Note: One of the most important things to understand about the Battle of Gettysburg or for that matter any battle or campaign is leadership as well as organizational structure and climate of command. The study of A.P. Hill’s Third Corps is important to understanding how the battle unfolds and what happens at Gettysburg particularly on July 1st. In our understanding “Successful mission command demands that subordinate leaders at all echelons exercise disciplined initiative, acting aggressively and independently to accomplish the mission. Essential to mission command is the thorough knowledge and understanding of the commander’s intent at every level of command.”

While the leaders at Gettysburg on both sides would be unaware of our present definition they certainly would have been acquainted with the maxims of Napoleon, who many studied under Dennis Hart Mahan at the West Point. Napoleon noted: “What are the conditions that make for the superiority of an army? Its internal organization, military habits in officers and men, the confidence of each in themselves; that is to say, bravery, patience, and all that is contained in the idea of moral means.”

Likewise in a maxim that has direct application to the Confederate campaign in Pennsylvania Napoleon noted “To operate upon lines remote from each other and without communications between them, is a fault which ordinarily occasions a second. The detached column has orders only for the first day. Its operations for the second day depend on what has happened to the main body. Thus according to circumstances, the column wastes its time in waiting for orders or it acts at random….” [1]

I have spent more time in this chapter developing the issues of organization, leadership, climate of command and relationships between leaders because of their importance to the campaign. From these students should be able to draw lessons that would be applicable to leadership, organization and campaigning at the operational level of war.

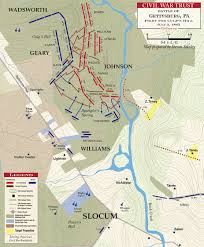

As the Army of Northern Virginia began to concentrate near Cashtown after the reports that the Army of the Potomac was in Maryland it was Lieutenant General A.P. Hill’s Third Corps that was nearest to Gettysburg. Major General Harry Heth’s division led the corps and arrived on June 29th followed by Major General Dorsey Pender’s division on the 30th. Hill ordered his last division under the command of Major General Richard Anderson to remain behind and join the corps on July 1st. [2]

On the 30th Harry Heth sent Johnston Pettigrew’s Brigade to Gettysburg to “search the town for army supplies (shoes especially), and to return the same day.” [3] It was the first in a series of miscalculations that brought Lee’s army into a general engagement that he wished to avoid.

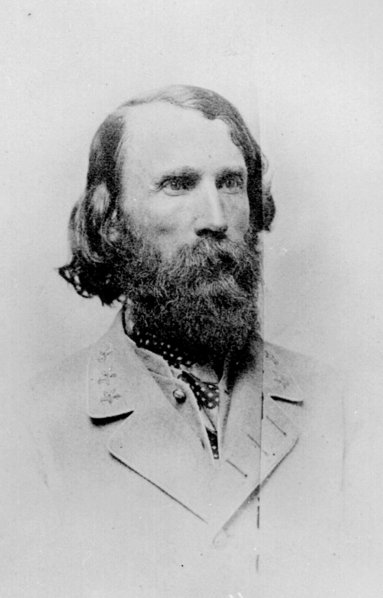

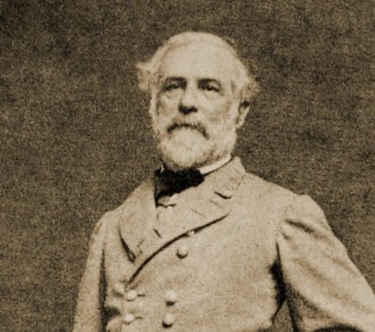

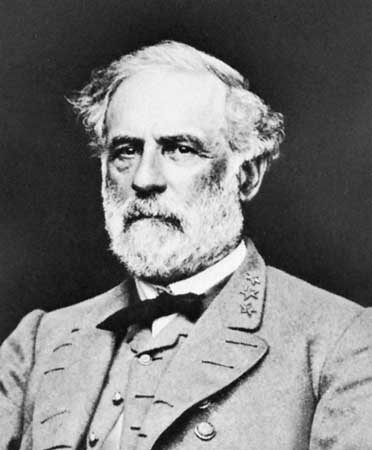

The Confederate Third Corps commanded by Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell (A.P.) Hill had been formed as part of the reorganization of the army following Stonewall Jackson’s death after the Battle of Chancellorsville. Hill had a stellar reputation as a division commander; his “Light Division” had distinguished itself on numerous occasions, especially at Antietam where its timely arrival after a hard forced march from Harper’s Ferry helped save Lee’s army late in the battle. At Chancellorsville Hill briefly succeeded Jackson until he too was wounded.

But that being said Hill was no stranger to controversy, beginning with a clash with James Longstreet during the Seven Days battles in which time Longstreet placed Hill under arrest and Hill challenged Longstreet to a duel. Lee quickly reassigned Hill to Jackson’s command as Jackson was operating in a semi-independent assignment. [4] Hill was in an intractable controversy with Stonewall Jackson for nearly a year until Jackson succumbed to his wounds. Jackson at one point during the invasion of Maryland prior to Antietam had Hill placed under arrest for the number of stragglers that he observed in Hill’s hard marching division as well as other errors that Jackson believed Hill had made. The dispute continued and the animosity deepened between the two men and in January 1863 Hill asked Lee for a trial by courts-martial on charges preferred against him by Jackson. Lee refused this and wrote to Hill: “Upon examining the charges in question, I am of the opinion that the interests of the service do not require that they be tried, and therefore, returned them to General Jackson with an indorsement to that effect….” [5] Just before Chancellorsville Jackson wrote to Lee “I respectfully request that Genl. Hill be relieved of duty in my Corps.” This time Lee simply ignored the request and though the two generals remained at loggerheads they also remained at their commands at Chancellorsville. [6]

Hill was recommended for promotion to Lieutenant General and command of the new Third Corps by Lee on May 24th and was promoted over the heads of Harvey Hill and Lafayette McLaws. The move displeased Longstreet who considered McLaws “better qualified for the job” and but who felt that the command should have gone to Harvey Hill whose “record was as good as that of Stonewall Jackson…but, not being a Virginian, he was not so well advertised.” [7]

Hill was slightly built and high strung. “Intense about everything” Hill was “one of the army’s intense disbelievers in slavery.” [8] Hill was an 1847 graduate of West Point and briefly served in Mexico but saw no combat. He spent some time in the Seminole wars and in garrison duty along the East Coast, spending 1855-1860 in the Coastal Survey and resigned his commission before Virginia’s secession. At the outbreak of the war he “received his commission as colonel, and soon trained one of Johnston’s best regiments in the Valley.” [9] He commanded a brigade under Longstreet on the Peninsula and was promoted to Major General and command of a division in May 1862. He was plagued by health problems which had even delayed his graduation from West Point, health issues that would arise on the first day at Gettysburg.

Hill’s Third Corps was emblematic of the “makeshift nature of the reorganization of the whole army.” [10] It was composed of three divisions; the most experienced being that of the recently promoted and hard fighting Major General Dorsey Pender. Pender’s division, was built around four excellent brigades from Hill’s old “Light Division” one of which Pender had commanded before his promotion. Hill strongly recommended Pender’s promotion which was accepted by Lee. Pender found the command to be a heavy burden. He was “an intelligent, reflective man, deeply religious and guided by a strong sense of duty….” [11]

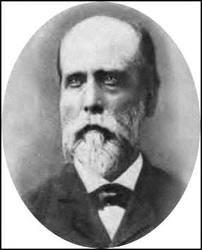

Hill’s second experienced division was that of Major General Richard Anderson, transferred from Longstreet’s First Corps, something else which failed to endear Hill to Longstreet. [12] The unassuming Anderson had distinguished himself as a brigade and division commander in Longstreet’s corps, but in “an army of prima donnas, he was a self-effacing man, neither seeking praise for himself nor winning support by bestowing it on others.” [13] At Chancellorsville he fought admirably and Lee wrote that Anderson was “distinguished for the promptness, courage and skill with which he and his division executed every order.” [14] With four seasoned brigades under excellent commanders it was a good addition to the corps, although the transition from Longstreet’s stolid and cautious style of command to Hill’s impetuous style introduced “another incalculable of the reshuffled army.” [15]

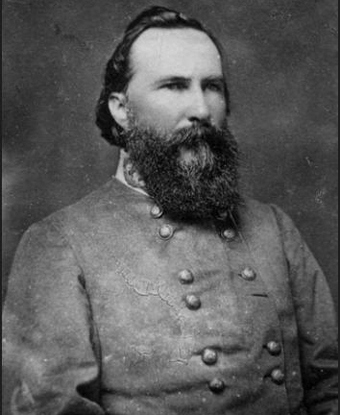

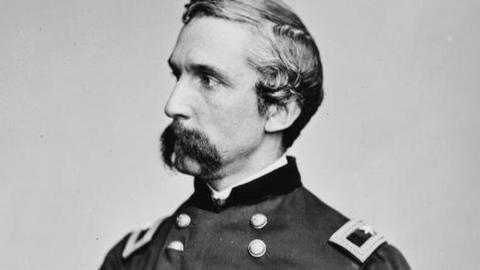

Major General Harry Heth

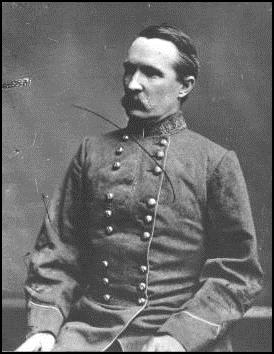

Major General Harry Heth’s division was the final infantry division assigned to the corps. This division was recently formed from two brigades of Hill’s old Light Division and “the two new brigades that Jefferson Davis had forced on an already disrupted army organization.” [16] The organization of this division as well as its leadership would be problematic in the days to come, especially on June 30th and July 1st 1863.

Heth like Pender was also newly promoted to his grade and the action at Gettysburg would be his first test in division command. Heth was a native Virginian, well connected politically who through his social charm had “many friends and bound new acquaintances to him” readily. [17] Heth was a West Point graduate who had an undistinguished academic career graduating last in the class of 1847. His career in the ante-bellum army was typical of many officers, he served “credibly in an 1855 fight with Sioux Indians” but his real claim to fame was in authoring the army’s marksmanship manual which was published in 1858. [18]

Heth’s career with the Confederate army serving in western Virginia was undistinguished but he was a protégé of Robert E. Lee who recommended him as a brigade commander to Jackson before Chancellorsville. Tradition states that of all his generals that Heth was the only one “whom Lee called by his first name.” [19] A.P. Hill when writing Lee about the choice of a successor for the Light Division noted that Heth was “a most excellent officer and gallant soldier” but in the coming campaign “my division under him, will not be half as effective as under Pender.” [20] Douglas Southall Freeman noted that Heth was “doomed to be one of those good soldiers…who consistently have bad luck.” [21]

Heth’s division was composed of two depleted brigades from the Light Division which had taken heavy casualties at Chancellorsville. The brigade commanded by James Archer from Alabama and Mississippi was “well led and had a fine combat reputation.” But the second brigade was more problematic. A Virginia brigade it had once been considered one of the best in the army had deteriorated in quality following the wounding of its first commander Brigadier General Charles Field. Heth took command of it at Chancellorsville and both he and the brigade performed well, but when Heth was promoted the lack of qualified officers left it under the command of its senior colonel, John Brockenbrough. [22] His third brigade came from Mississippi and North Carolina and was commanded by Brigadier General Joe Davis whose uncle was President Jefferson Davis. Davis had served on his uncle’s staff for months and had no combat experience. [23] One author noted that Davis’s promotion to Brigadier General “as unadulterated an instance of nepotism as the record of the Confederacy offers.” [24] His subordinate commanders were no better, one William Magruder was so bad that J.E.B. Stuart suggested that “he have his commission revoked” and only one of the nine field grade officers in his brigade had military training, and that from the Naval Academy. [25]

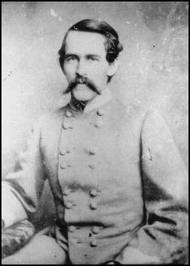

Brigadier General Johnston Pettigrew

Heth’s largest brigade was new to the army. Commanded by the North Carolina academic Johnston Pettigrew it had no combat experience though Pettigrew was considered a strong leader, badly wounded at Seven Pines and thinking his wound mortal “he refused to permit his men to leave the ranks to carry him to the rear” [26] and was captured but later paroled and returned to the army later in the year.

Hill was under the impression that Meade’s army was still miles away, having just come from meeting Lee who assured him that “the enemy are still at Middleburg,” (Maryland) “and have not yet struck their tents.” [27] With that assurance Heth decided to use June 30th to send Pettigrew’s brigade on the foraging expedition to Gettysburg. An officer present noted that Heth instructed Pettigrew “to go to Gettysburg with three of his regiments present…and a number of wagons for the purpose of collecting commissary and quartermaster stores for the use of the army.” [28]

However Heth did instruct Pettigrew in no uncertain terms not to “precipitate a fight” should he encounter “organized troops” of the Army of the Potomac. [29] Heth was specific in his report that “It was told to Pettigrew that he might find in the town in possession of a home guard,…but if, contrary to expectations, he should find any organized troops capable of making resistance., or any part of the Army of the Potomac, he should not attack it.” [30]

That in mind one has to ask the question as to why Heth would employ “so many men on a long, tiring march, especially as without a cavalry escort he took the risk of sending them into a trap” when his “objects hardly justified” using such a large force. [31] Likewise it has to be asked why the next day in light of Lee’s standing orders not to provoke an engagement that Hill would send two divisions, two thirds of his corps on a reconnaissance mission. Some have said that Hill would have had to move to Gettysburg on July 1st anyway due to forage needs of the army, [32] but this is not indicated in any of Hill or Heth’s reports.

As his troops neared Gettysburg Pettigrew observed the Federal cavalry of Buford’s 1st Cavalry Division as they neared the town. He received another report “indicating that drumming could be heard in the distance – which might mean infantry nearby, since generally cavalry generally used only bugles.” [33] He then prudently and in accordance with his orders not to precipitate a fight “elected to withdraw rather than risk battle with a foe of unknown size and composition.” [34] His troops began their retrograde at 11 a.m. leaving Buford’s cavalry to occupy the town at ridges. On Confederate wrote “in coming in contact with the enemy, had quite a little brush, but being under orders not to bring a general engagement fell back, followed by the enemy.” [35]

Upon returning Pettigrew told Hill and Heth that “he was sure that the force occupying Gettysburg was a part of the Army of the Potomac” but Hill and Heth discounted Pettigrew’s report. [36] “Heth did not think highly of such wariness” and “Hill agreed with Heth” [37] Hill believed that nothing was in Gettysburg “except possibly a cavalry vidette.” [38] Hill was not persuaded by Pettigrew or Pettigrew’s aide Lieutenant Louis Young who had previously served under Hill and Pender who reported that the “troops that he saw were veterans rather than Home Guards.” [39] Hill reiterated that he did not believe “that any portion of the Army of the Potomac was up” but then according to Young Hill “expressed the hope that it was, as this was the place he wanted it to be.” [40] The West Point Graduates Hill and Heth may have manifested an often typical “distain for citizen soldiers…a professional questioning a talented amateur’s observations” [41] If so it was a distain that would cost the Confederacy dearly in the days to come.

Pettigrew was “aghast at Hill’s nonchalant attitude” [42] and Young was dismayed and later recalled that “a spirit of unbelief” seemed to cloud their thinking. [43] In later years he wrote “blindness in part seems to have come over our commanders, who slow to believe in the presence of an organized army of the enemy, thought that there must be a mistake in the report taken back by General Pettigrew.” [44]

Heth then asked Hill since neither believed Pettigrew’s report “whether Hill would have any objection to taking his division to Gettysburg again to get those shoes. Hill replied “none in the world.” [45] Douglas Southall Freeman wrote “On those four words fate hung” [46] and then, in “that incautious spirit, Hill launched Harry Heth’s division down the Chambersburg Pike and into battle at Gettysburg.” [47]

Notes

[1] Napoleon Bonaparte, Military Maxims of Napoleon in Roots of Strategy: The Five Greatest Military Classics of All Time edited by Phillips, Thomas R Stackpole Books Mechanicsburg PA 1985 p.410

[2] Coddinton, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command A Touchstone Book, Simon and Shuster New York 1968 p.194

[3] Ibid. Coddinton, The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p. 263

[4] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a NationKnopf, New York 1958 p.81

[5] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command, One volume abridgement by Stephen W Sears, Scribner, New York 1998 p.460

[6] Sears, Stephen W. Chancellorsville A Mariner Book, Houghton and Mifflin Company, Boston and New York 1996 p.51

[7] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.453

[8] Ibid. Dowdy, Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.79

[9] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.109

[10] Ibid. Dowdy, Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.88

[11] Ibid. Dowdy, Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.85

[12] Ibid. Dowdy, Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.86

[13] Ibid. Dowdy, Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.86

[14] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.512

[15] Ibid. Dowdy, Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.86

[16] Ibid. Dowdy, Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.87

[17] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.527

[18] Krick, Robert K. Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge: Failures of Brigade Leadership on the First Day of Gettysburg in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.96

[19] Ibid. Krick. Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.96

[20] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.527

[21] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.46

[22] Ibid. Dowdy, Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation p.87

[23] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.533

[24] Ibid. Krick. Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.99

[25] Ibid. Krick. Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.101

[26] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p.136

[27] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.131

[28] Tredeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.128

[29] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.136

[30] Ibid. Tredeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.129

[31] Ibid. Coddinton,. The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p. 263

[32] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.131 This argument does have merit based on the considerations Guelzo lists but neither Hill, Heth or Lee make any mention of that need in their post battle reports.

[33] Ibid. Tredeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.130

[34] Gallagher, Gary. Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg: A.P. Hill and Richard S. Ewell in a Difficult Debut in The First Day at Gettysburg edited by Gallagher, Gary W. Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 1992 p.42

[35] Ibid. Tredeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.135

[36] Ibid. Coddinton, The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command pp. 263-264

[37] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.465

[38] Pfanz Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001 p.27

[39] Ibid. Gallagher, Gary. Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.42

[40] Ibid. Pfanz. Gettysburg: The First Day p.27

[41] Ibid. Gallagher, Gary. Confederate Corps Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg p.42

[42] Ibid. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.131

[43] Ibid. Coddinton, The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p. 264

[44] Ibid Pfanz Gettysburg: The First Day p.27

[45] Ibid. Coddinton, The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command p. 264

[46] Ibid. Freeman Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command p. 563

[47] Ibid. Krick. Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge p.94