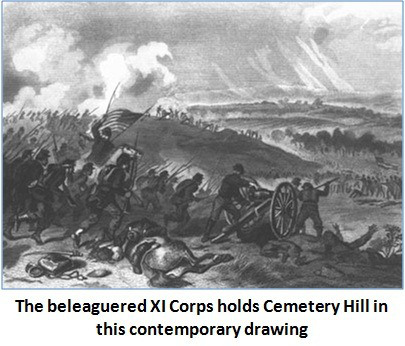

Major General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker

Friends: This is a major revision of the two part “Lee Moves North” that I put out Monday and Tuesday. I depart tomorrow with my students for our Gettysburg Staff Ride and in this revision I concentrate a lot more on the impact of “Fighting Joe” Hooker on the Army of the Potomac, the “General’s Revolts” that afflicted it and the events leading to Hookers relief during the Gettysburg campaign.

All are very important parts of the story, for despite his personal failings as a commander Hooker set his successors up for success and renewed the spirit of the army through some great reforms which impacted the personal welfare, health, moral and training of his soldiers. His organizational and administrative reforms, which created the Cavalry Corps, the Bureau of Military Information (Intelligence) and more effective medical, sanitary and logistical organizations, set him apart in ways that we often fail to appreciate.

I have taken the time to go into those topics because they have a major effect on the Union victory at Gettysburg. Hooker is a far more complex figure than we often give him credit for; he was a man of brilliance and bravery who had many major character flaws. Likewise I discuss other key figures, men also with feet of clay; J.E.B Stuart, Richard Ewell, Henry Halleck figuring prominently among them.

I think that putting them in this chapter makes the examination of Lee’s movement and the Federal pursuit more pertinent to us as leaders, because the things that Hooker does, for good and bad are issues that military, political and even business or non-profit leaders face. The additions of these parts of the story are important because they show the complexity of flawed people having to make major decisions, in crisis that impact the lives of all of us.

Movement to attain operational reach and maneuver are two critical factors in joint operations. In the time since the American Civil War the distances that forces move to engage the enemy, or maneuver to employ fires to destroy his forces have greatly increased. Movement may be part of an existing Campaign Plan or Contingency Plan developed at Phase 0; it also may be part of a crisis action plan developed in the midst of a campaign. Lee’s movement to get to Gettysburg serves as an example of the former, however, since his forces were already in contact with the Army of the Potomac along the Rappahannock and he was reacting to what he felt was a strategic situation that could not be changed but by going on the offensive that it has the feel of a Crisis Action Plan. Within either context other factors come into play: clarity of communications and orders, security, intelligence, logistics and even more importantly the connection between operational movement and maneuver; the Center of Gravity of the enemy, and national strategy. Since we have already discussed how Lee and the national command authority of the Confederacy got to this point we will discuss the how that decision played in the operational and tactical decisions of Lee and his commanders as the Army of Northern Virginia began the summer campaign and the corresponding actions of Joseph Hooker and the his superiors in Washington.

In the case of Hooker, far more than issues of strategy or operations were involved. Politics, personal rivalries and the personal insecurity of an Army commander played a big role in the drama that engulfed the Army of the Potomac as it pursued Lee’s Army. Additionally the ethics of the leaders involved, especially that of the generals of the Army of the Potomac during their “General’s Revolts” against McClellan, Burnside and Hooker had a major impact on the campaign. These factors all impacted Joe Hooker’s ability to command his army. They affected his relationships with his superiors and subordinates alike, and demonstrate how interconnected all of these elements are in the context of leading, campaigning and conducting the business of war.

“One of the fine arts of the military craft is disengaging one’s army from a guarding army without striking sparks and igniting battle.” [1] On June 3rd 1863 Robert E Lee began to move his units west, away from Fredericksburg to begin his campaign to take the war to the North. He began his exfiltration moving Second Corps under Richard Ewell and First Corps under James Longstreet west “up the south bank of the Rappahannock to Culpepper, near which Hood and Pickett had been halted on their return from Suffolk.” [2] Rodes’ division of Second Corps followed on June 4th with Anderson and Early on June 5th. Lee left the three divisions of A.P. Hill’s Third Corps at Fredericksburg to guard against any sudden advance by Hooker’s Army of the Potomac toward Richmond. Lee instructed Hill to “do everything possible “to deceive the enemy, and keep him in ignorance of any change in the disposition of the army.” [3]

The army was tremendously confident as it marched away from the war ravaged, dreary and desolate battlefields along the Rappahannock “A Captain in the 1st Virginia averred, “Never before has the army been in such a fine condition, so well disciplined and under such complete control.” [4] Porter Alexander wrote that he felt “pride and confidence…in my splendid battalion, as it filed out of the field into the road, with every chest & and ammunition wagon filled, & and every horse in fair order, & every detail fit for a campaign.” [5] Another officer wrote to his father, “I believe there is a general feeling of gratification in the army at the prospect of active operations.” [6]

Lee’s plan was to “shift two-thirds of his army to the northwest and past Hooker’s flank, while A.P. Hill’s Third Corps remained entrenched at Fredericksburg to observe Hooker and perhaps fix him in place long enough for the army to gain several marches on the Federals.” [7] In an organizational and operational sense that Lee’s army after as major of battle as Chancellorsville “was able to embark on such an ambitious flanking march to the west and north around the right of the army of the Potomac….” [8]

However, Lee’s movement did not go unnoticed; Hooker’s aerial observers in their hot air balloons “were up and apparently spotted the movement.” [9] But Hooker was unsure what it meant. He initially suspected that “Lee intended to turn the right flank of the Union army as he had done in the Second Bull Run Campaign, either by interposing his army between Washington and the Federals or by crossing the Potomac River.” [10] Lee halted at Culpepper from which he “could either march westward over the Blue Ridge or, if Hooker moved, recontract at the Rappahannock River.” [11]

“Fighting Joe” Hooker had been in command of the Army of the Potomac about five months, assuming command from Burnside, who Lincoln had relieved after that general had demanded the wholesale firing of ten generals from the army of the Potomac, including Hooker. Hooker was a graduate of West Point, class of 1837 and veteran of the Mexican War. However, he was not well regarded by many of his peers. “While on Garrison duty in California in the 1850s, he cultivated “bad habits and excesses”- too much liquor, and too many women. He left the army, failed at business, and amassed gambling debts and legal problems.” [12]

When war came Hooker managed to obtain an appointment as a Brigadier General of volunteers over the objections of General Winfield Scott from McClellan. He was a “capable commander and brave soldier” [13] but Hooker worked shamelessly against previous army commanders, including George McClellan, who he owed his appointment as a Brigadier General in the Regular Army. Hooker was “a strikingly handsome man” with “erect soldierly bearing…” but he was also “arrogant and stubborn, more than willing to work behind the scenes to advance himself, and reputed to have a headquarters that Charles Francis Adams Jr. described as “a combination barroom and brothel.” [14] The commander of XII Corps, Henry Slocum had “no faith whatever in Hooke’s ability as a military man, in his integrity or honor.” [15] However, George Meade was more circumspect, and wrote to his wife “He is a very good soldier, capital general for an army corps, but I am not prepared to say as to his abilities for carrying out a campaign and commanding a large army. I should fear his judgment and prudence…” [16]

Hooker genuinely believed in his abilities and much of the “criticism which he so freely bestowed on his superiors came simply because his professional competence was outraged by the blunders that he had to witness.” [17] But his enemies, “there would be a host of them- regarded him as “thoroughly unprincipled.” Hooker was driven by an “all consuming” ambition and undoubted self-confidence…. War intoxicated hi m and offered salvation for a troubled life. As a gambler he liked the odds.” [18]

During the war Hooker used the media to shamelessly promote his image and “deliberately played up to the press to swell his image as a stern, remorseless campaigner, and he reveled in the nickname the newspapers happily bestowed on him, “Fighting Joe.” [19] However, he would later express his “deep regret that it was ever applied to him. “People will think that I am a highwayman or bandit,” he said; when in fact he was one of the most kindly and tender-hearted of men.” [20]

But Hooker was not just disrespectful of his military superiors, but also of Abraham Lincoln who he told reporters after Fredericksburg “was an imbecile for keeping Burnside on but also in his own right, and that the administration itself “was all played out.” What the country needed was a dictator….” [21] Hooker was an intriguer for sure but unlike many generals who did so anonymously, he was open and public going before the “Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War investigating Fredericksburg” [22] where he not only provided damning testimony against Burnside, but against potential rivals.

When Lincoln appointed him, he gave Hooker a letter unique in American military history. In it Lincoln lectured Hooker as to his conduct while under the command of Burnside, “and just how much he disapproved of the unbounded ambition Hooker had displayed in Undercutting Burnside.” [23] In the letter and during his meeting with Hooker Lincoln laid out his expectations, as well as concerns that he had for him in his new command:

“you may have taken counsel of your ambition, and thwarted him as much as you could, in which you did a great wrong to the country.” Continuing: “I have heard, in such a way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I ask now is military success, and I will risk dictatorship.” [24] However, Lincoln pledged his support to Hooker saying “The government will support you to the utmost of its ability” but warned “I much fear the spirit which you have aided to infuse into the army, of criticizing their commander and withholding confidence in him, will now turn upon you. I shall assist you as far as I can to put it down. Neither you, nor Napoleon, if he were alive again, could get any good out of an army while such a spirit prevails in it.” [25]

Never before or since has an officer been given such responsibility by a President who recognized the man’s qualities, in this case a fighting spirit, as well as his personal vices, and shortcomings in character. Lincoln finished the latter with the admonition “And now, beware of rashness. Beware of rashness, but with energy and sleepless vigilance go forward and give us victories.” [26]

Hooker’s reaction to the letter was an interesting commentary to say the least. He recalled a few days later that, when he read it he “informed him personally of the great value I placed on the letter notwithstanding his erroneous views of myself, and that sometime I intended to have it framed and posted in some conspicuous place for the benefit of those who might come after men.” [27] Hooker was certainly sincere in this as he not only preserved it but ensured that it was published.

Despite the misgivings of the President and many of his peers, Hooker began a turnaround in the army that changed it for the better. At the beginning of his tenure he inspired confidence among his troops. He reorganized the Cavalry Corps and instituted reforms. Hooker discarded Burnside’s failed “Grand Division” organization and returned to the corps system. He was aided by experienced Corps commanders who had earned their promotions in combat and not due to political patronage, even the political animal Dan Sickles of III Corps had shown his abilities as a leader and commander, gone were the last remnants of McClellan’s regime.

Despite the many positives gained during the reorganization, Hooker made one significant mistake during the reorganization which hurt him at Chancellorsville, he decided to “strip General Hunt of command of the artillery and restrict him to purely administrative duties…he had restored Hunt to command the night of May 3 after the Confederates had driven him out of Chancellorsville,” ensuring that “The advantages traditionally possessed by the Union artillery in the quality of its material and cannon disappeared in this battle through Hooker’s inept handling of his forces.” [28]

Hooker was popular with the men as he conducted reforms which improved their lives. “He took immediate steps to cashier corrupt quartermasters, improve food, clean up the camps and hospitals, grant furloughs, and instill unit pride by creating insignia badges for each corps…Sickness declined, desertions dropped, and a grant of amnesty brought back many AWOLs back into the ranks.” [29] Additionally “paydays were reestablished and new clothing issued…. Boards of inspection searched out and dismissed incompetent officers.” [30]

But nothing impacted morale more that his order that “soft bread would henceforth be issued to the troops four times a week. Fresh potatoes and onions were to be issued twice a week, and desiccated vegetables once a week.” [31] The impact of the army commander actually caring for his troops was singularly important and far reaching. One officer wrote home “His ‘soft bead’ order reaches us in a tender spot….” [32] Regimental commanders were ordered to ensure that “regular company cooks went to work, and if there were no company cooks they were instructed to create some, so that the soldier could get some decent meals in place of the intestine-destroying stuff he cooked for himself.” [33] Hooker announced “My men shall eat before I am fed, and before my officers are fed” and he clearly meant it.” [34]

Additionally Hooker reformed training in the army. He knew that bored soldiers were their own worst enemy, and instituted a stringent training regimen that paid dividends on the battlefield. “From morning to night the drill fields rumbled with the tramp of many feet. Officers went to school evenings and the next day went out to maneuver companies, regiments, brigades, and divisions in the tactics just studied.” [35]

Hooker ridded himself of the last vestiges of McClellan’s reliance on the Pinkerton detective agency for his intelligence and created a “Bureau of Military Intelligence, led by Colonel George Sharpe” who “built a network of spies, who soon supplied Hooker with accurate information on Lee’s numerical strength and the unit composition of the Confederate army.” [36] He also reorganized and systematized the Medical department, and “placed it under the supervision of the competent medical director Dr. Jonathan Letterman.” [37]

It was a remarkable turnaround which even impressed his soldiers, his critics, and enemies and his enemies alike. Within weeks, “sick rolls had been reduced, and by April, scurvy had virtually disappeared. A veteran contended that Hooker “is a good man to feed an army for we have lived in the best since he took command that we ever did since we have been in the army.” [38] Darius Couch of Second Corps, who later resigned and became Hooker’s arch-enemy, wrote that Hooker had, “by adopting vigorous measures stopped the almost wholesale desertions, and infused new life and discipline into the army.” [39]

After the disaster at Chancellorsville Hooker was not the same. During that battle it was as if he was two persons. During the campaign Hooker had: “planned his campaign like a master and carried out the first half with great skill, and then when the pinch came he simply folded up. There had been no courage in him, no life, no spark; during most of the battle the army had to all intents and purposes had no commander at all.” [40] Hooker, a slave to his vanity had little capacity for reflection and blamed various corps commanders for the defeat, refusing to take any responsibility for it. Years later, Hooker when asked about the defeat, “knew a rare moment of humility and remarked, “Well, to tell the truth, I just lost confidence in Joe Hooker.” [41]

As such just as Lincoln had predicted there were many, both in the army and without who were clamoring for Hooker’s relief, especially after Hooker refused to take the blame for the defeat and instead blamed his subordinates. The blowback was fierce “the army high command took offense and closed ranks against the general commanding,” [42] and the “dissension between Hooker and his senior generals seethed for weeks.” [43]

Major General Henry Halleck

Halleck, who came to the army’s base at Falmouth to assess the army in wake of the defeat, “set the conspirators to work…called the corps commanders into counsel” and “learned of the great dissatisfaction among the higher officers….” [44] Hooker now found that the same knives which he had used on Burnside, “were now turned on him.” [45] Henry Slocum of XII Corps “went among his fellow corps commanders proposing a coup- a petition the president then and there to dismiss Hooker and put George Gordon Meade, commander of the Fifth Corps in his place” [46] but Meade balked at the idea. Lincoln had heard so much dissention that he wrote Hooker to warn him “that some of your Corps and Division Commanders are not giving you their entire confidence.” [47]

Such activities led to discussions at the White House to see if a new commander should lead the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln did interview John Reynolds of I Corps in early June to see if he wound take command, and Reynolds reportedly turned Lincoln down. Others were approached as well, and some officers even lobbied for the return of McClellan. Under this cloud Hooker went into the Gettysburg campaign.

Hooker telegraphed Lincoln and Halleck on June 5th and requested permission to advance cross the river and told Lincoln that “I am of opinion that it is my duty to pitch into his rear” [48] possibly to threaten Richmond. Lincoln ordered Hooker to put the matter to Halleck, with whom Hooker was on the worst possible terms. Hooker “pressed Halleck to allow him to cross the Rappahannock in force, overwhelming whatever rebel force had been left at Fredericksburg, and then lunging down the line of the Virginia Central toward an almost undefended Richmond.” [49] On the morning of June 6th 1863 Hooker ordered pontoon bridges thrown across the river and sent a division of Sedgwick’s VI Corps to conduct a reconnaissance in force against Hill.

Lincoln and Halleck immediately rejected Hooker’s request. Lincoln “saw the flaw in Hooker’s plan at once” [50] and replied in a very blunt manner: “In one word,” he wrote “I would not take any risk of being entangled upon the river, like an ox jumped half over a fence and liable to be torn by dogs front and rear, without a fair chance to gore one way or kick another.” [51] Halleck replied to Hooker shortly after Lincoln that it would “seem perilous to permit Lee’s main force to move upon the Potomac [River] while your army is attacking an intrenched position on the other side of the Rappahannock.” [52] Lincoln, demonstrating a keen regard for the actual center of gravity of the campaign, told Hooker plainly that “I think Lee’s army and not Richmond, is your objective point.” [53]

The fears of Lincoln and Halleck were well founded. In stopping at Culpepper Lee retained the option of continuing his march to the Shenandoah and the Potomac, or he could rapidly “recall his advanced columns, hammer at Hooker’s right flank, and very possibly administer another defeat even more demoralizing than the one he suffered at Chancellorsville.” [54] Hooker heeded the order and while Hooker maintained his bridgehead over the Rappahannock he made no further move against Hill’s well dug in divisions.

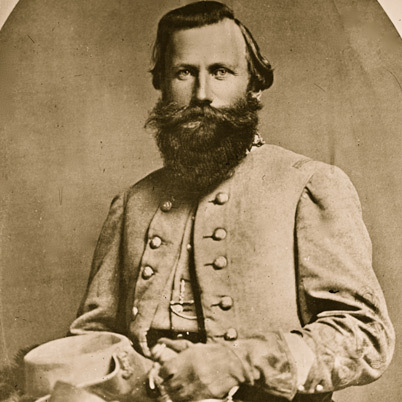

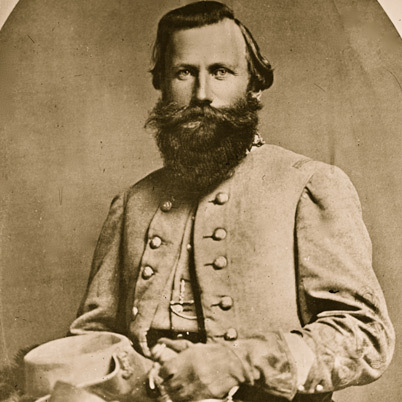

Major General J.E.B. Stuart

Meanwhile, J.E.B. Stuart and his Cavalry Corps had been at Brandy Station near Culpepper for two weeks. Culpepper in June was a paradise for the cavalry, and with nearly 10,000 troopers gathered Stuart ordered a celebration, many dignitaries were invited and on June 4th Stuart hosted a grand ball in the county courthouse. On the 5th Stuart staged a grand review of five of his brigades. Bands played as each regiment passed in review and one soldier wrote that it was “One grand magnificent pageant, inspiring enough to make even an old woman feel fightish.” [55] The review ended with a mock charge by the cavalry against the guns of the horse artillery which were firing blank rounds. According to witnesses it was a spectacular event, so realistic and grand that during the final charge that “several ladies fainted, or pretended to faint, in the grandstand which Jeb Stuart had had set up for them along one side of the field.” [56] That was followed by an outdoor ball “lit by soft moonlight and bright bonfires.” [57] Stuart gave an encore performance when Lee arrived on June 8th, minus the grand finale and afterward Lee wrote to his wife that “Stuart was in all his glory.” [58]

Hooker received word from the always vigilant John Buford, of the First Cavalry Division on the night of June 6th that “Lee’s “movable column” was located near Culpepper Court House and that it consisted of Stuart’s three brigades heavily reinforced by Robertson’s, “Grumble” Jones’s, and Jenkins’ brigades.” [59] Hooker digested the information and believed that Stuart’s intent was to raid his own rear areas to disrupt the Army of the Potomac’s logistics and communications. The next day Hooker ordered his newly appointed Cavalry Corps Commander, Major General Alfred Pleasanton to attack Stuart.

After Chancellorsville, Hooker had reorganized the Union cavalry under Pleasanton into three divisions and under three aggressive division commanders, all West Pointers, Brigadier General John Buford, Brigadier General David Gregg and Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick. While Stuart conducted his second grand review for Lee Pleasanton quietly massed his cavalry “opposite Beverly Ford and Kelly’s Ford so as to cross the river in the early morning hours of June 9th and carry out Hooker’s crisp orders “to disperse and destroy” the rebel cavalry reported to be “assembled in the vicinity of Culpepper….” [60] Pleasanton’s cavalry was joined by two mixed brigades of infantry “who had the reputation of being among the best marchers and fighters in the army.” [61] One brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Adelbert Ames consisted of five regiments drawn from XI Corps, XII Corps, and III Corps was attached to Buford’s division. The other brigade, under the command of Brigadier General David Russell was composed of seven regiments drawn from I Corps, II Corps and VI Corps. [62]

Stuart’s orders for June 9th were to “lead his cavalry division across the Rappahannock to screen the northward march of the infantry.” [63] The last thing that Stuart expected was to be surprised by the Federal cavalry which he had grown to treat with distain. Stuart who was at his headquarters “woke to the sound of fighting” [64] as Pleasanton’s divisions crossed the river and moved against the unsuspecting Confederate cavalry brigades.

The resultant action was the largest cavalry engagement of the war. Over 20,000 troopers engaged in an inconclusive see-saw battle that lasted most of the day. Though a draw “the rebels might have been swept from the field had Colonel Alfred N. Duffie, at the head of the Second Division acted aggressively and moved to the sounds of battle.” [65] The “Yankees came with a newfound grit and gave as good as they took.” [66] Porter Alexander wrote that Pleasanton’s troopers “but for bad luck in the killing of Col. Davis, leading the advance, would have probably surprised and captured most of Stuart’s artillery.” [67] Stuart had lost “over 500 men, including two colonels dead,” [68] and a brigade commander, Fitzhugh “Rooney” Lee, General Lee’s son, badly wounded. While recuperating at his wife’s home a few weeks later Lee “was captured by the enemy.” [69] Stuart claimed victory as he lost fewer troops and had taken close to 500 prisoners and maintained control of the battlefield.

But even Confederate officers were critical. Lafayette McLaws of First Corps wrote “our cavalry were surprised yesterday by the enemy and had to do some desperate fighting to retrieve the day… As you will perceive from General Lee’s dispatch that the enemy were driven across the river again. All this is not true because the enemy retired at their leisure, having accomplished what I suppose what they intended.” [70] Captain Charles Blackford of Longtreet’s staff wrote: “The fight at Brandy Station can hardly be called a victory. Stuart was certainly surprised, but for the supreme gallantry of his subordinate officers and men… it would have been a day of disaster and disgrace….” The Chief of the Bureau of War in Richmond, Robert H.G. Kean wrote “Stuart is so conceited that he got careless- his officers were having a frolic…” [71] Brigadier General Wade Hampton had the never to criticize his chief in his after action report and after the war recalled “Stuart managed badly that day, but I would not say so publicly.” [72]

The Confederate press was even more damning in its criticism of Stuart papers called it “a disastrous fight,” a “needless slaughter,” [73]and the Richmond Examiner scolded Stuart in words that cut deeply into Stuart’s pride and vanity:

“The more the circumstances of the late affair at Brandy Station are considered, the less pleasant do they appear. If this was an isolated case, it might be excused under the convenient head of accident or chance. But the puffed up cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia has twice, if not three times, surprised since the battles of December, and such repeated accidents can be regarded as nothing but the necessary consequences of negligence and bad management. If the war was a tournament, invented and supported for the pleasure of a few vain and weak-headed officers, these disasters might be dismissed with compassion, But the country pays dearly for the blunders which encourage the enemy to overrun and devastate the land, with a cavalry which is daily learning to despise the mounted troops of the Confederacy…” [74]

Major General Dorsey Pender waxed philosophically about the criticism of Stuart in a letter to his wife saying “I suppose it is all right that Stuart should get all the blame, for when anything handsome is done he gets all the credit.” [75] Stuart reacted angrily to the criticism; his vanity was such that it was impossible. Stuart denied being surprised and his Chief of Staff; Major Henry McClellan wrote “He could never see or acknowledge …that he was worsted in an engagement.” [76]

But the battle was more significant than the number of casualties inflicted or who controlled the battlefield at the end of the day. Stuart had been surprised by an aggressively led Union Cavalry force. The Union troopers fought a stubborn and fierce battle and retired in good order. Stuart did not appreciate it but the battle was a watershed, it signaled the beginning of the end of the previous dominance of the Confederate Cavalry arm over their Union opponents.

Henry McClellan wrote that Brandy Station “made the Federal cavalry. Up to that time confessedly inferior to the Southern horsemen, they gained on this day that confidence in themselves and in their commanders which enabled them to contest so fiercely the subsequent battle-fields….” [77] The Richmond Examiner noted “The enemy is evidently determined to employ his cavalry extensively, and has spared no pains to perfect that arm.” [78] That determination to perfect the Union cavalry was something that in less than a years’ time would cost Stuart his life when his outnumbered and ill troopers met Phil Sheridan’s well led, trained and equipped troops at Yellow Tavern outside of Richmond on May 11th 1864.

The action at Brandy Station delayed Lee’s movement by a day. However, Stuart’s repulse of Pleasanton’s force did enable Lee’s Army to make its northward movement undetected by Hooker who was still trying to divine what Lee was up to and was “slow, even reluctant, to react to Lee’s advance.” [79] Lee’s initial move to break contact with the Federal Army and keep his movements and intentions secret was an excellent example of deception.

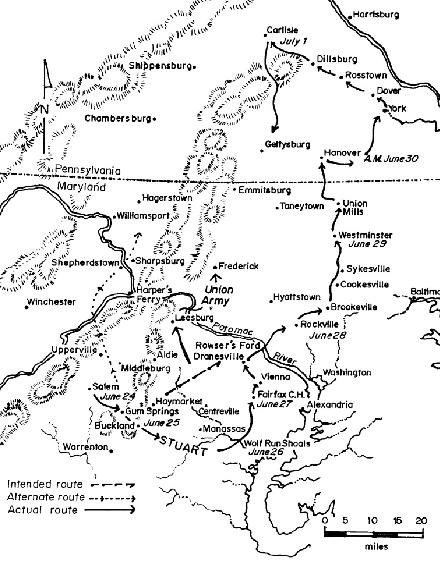

Major General Richard Ewell

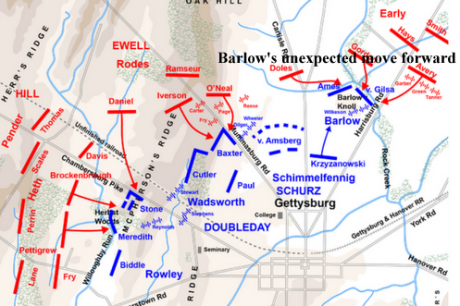

Ewell’s Corps led the march of the army north on the morning of June 10th and joined by Jenkins’ cavalry brigade entered the Shenandoah Valley by way of the Chester Gap on June 12th. In two days of marching his “columns covered over forty-five miles.” [80] On the 13th Ewell was near Winchester where 6,000 soldiers under the command of Major General Robert Milroy were garrisoned. Ewell’s advanced troops skirmished with them on June 13th, and on the 14th Ewell concentrated his corps to attack Milroy’s badly exposed division. As he did so Lincoln and Halleck attempted to get Milroy to withdraw to Harper’s Ferry and for Hooker to do something to attempt to relieve Milroy.

But Hooker was “troubled by indecision” [81] and did nothing. Ewell commenced his attack at about 5:00 PM, and deployed Johnson’s division in an ambush position north of the city to catch Milroy if he attempted to withdraw. The battle, now known as the Second Battle of Winchester the battle was a complete rout. Hit by Ewell’s forces “which swiftly and effectively broke through his outer lines,” [82] Milroy attempted to retreat “northwestward in the darkness, only to be intercepted at dawn by Johnson.” [83] The Second Corps captured “captured 23 cannon, 300 wagons loaded with supplies and ammunition, and nearly 4,000 prisoners.” [84] Milroy and his survivors retreated to Harper’s Ferry where he was “presently removed from command by Lincoln, but that was a superfluous gesture, since practically all of his command had been removed from him by Ewell.” [85] Ewell’s forces lost just 50 killed and 236 wounded.

Ewell’s decisive victory at Winchester “was one of the most swift, total, and bloodless Confederate victories of the war.” [86] The victory “cleared the lower Shenandoah Valley of most Federal forces and paved the way for Lee’s army to march north into Maryland and then into Pennsylvania.” [87] Ewell had been brilliant to this point, the victory at Second Winchester and the skill with which he had conducted his operations had “removed lingering doubts about his ability to carry on the tradition of “Stonewall” Jackson, as well as about his physical capacity, after the loss of a leg, to endure the rigors of campaigning.” [88] The Richmond Daily Dispatch that Ewell “has indeed caught the mantle of the ascended Jackson. Brilliantly has he re-enacted the scenes of the spring of ’62, on the same theatre.” [89]

Ewell did not waste time lingering at Winchester. The next day he sent Jenkins with his brigade across the Potomac to Chambersburg Pennsylvania. Rodes division crossed the Potomac on the 16th “for a crossing at Williamsport where a halt was called to allow the other two divisions to catch up for a combined advance into Pennsylvania.” [90]

Longstreet’s First Corps moved next and advanced east of the Blue Ridge in conjunction with Stuart’s cavalry division screening the rest of the army from Hooker. Longstreet “set out for Ashby’s and Snicker’s Gaps with the bulk of Stuart’s cavalry covering his right flank.” [91] By the 17th of June Longstreet’s and Stuart’s troops had cleared the Blue Ridge, securing the vital gaps; however, Longstreet’s advance “was considerably slowed down by lack of supplies” [92] an issue that began to cause Lee, advancing behind Ewell, considerable concern. The once bountiful Shenandoah Valley had been devastated by two years of war. Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle, a British observed wrote “All fences have been destroyed, and numberless farms burned, their chimneys alone left standing….No animals are grazing and it is almost uncultivated.” [93]

But “Lee’s army was now stretched out from Hagerstown to Culpepper, a distance of seventy-five miles; yet Hooker did nothing.” [94] Lincoln realized that the dispersed Confederate army was vulnerable and telegraphed Hooker “if the head of Lee’s army is at Martinsburg and the tail of it on the Plank road between Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, the animal must be very slim somewhere. Could you not break him?” [95]

Hooker was slow to appreciate what Lee was doing and the “concealing topography of the region greatly favored Lee’s offensive operations…and Lee was planning on using both the Shenandoah and Loudoun valleys to conceal his forces and confuse his enemies.”[96] In this Lee had succeeded admirably. Finally on June 13th Hooker prodded by Lincoln and Halleck finally moved the Army of the Potomac to a position “near the Orange and Alexandria Railroad near Washington” [97] where it could defend Washington in case Lee was to make a thrust at the Federal capitol. The march from Fredericksburg was ordeal for his soldiers. “It had not rained for more than a month, thick clouds of dust enveloped the columns as the sun burned the air. Men drained their canteens, and water was scarce. Hundreds collapsed from sunstroke.” [98]

Hooker now informed Lincoln and Halleck that from now on his operations “would be governed by the movements of the enemy.” In doing so he “admitted his loss of initiative to Lee and his reluctance or inability to suggest any effective countermoves to the enemy’s plan.” [99]

As the army gathered near Dumfries on June 17th, Hooker who was completely lost as to Lee’s intentions and clearly out of his league was also chose to renew his personal battle with Halleck and Lincoln. Hooker’s Chief of Staff General Dan Butterfield, and a staunch Hooker partisan remarked “We cannot go boggling around until we know what we are going after.” [100] The Provost Marshall of the Army of the Potomac Brigadier General Marsena Patrick was not so generous and critically noted that “Hancock is running the Marching and Hooker has the role of a subordinate- He acts like a man without a plan and is entirely at loss at what to do, or how to match the enemy, or counteract his movements.” [101]

During the march Hooker continued his feud with Halleck and Lincoln, oblivious to the fact that “his contretemps with Washington was costing him respect and credibility.” [102] Navy Secretary Gideon Welles after talking with Lincoln wrote in his diary, “I came away from the War Department painfully impressed. After recent events, Hooker cannot have the confidence which is essential to success, and which is all-important to the commander in the field.” [103]

Hooker however, continued to make matters worse for himself and wrote Lincoln on June 16th, a thinly veiled attempt to have Halleck relieved:

“You have been aware, Mr. President” he telegraphed, “that I have not enjoyed the confidence of the major-general commanding the army, and I can assure you so long as this continues we may look in vain for success, especially as future operations will require our relations to be more dependent on each other than heretofore.” [104]

Lincoln was not to be trifled with by his demanding yet befuddled subordinate. He sent a telegraph to Hooker at 10:00 PM on the 16th which rankled Hooker even the more:

“To remove all misunderstanding I now place you in the strict military relation to General Halleck of a commander of one of the armies to the general-in-chief of all of the armies. I have not intended differently, but as it seems to be differently understood I shall direct him to give you orders and for you to obey him.” [105]

While the drama between Hooker, Halleck and Lincoln played on there were a series of fierce cavalry clashes west of Washington between June 17th and June 21st as Pleasanton’s troops kept assailing the Confederate flank in order to ascertain what Lee’s army was doing. As the Federal cavalry probed the gaps in the Blue Ridge they were confronted by Stuart’s cavalry. At Aldie on June 17th, Middleburg on June 19th and at Upperville on June 21st Stuart’s and Pleasanton’s troopers engaged “in a series of mounted charges and dismounted fighting. The Yankees showed the same grit and valor as they had at Brandy Station, pressing their attacks against the Rebels.” [106]

At Upperville Pleasanton’s troopers “pressed Stuart’s cavalry so hard that Lee ordered McLaws’ division of Longstreet’s Corps to hold Ashby’s Gap, and he momentarily halted Major General Richard Anderson’s division of Hill’s corps on its way to Shepherdstown.” [107] Stuart’s men were successful in protecting the gaps and ensuring that the Federal troopers did not penetrate them, but “Pleasanton learned, however, from prisoners and local citizens, “The main body of the rebel infantry is in the Shenandoah Valley.” [108]

Pleasanton for some unexplained reason thought that this meant that the Confederates were heading toward Pittsburgh. Hooker “viewed it as a raid” and again proposed an overland advance against Richmond, which was again rejected by Lincoln. The President ordered Hooker: “If he comes toward the Upper Potomac, follow on his flank and on his inside track, shortening your line whilst he lengthens his. Fight him too when the opportunity offers. If he stays where he is, fret him, fret him and fret him.” [109]

As the series of clashes occurred on the Confederate flank Ewell’s Second Corps, followed by Hill’s Third Corps advanced into Pennsylvania. A general panic ensued in many places with cries going out for Lincoln to call up militia to defend the state. The panic had begun when Ewell crushed Milroy’s garrison and crossed the Potomac, and was fueled by the actions of Jenkins’ troops, in occupied Chambersburg, who rounded up any blacks that remained in the city. Most blacks, even freedmen fled before the advancing Confederates, and with good reason. “Some fifty blacks were formed into a coffle and marched south to be sold into bondage.” [110] Gideon Welles wrote in Washington D.C.: “Something of a panic pervades the city this evening. Singular rumors of Rebel advances into Maryland. It is said that they have reached Hagerstown, and some of them have penetrated as far as Chambersburg.” [111] Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtain, a former Whig now a Republican aligned with Lincoln’s policies “was in political trouble now,” [112] was pressing the Federal government for help and “Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 100,000 militia volunteers form Pennsylvania, Maryland, Ohio and West Virginia, to serve for six months or until the emergency had passed.” [113]

By June 23rd the head of the Bureau of Military Information, Colonel George Sharpe had deduced that all of Ewell’s corps was in Pennsylvania marching north and that Hill’s corps was across the Potomac., and “in one of those sudden moments of brutal clarity, George Sharpe realized that everything pointed to the conclusion that Lee’s entire army, or most of it, was north of the Potomac.” [114] While Sharpe did not realize that he was incorrect in the location of Longstreet’s corps, which was still helping to hold and screen the gaps on the Blue Ridge, he had correctly deduced Lee’s intentions.

It took time but Hooker belatedly on June 24th began to move his army to Frederick. As the Army of the Potomac crossed its namesake river between June 25th and 27th over a vast pontoon bridge, Hooker made one last attempt to salvage his reputation, and did not believe that Lincoln was actually trying to help mediate his dispute with Halleck. Hooker made a quick trip into Washington on the 23rd of June. He met with Lincoln and was successful in getting Halleck to give him nearly 15,000 reinforcements drawn from the District of Washington, drawing the ire of its commander Major General Samuel Heintzelman, another of his political enemies. But the visit did not help his situation, and “word began to spread that Hooker was drinking a great deal.” [115]

But Hooker opened the door to more trouble by demanding that he be given command and control over the garrison at Harpers Ferry, allegedly to use in an operation to cut off Lee’s line of supply and communication in Western Maryland. Hooker attempted to bypass Halleck yet again and sent orders to affect his course of action to Slocum of XII Corps and William French at Harper’s Ferry, “yet Hooker told Washington nothing of his plan” and then asked Halleck why Harper’s Ferry could not be abandoned, and requested its troops without telling him how he would use the garrison. Hooker then informed Halleck that he “would go to Harper’s Ferry the next day and inspect the place.” [116] Hooker evidently believed that he could still force his will on Halleck with a coupe d ’main.

Halleck refused Hooker and shrewdly had seen the request coming. Halleck told Hooker “that the fortified heights at Harpers Ferry…”have always been regarded as an important point by to be held by us…I cannot approve their abandonment, except in the case of absolute necessity” [117] and directed the Major General William H. French, the commanding officer of the Harper’s Ferry garrison “Pay no attention to Hooker’s orders.” [118] When Hooker went to see French in Harper’s Ferry and saw the dispatch he was furious. In his anger Hooker “told Herman Haupt during the railroad coordinator’s visit that he would do nothing to oppose Lee’s invasion without specific orders. He also continued to tell Halleck, Stanton, and Lincoln that he wanted Lee to go north so he could go after Richmond.” [119]

The order to French was Halleck’s way of baiting Hooker to react badly. Halleck figured that Hooker would consider it the last straw, which was exactly what the impulsive Hooker did. Hooker then played his last card and wired Halleck an ultimatum, which in a sense he was using as a “club to bully Halleck into giving him a free hand in questions of strategy” and it is “questionable whether he expected Lincoln to accept his resignation.” [120]

“My original instructions require me to cover Harper’s Ferry and Washington. I have now imposed on me, in addition to an enemy in my front more than my number. I beg to be understood, respectfully, but firmly that I am unable to comply with this condition with the means at my disposal, and earnestly request that I be relieved from the position I occupy.” [121]

Halleck sent Hooker a brief message; simply stating “Your dispatch has been duly referred to the executive for action.” [122] He then took the letter to Stanton and Lincoln and Lincoln wasted little time in relieving Hooker, though he was not happy about having to do so in the middle of a campaign. Lincoln had two choices, “he could send him into battle with his self-doubts and suspicions intact, or he could accept it and risk the political and military consequences that would accompany an abrupt change in leadership.” [123] In less than half an hour Lincoln told Halleck and Stanton to “Accept his resignation. Before midnight, War Secretary Edwin Stanton’s own chief of staff, James Hardie, was on his way by train from Washington with Lincoln’s order removing Hooker from command.” [124]

In the end, late in the night of June 27th Lincoln chose the latter, relieved Hooker, and appointed Major General George Gordon Meade, commanding officer of V Corps as the new commander of the Army of the Potomac. He explained the decision to the cabinet the next morning; Gideon Welles wrote that Lincoln said “he had, for several days as the conflict became imminent, observed in Hooker the same failings that were witnessed in McClellan after the Battle of Antietam. – A want of alacrity to obey, and a greedy call for more troops which could not, and ought not be taken from other points….:” [125]

Hooker’s relief was a direct result of his “contretemps with General-in Chief Halleck, but it was the general’s revolt that set the stage for it. With virtually no support from his chief lieutenants…Hooker was pushed into a precarious position.” [126]

Despite Hooker’s lackluster performance during the campaign, his failings as a field commander, and his poor relationships with Lincoln, Halleck and many of his corps commanders, Hooker had made significant contributions to the Army of the Potomac and the nation:

“Whatever his mistakes, Hooker’s record as a military administrator ranks him near the top, for he refashioned the army into an effective fighting machine. He saved it from disintegration, gradually filled its ranks to peak strength, inflated its morale, and put it in a superb condition for the start of the spring campaign.” [127]

During his tenure of command, “the army had come of age. It was a professional army now in all but name.” [128] He had assumed command when the army was at its lowest fortune after Fredericksburg, “he instituted reform and restored their fighting spirit.” [129] His reorganization of the Cavalry Corps under solid officers was critical in the campaign and paid dividends for the rest of the war. His creation of the Bureau of Military Information was instrumental in providing George Meade at Gettysburg with accurate information about Lee’s army that he used to his advantage in conducting the battle. In spite of his flaws, Hooker had, even after the defeat at Chancellorsville kept the army together and in good fighting trim, even if his soldiers no longer believed in him, they believed in themselves.

During the opening weeks of the Gettysburg campaign, albeit through the prodding of Lincoln he had kept his army between Lee and Washington. But throughout the campaign Hooker seemed “plagued with uncertainty as to what he should do and what were his true military objectives. The tone of his correspondence with Washington authorities was continually querulous and angry.” [130] Hooker’s justified paranoia of Halleck and his and personal insecurity ensured that he made decisions that caused Lincoln to have even more reservations about his ability to command the army, and confront Robert E. Lee. Some have speculated that his recalcitrance in following Lincoln’s orders to confront Lee during the march was because he did not want to face Lee in battle once again. None of those factors can be ignored when assessing Hooker’s performance during his tenure of command of the Army of the Potomac. It was probably fortunate for the Union that Hooker asked to be relieved. His lack of confidence to face Lee in battle would have probably ensured defeat, but his reforms had set the army and its new commander up for success.

While the high drama in Washington and Pennsylvania unfolded Robert E. Lee, after an excellent beginning to his campaign was beginning to experience a drama of his own which would decisively impact his invasion of Pennsylvania.

Notes

[1] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg, Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 2003 p.59

[2] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.436

[3] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.25

[4] Wert, Jeffry D. A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph 1862-1863 Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2011 p.218

[5] Alexander, Edward Porter. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander edited by Gary Gallagher University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1989 p.221

[6] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.219

[7] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.60

[8] Korda, Michael. Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2014 p.530

[9] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.436

[10] Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2005 p.260

[11] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.37

[12] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.74

[13] Jordan, David M. Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier’s Life Indian University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1988 p.67

[14] Marszalek, John F. Commander of All of Lincoln’s Armies: A Life of General Henry W. Halleck The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London 2004 p.165

[15] Guelzo Allen C. Fateful Lightening: A New History of the Civil War Era and Reconstruction Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2012 p.331

[16] Huntington, Tom Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg PA 2013 p.127

[17] Catton, Bruce The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p.7

[18] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln pp.74-75

[19] Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.331

[20] Bates, Samuel P. Hooker’s Comments on Chancellorsville in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume III, The Tide Shifts. Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel Castle, Secaucus NJ p.217

[21] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.136

[22] Sears, Stephen W. Controversies and Commanders Mariner Books, Houghton-Mifflin Company, Boston and New York 1999 p.150

[23] Ibid. Sears Controversies and Commanders p.157

[24] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.219

[25] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two pp.132-133

[26] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.133

[27] Sears, Stephen W. Chancellorsville Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 1996 p.62

[28] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.31

[29] McPherson, James. The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1988 p.133

[30] Ibid. Sears. Chancellorsville p.73

[31] Ibid. Sears Chancellorsville p.73

[32] Ibid. Sears Chancellorsville p.73

[33] Ibid. Catton Glory Road p.143

[34] Ibid. Sears Chancellorsville p.73

[35] Ibid. Catton Glory Road p.145

[36] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.229

[37] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.225

[38] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln pp.225-226

[39] Ibid. Sears Controversies and Commanders p.157

[40] Ibid. Catton Glory Road p.210

[41] Ibid. Catton Glory Road p.211

[42] Ibid. Sears Controversies and Commanders p.158

[43] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.256

[44] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.19

[45] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.28

[46] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.19

[47] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.28

[48] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.61

[49] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.50

[50] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.260

[51] Fuller, J.F.C. Decisive Battles of the U.S.A. 1776-1918 University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln 2007 copyright 1942 The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals p.223

[52] Ibid Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.26

[53] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.50

[54] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.53

[55] Davis, Burke J.E.B. Stuart: The Last Cavalier Random House, New York 1957 p.304

[56] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.437

[57] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.63

[58] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.221

[59] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.54

[60] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.64

[61] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.54

[62] Petruzzi, J. David and Stanley, Steven The Gettysburg Campaign in Numbers and Losses: Synopses, Orders of Battle, Strengths, Casualties and Maps, June 9 – July 1, 1863 Savas Beatie LLC, El Dorado Hills CA 2012 p.7

[63] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.64

[64] Ibid. Davis JEB Stuart p.306

[65] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.261

[66] Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 1993 p. 251

[67] Ibid. Alexander Fighting for the Confederacy p.223

[68] Ibid. Davis JEB Stuart p.310

[69] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.221

[70] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.59

[71] Ibid. Davis JEB Stuart p.310

[72] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.60

[73] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.57

[74] Ibid. Davis JEB Stuart pp.311-312

[75] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.73

[76] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.221

[77] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.74

[78] Ibid. Davis JEB Stuart p.312

[79] Ibid. Wert General James Longstreet p.251

[80] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.73

[81] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.81

[82] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.88

[83] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.440

[84] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.222

[85] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.440

[86] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.62

[87] Ibid. Petruzzi and Stanley The Gettysburg Campaign in Numbers and Losses p.20

[88] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.89

[89] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.62

[90] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.440

[91] Ibid. Fuller Decisive Battles of the U.S.A. 1776-1918 p.224

[92] Ibid. Fuller Decisive Battles of the U.S.A. 1776-1918 p.225

[93] Ibid. Korda Clouds of Glory p.537

[94] Ibid. Fuller Decisive Battles of the U.S.A. 1776-1918 p.224

[95] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion pp.64-65

[96] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.85

[97] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.71

[98] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.263

[99] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.71

[100] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.264

[101] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage pp. 53-54

[102] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.53

[103] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.88

[104] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.88

[105] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.54

[106] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.264

[107] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.79

[108] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.224

[109] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.224

[110] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.82

[111] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.82

[112] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.101

[113] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln pp.264-265

[114] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.66

[115] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.63

[116] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.120

[117] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.93

[118] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.84

[119] Ibid. Marszalek, Commander of All of Lincoln’s Armies p.175

[120] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.131

[121] Ibid. Marsalek Commander of All of Lincoln’s Armies p.175

[122] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.123

[123] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.98

[124] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.84

[125] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.266

[126] Ibid. Sears Controversies and Commanders p.162

[127] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.31

[128] Ibid. Catton Glory Road p.217

[129] Ibid. Wert The Sword of Lincoln p.266

[130] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.133