 p.74

[60] Gallagher, Gary W. The Confederate War: How Popular Will, Nationalism and Military Strategy Could not Stave Off Defeat Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London 1999 p.34

[61] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.152

[62] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.152

[63] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p. 432

[64] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.154

[65] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.431

[66] Millet, Allan R. and Maslowski, Peter, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States The Free Press a Division of Macmillan Inc. New York, 1984 p.166

[67] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.433

[68] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.431

[69] Ibid. Thomas, The Confederate Nation p.261

[70] Ibid. Gallagher The Confederate War p.28

[71] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.600

[72] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.601

[73] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.460

[74] Ibid. Foote. The Civil War, A Narrative Volume Two p.635

[75] Ibid. Foote. The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.636

[76] Ibid. Foote. The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.637

[77] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.687

[78] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.610

[79] Ibid. McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.687