Friends of Padre Steve’s World

This is part one of a very long chapter in my Gettysburg Staff Ride Text. The chapter is different because instead of simply studying the battle my students also get some very detailed history about the ideological components of war that helped make the American Civil War not only a definitive event in our history; but a war of utmost brutality in which religion drove people and leaders on both sides to advocate not just defeating their opponent, but exterminating them.

But the study of this religious and ideological war is timeless, for it helps us to understand the ideology of current rivals and opponents, some of whom we are in engaged in battle and others who we spar with by other means, nations, tribes and peoples whose world view, and response to the United States and the West, is dictated by their religion.

Yet for those more interested in current American political and social issues the period is very instructive, for the religious, ideological and political arguments used by Evangelical Christians in the ante-bellum period, as well as many of the attitudes displayed by Christians in the North and the South are still on display in our current political and social debates.

I will be posting the next two parts over the next two days.

Peace

Padre Steve+

“At length on 12th April, the tension could no longer bear the strain. Contrary to instructions, in the morning twilight, and when none could see clearly what the historic day portended, the Confederates in Charleston bombarded Fort Sumter, and the thunder of their guns announced that the argument of a generation should be decided by the ordeal of war. A war, not between two antagonistic political parties, but a struggle to the death between two societies, each championing a different civilization…” 1

War cannot be separated from Ideology, Politics or Religion One can never separate war and the means by which it is fought from its political ends. According to Clausewitz war is an extension or continuation of politics. Of course Clausewitz understood the term politics or policy in the light of the concept of a “World View” or to use the German term Weltungschauung. The term is not limited to doctrine or party politics, but it encompasses the world view of a people or culture. The world view is oft used by the political, media and religious leadership of countries and can be quite instrumental in the decision by a people to go to war; who they war against, their reasons for going to war, the means by which they fight the war, and the end state that they envision. This concept includes racial, religious, cultural, economic and social dimensions of a world view.

One of the problems that modern Americans and Western Europeans have is that we tend to look at the world, particularly in terms of politics and policy, be it foreign or domestic, through a prism from which we cannot see the forest for the trees. We look at individual components of issues such as economic factors, military capabilities, existing political systems, diplomatic considerations and the way societies get information in isolation from each other. We dissect them, we analyze them, and we do a very good job in examining and evaluating each individual component; but we often do this without understanding the world view and ideological factors that link how a particular people, nation or party understand these components of policy.

Likewise policy makers tend to take any information they receive and interpret it through their own world view. This is true even if they have no idea what their world-view is or how they came to it. Most often a world view is absorbed over years. Barbara Tuchman wrote that “When information is relayed to policy-makers, they respond in terms of what is already inside their heads and consequently make policy less to fit the facts than to fit the notions and intentions formed out of the mental baggage that has accumulated in their minds since childhood.” 2

Policy makers often fail to see just how interconnected the most primal elements of the human experience are to the world view of others as well as their own.

Because of this many policy makers, be they military or civilian do not understand how critical the understanding of world view to designing effective polices. Likewise many fail to see how the world view of others influences their application of economic, political, diplomatic and military power as well as the use and dissemination of information in their nation or culture. This is true no matter which religion or sect is involved, even if a people or nation is decidedly secular, and at least outwardly non-religious.

Perhaps this is because we do not want to admit that our Western culture itself is very much a product of primal religious beliefs which informed politics, philosophy, ethics, law, economics, views of race, and even the arts for nearly two millennia. Perhaps it is because we are justifiably appalled and maybe even embarrassed at the excesses and brutality of our ancestors in using religion to incite the faithful to war; to use race and religion justification to subjugate or exterminate peoples that they found to be less than human; or to punish and conquer heretics.

The United States Military made a belated attempt to address ideology, culture and religion in terms of counter-insurgency doctrine when it published the U.S. Army/Marine Counterinsurgency Manual. The discussion of these issues is limited to two pages that specifically deal with various extreme Moslem groups that use that religion as a pillar of their ideology, strategy and operations. But the analysis in the counterinsurgency manual of is limited because its focus is very general and focused at a tactical level.

Likewise the analysis of world view, ideology and religion in the counterinsurgency manual is done in a manner of “us versus them” and though it encourages leaders to attempt to understand the cultural differences there is little in it to help leaders to understand who to do this. Commendably the manual discusses how terrorist and insurgent groups use ideology, frequently based on religion to create a narrative. The narrative often involves a significant amount of myth presented as history, such as how Al Qaida and ISIL using the Caliphate as a religious and political ideal to strive to achieve, because for many Moslems “produces a positive image of the golden age of Islamic civilization.” 3 However, we frequently cannot see how Americans have used, and in some cases continue to the Puritan understanding of a city set on a hill which undergirded Manifest Destiny, the extermination of Native Americans, the War with Mexico, the romanticism of the ante-bellum South and later the Lost Cause.

Policy makers and military leaders must realize that if they want to understand how culture and religious ideology drive others to conquer, subjugate and terrorize in the name of God, they first have to understand how our ancestors did the same thing. It is only when they do that that they can understand that this behavior and use of ideology for such ends is much more universal and easier to understand.

If one wants to see how the use of this compulsion to conquer in the name of God in American by a national leader one needs to go no farther than to examine the process whereby President McKinley, himself a veteran of the Civil War, decided to annex the Philippine in 1898 following the defeat of the Spanish. That war against the Filipinos that we had helped liberate from Spanish rule saw some of the most bloodthirsty tactics employed in fighting the Filipino insurgents, who merely wanted independence. It was a stain on our national honor which of which Mark Twain wrote: “There must be two Americas: one that sets the captive free, and one that takes a once-captive’s new freedom away from him, and picks a quarrel with him with nothing to found it on; then kills him to get his land. . .

A Doubtlessly sincere McKinley sought counsel from God about whether he should annex the the Philippines or not.

“He went down on his knees, according to his own account, and “prayed to Almighty God for light and guidance.” He was accordingly guided to conclude “that there was nothing left to do for us but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos. And uplift and civilize and Christianize them, by God’s grace to do the very best we could by them, as our fellowmen for whom Christ died.” 4

On the positive side the counterinsurgency manual does mention how “Ideology provides a prism, including a vocabulary and analytical categories, through which followers perceive their situation.” 5 But again it does so at a micro-level and the lessons of it are not applied at the higher levels of strategic thinking and policy.

Thus when faced with cultures for which religion provides the adhesive which binds each of these elements, such as the Islamic State or ISIL we attempt to deal with each element separately, as if they have no connection to each other. But that is where we err, for even if the religious cause or belief has little grounding in fact, science or logic, and may be the result of a cultures attempting to seize upon mythology to build a new reality, it is, in the words of Reggie Jackson the “straw that stirs the drink” and to ignore or minimize it is to doom our efforts to combat its proponents.

Perhaps that is because we do not like to look at ourselves and our own history in the mirror. Perhaps it is because we are uncomfortable with the fact that the face that we see in the mirror is face too similar to those we oppose who are perfectly willing to commit genocide in the name of their God, than we want to admit. Whether this is because we are now predominantly secularist in the way that we do life, or because we are embarrassed by the religiously motivated actions of our forefathers, the result is strikingly and tragically similar.

Clausewitz was a product of classic German Liberalism. He understood the effects of the moral and spiritual concerns inherent in policy, and it flows from his pen, as where he wrote “that the aim of policy is to unify and reconcile all aspects of internal administration as well as of spiritual values, and whatever else the moral philosopher may care to add.” 6 Clausewitz understood that when the motivation behind politics becomes more extreme and powerful; when the politics becomes more than a simple disagreement about isolated policy issues; when the ideology that lays behind the politics, especially ideology rooted in religion evokes primal hatred between peoples, war can come close to reaching the abstract concept of absolute or total war.

Clausewitz wrote:

“The more powerful and inspiring the motives for war, the more they affect the belligerent nations and the fiercer the tensions that precede the outbreak, the closer will war approach its abstract concept, the more important will be the destruction of the enemy, the more closely will the military and the political objects of war coincide, and the more military and less political will war appear to be….” 7

The American Civil War was the first modern war based on the advancement of technology and the changing character of war. But it was also a modern war which reached back to the most primal urges of the people involved, including the primal expressions of religious justification for their actions that both sides accepted as normal.

The American Civil War was caused by the clash of radically different ideologies, ideologies which championed two very different views of civilization, government, economics and the rights of people. However, these different world views were based based upon a common religious understanding:

“whatever their differences over such matters as slavery and political preaching, both sides read their Bibles in remarkably similar ways Ministers had long seen the American republic as a new Israel, and Confederate preachers viewed the southern nation in roughly the same light. The relentless, often careless application of biblical typologies to national problems, the ransacking of scripture for parallels between ancient and modern events produced a nationalistic theology at once bizarre, inspiring and dangerous. Favorite scripture passages offered meaning and hope to a people in the darkest hours and, at the same time, justified remorseless bloodshed.” 8

This understanding manifested itself in each side’s appeal to their Puritan ancestor’s concept of a “city set on a hill,” a mantle that each side claimed to be the legitimate heir. Though they seem radically different, they are actually two sides of the same religious-ideological coin.

The American Civil War was a religious and ideological war. “Like the total wars of the twentieth century, it was preceded by years of violent propaganda, which long before the war had obliterated all sense of moderation, and had awakened in the contending parties the primitive spirit of tribal fanaticism.” 9 It was preceded by the fracturing of political parties and alliances which had worked for compromise in the previous decades to preserve the Union even at the cost of maintaining slavery.

Far from being irrational as some have posited, the actions and behavior of politicians in both the North and the South was completely rational based on their conflicting ideologies and views of their opponents. The “South’s fears of territorial and economic strangulation and the North’s fears of a “slave power” conspiracy are anything but irrational, and only someone who refuses to think through the evidence available to Americans in the 1850s would find either of them at all illogical.” 10

Understanding How Religiously Based Ideology influences Policy, Politics and War Samuel Huntington wrote:

“Blood, language, religion, way of life were what the Greeks had in common and what distinguished them from the Persians and other non-Greeks. Of all the objective elements which define civilizations, however, the most important is usually religion, as the Athenians emphasized. To a very large degree, the major civilizations in human history have been closely identified with the world’s great religions; and who share ethnicity and language but differ in religion may slaughter each other…” 11

The very realistic fears of both sides brought about clash of extremes in politics which defied efforts at compromise and was already resulting in violent and bloody conflicts between ideologues in Kansas, Missouri and Kentucky years before the firing on Fort Sumter. For both sides their views became a moral cause that in the minds of many became an article of their religious faith, and “Religious faith itself became a key part of the war’s unfolding story for countless Americans….” 12 British theorist and military historian J.F.C. Fuller wrote of the religious undergirding of the war:

“As a moral issue, the dispute acquired a religious significance, state rights becoming wrapped up in a politico-mysticism, which defying definition, could be argued for ever without any hope of a final conclusion being reached.” 13

That is why it impossible to simply examine the military campaigns and battles of the Civil War in isolation from the politics, polices, the competing philosophies and the underlying theology which were the worldview that undergirded the arguments of both sides. Those competing philosophies and world views, undergirded by a pervasive nationalistic understanding of religion not only helped to cause on the war but made the war a total war.

Some might wonder where this fits in a text that is about a specific campaign and battle in a war, but for those entrusted with planning national defense and conducting military campaign the understanding of why wars are fought, in particular the ideological causes of war matter in ways that military planners, commanders and even elected political leadership often overlook. Colin Gray notes: “Wars are not free floating events, sufficient unto themselves as objects for study and understanding. Instead, they are entirely the product of their contexts.” 14

Studying the context of the American Civil War is very important in understanding not just it, but also civil wars in other nations which are currently raging. The study of these contexts brings an American or Western historical perspective to those wars, not so much in trying to place a western template over non-western conflicts; but a human perspective from our own past from which we can gain insight into how the people, even people who share a common language, religion and history, can war against each other in the most brutal of fashions. Again I refer to Colin Gray who noted “Policy and strategy will be influenced by the cultural preferences bequeathed by a community’s interpretation of its history as well as by its geopolitical-geostrategic context.” 15

For American and other Western political and military policy makers this is particularly important in Iraq where so many Americans have fought, and in the related civil war in Syria which has brought about the emergence of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

Likewise in our Western tradition we can see how radical ideology, based on race was central to Hitler’s conduct of war, especially in the East during the Second World War. Hitler’s ideology permeated German military campaigns and administration of the areas conquered by his armies. No branch of the German military, police or civil administration in occupied Poland or Russia was exempt guiltless in the crimes committed by the Nazi regime. It is a chilling warning of the consequences awaiting any nation that allows it to become caught up in hate-filled political, racial or even religious ideologies which dehumanizes opponents and of the tragedy that awaits them and the world. In Germany the internal and external checks that govern the moral behavior of the nation and individuals failed. Caught up in the Nazi system, the Germans, especially the police and military abandoned the norms of international law, morality and decency, banally committing crimes which still reverberate today and which are seen in the ethnic cleansing actions in the former Yugoslavia and other European nations.

Thus the study of the American Civil War, from the cultural, economic, social and religious differences which divided the nation helps us in understanding war. But even more importantly we have to understand the ideological clash between Abolitionists in the North, and Southern proponents of slavery. Both the ideologies of the Abolitionists who believed that African Americans were created by God and had the same rights as whites, as well as the Southern arguments that blacks were inferior and slavery was a positive good, were buttressed by profoundly religious arguments related directly to a divergence in values. It was in this “conflict of values, rather than a conflict of interests or a conflict of cultures, lay at the root of the sectional schism.” 16

Understanding this component of our own nation’s history helps us to understand how those same factors influence the politics, policies, the primal passions and hatreds of people in other parts of the world. Thus they are helpful for us to understand when we as a nation involve ourselves in the affairs of other peoples whose conflicts are rooted in religiously motivated ideology and differences in values, such as in the current Sunni-Shia conflict raging in various guises throughout the Middle East where culture, ideology and economic motivations of the groups involved cannot be separated. We may want to neatly separate economic, strategic, military and geopolitical factors from religious or ideological factors assuming that each exists in some sort of hermetically sealed environment. But to think this is a fallacy of the greatest magnitude. As we have learned too late in the century in our Middle East muddling, it is impossible to separate geopolitical, strategic, military and economic issues from ideological issues rooted in distinctly religious world views, world views that dictate a nation, people or culture’s understanding of the world.

David M. Potter summed up this understanding of the connection between the ideological, cultural and economic aspects and how the issue of slavery connected all three realms in the American Civil War:

“These three explanations – cultural, economic and ideological – have long been the standard formulas for explaining the sectional conflict. Each has been defended as though it were necessarily incompatible with the other two. But culture, economic interest, and values may all reflect the same fundamental forces at work in a society, in which case each will appear as an aspect of the other. Diversity of culture may produce both diversity of interests and diversity of values. Further, the differences between a slaveholding and a nonslaveholding society would be reflected in all three aspects. Slavery represented an inescapable ethical question which precipitated a sharp conflict of values.” 17

The Impact of Slavery on the Growing Divide between North and South

The political ends of the Civil War came out of the growing cultural, economic, ideological and religious differences between the North and South that had been widening since the 1830s. However, slavery was the one issue which helped produce this conflict in values and it was “basic to the cultural divergence of the North and South, because it was inextricably fused into the key elements of southern life – the staple crop of the plantation system, the social and political ascendency of the planter class, the authoritarian system of social control.” 18 Without slavery and the southern commitment to an economy based on slave labor, the southern economy would have most likely undergone a similar transformation as what happened in the North; thus the economic divergence between North and South would “been less clear cut, and would have not met in such head-on collision.” 19 But slavery was much more than an economic policy for Southerners; it was a key component of their religious, racial and philosophic world view.

The issue of slavery even divided the ante-Bellum United States on what the words freedom and liberty meant, the dispute can be seen in the writings of many before the war, with each side emphasizing their particular understanding of these concepts. Many Southerners, including poor whites saw slavery as the guarantee of their economic freedom. John C. Calhoun said to the Senate in 1848 that “With us, the two great divisions of society are not the rich and poor, but white and black; and all of the former, the poor as well as the rich, belong to the upper class, and are respected and treated as equals.” 20

But it was Abraham Lincoln who cut to the heart of the matter when he noted that “We all declare for liberty” but:

“in using the same word we do not all mean the same thing. With some the word liberty may mean for each man to do as he pleases with himself and the product of his labor; while with others the same word may mean for some men to do as they please with other men and the product of other men’s labor.” 21

The growing economic disparity between the Slave and Free states became more about the expansion of slavery in federal territories as disunion and war approached; for a number of often competing reasons. These differences were amplified by the issue of slavery led to the substitution of stereotypes of each other and had the “effect of changing men’s attitudes toward the disagreements which are always certain to arise in politics: ordinary, resolvable disputes were converted into questions of principle, involving rigid, unnegotiable dogma.” 22 The editor of the Charleston Mercury noted in 1858 that “on the subject of slavery…the North and the South…are not only two peoples, but they are rival, hostile peoples.” 23

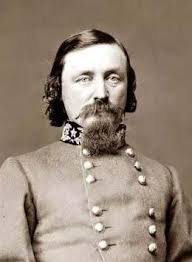

This was driven both by the South’s insistence on both maintaining slavery where it was already legal and expanding it into new territories which was set against the vocal abolitionist movement. They were also fighting an even more powerful enemy, Northern industrialists who were not so idealistic, and much more concerned with “economic policy designed to secure Northern domination of Western lands than the initial step in a broad plan to end slavery.” 24 This completion between the regions not only affected politics, it affected religion and culture In the South it produced a growing culture of victimhood which is manifest in the words of Robert Toombs who authored Georgia’s declaration of causes for secession:

“For twenty years past, the Abolitionists and their allies in the Northern states, have been engaged in constant efforts to subvert our institutions, and to excite insurrection and servile war among us…” whose “avowed purpose is to subject our society, subject us, not only to the loss of our property but the destruction of ourselves, our wives and our children, and the dissolution of our homes, our altars, and our firesides.” 25

As the differences grew and tensions rose the South became ever more closed off from the North. “More than other Americans, Southerners developed a sectional identity outside the national mainstream. The Southern life style tended to contradict the national norm in ways that life styles of other sections did not.” 26

The complex relationship of Southern society where the “Southern bodies social, economic, intellectual, and political were decidedly commingled” 27 and politics of the South came more to embrace the need for slavery and its importance, even to poor whites in the South who it did not benefit and actually harmed economically: “the system of subordination reached out still further to require a certain kind of society, one in which certain questions were not publically discussed. It must give blacks no hope of cultivating dissention among the whites. It must commit non slaveholders to the unquestioning support of racial subordination….In short, the South became increasingly a closed society, distrustful of isms from outside and unsympathetic to dissenters. Such were the pervasive consequences of giving top priority to the maintenance of a system of racial subordination.” 28

Southern planters declared war on all critics of their “particular institution” beginning in the 1820s. As Northern abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and his newspaper The Liberator grew in its distribution and began to appear in the South various elected officials throughout the South “suppressed antislavery books, newspapers, lectures, and sermons and strove generally to deny critics of bondage access to any public forum.” 29

In response to the proliferation of abolitionist literature in the South, John C. Calhoun proposed that Congress pass a law to prosecute “any postmaster who would “knowingly receive or put into the mail any pamphlet, newspaper, handbill, or any printed, written, or pictorial representation touching the subject of slavery.” 30 Calhoun was not alone as other members of Congress as well as state legislatures worked to restrict the import of what they considered subversive and dangerous literature.

Beginning in 1836 the House of Representatives passed a “gag rule” for its members which “banned all petitions, memorials, resolutions, propositions, or papers related in any way or to any extent whatever to the subject of slavery.” 31 This was challenged by former President John Quincy Adams in 1842 as well as by others so that in 1844 the House voted to rescind it. However Southern politicians “began to spout demands that the federal government and the Northern states issue assurances that the abolitionists would never be allowed to tamper with what John Calhoun had described as the South’s “peculiar domestic institution.” 32 The issue of slavery more than any other “transformed political action from a process of accommodation to a mode of combat.” 33

Around the same time as the gag rule was played out in Congress the Supreme Court had ruled that the Federal government alone “had jurisdiction where escaped slaves were concerned” which resulted in several states enacting “personal liberty laws” to “forbid their own elected officials from those pursuing fugitives.” Southern politicians at the federal and state levels reacted strongly to these moves which they believed to be an assault on their institutions and their rights to their human property. Virginia legislators protested that these laws were a “disgusting and revolting exhibition of faithless and unconstitutional legislation.” 34

The issue of slavery shaped political debate and “structured and polarized many random, unoriented points of conflict on which sectional interest diverged.” 35 As the divide grew leaders and people in both the North and the South began to react to the most distorted images of each other imaginable- “the North to an image of a southern world of lascivious and sadistic slave drivers; the South to the image of a northern world of cunning Yankee traders and radical abolitionists plotting slave insurrections.” 36

The Slaveholder Ideology Personified: Edmund Ruffin

Among the people most enraged by Northern opposition to slavery was Edmund Ruffin. Ruffin was a very successful farm paper editor, plantation owner and ardent old line secessionist from Virginia. In 1860 the then 67 year old Ruffin helped change the world forever when, according to popular legend he pulled the lanyard which fired the first shot at Fort Sumter. While he was there and probably was given the honor of firing the first shot from his battery; other guns from other emplacements may have fired first. 37

Ruffin was a radical ideologue, he had been passionately arguing for secession and Southern independence for fifteen years. Ruffin “perceived the planter civilization of the South in peril; the source of the peril was “Yankee” and union with “Yankees.” Thus he preached revolution, Ruffin was a rebel with a cause, a secular prophet…” 38 He was a type of man who understood reality far better than some of the more moderate oligarchs that populated the Southern political and social elite. While in the years leading up to the war these men, including John Calhoun attempted to secure the continued existence and spread of slavery within the Union through the Congress and the courts, as early as 1850, Ruffin recognized that in order for slavery to survive the slaveholding South would have to secede from the Union. Ruffin and other radical secessionists believed that there could be no compromise with the north. In 1850 he and James Hammond attempted to use a meeting in Nashville to “secure Cooperative State Secession” and wrote to Hammond, against those who sought to use the meeting to preserve the Union, “If the Convention does not open the way to dissolution…I hope it shall never meet.” 39 He believed that in order to maintain the institution of slavery the slave holding states that those states had to be independent from the North.

Ruffin’s views were not unique to him, the formed the basis of how most slave owners and supporters felt about slavery’s economic benefits, Ruffin wrote:

“Still, even this worst and least profitable kind of slavery (the subjection of equals and men of the same race with their masters) served as the foundation and the essential first cause of all the civilization and refinement, and improvement of arts and learning, that distinguished the oldest nations. Except where the special Providence and care of God may have interposed to guard a particular family and its descendants, there was nothing but the existence of slavery to prevent any race or society in a state of nature from sinking into the rudest barbarism. And no people could ever have been raised from that low condition without the aid and operation of slavery, either by some individuals of the community being enslaved, by conquest and subjugation, in some form, to a foreign and more enlightened people.”40

Slavery and National Expansion: The Compromise of 1850

The Ante-Bellum South was an agrarian society which depended on the free labor provided by slaves and in a socio-political sense it was an oligarchy that offered no freedom to slaves, openly discriminated against free blacks and provided little hope of social or economic advancement for poor and middle class whites, but it was maintained because in many cases the Southern Yeoman farmer “feared the fall from independent producer to dependent proletarian, a status he equated with enslavement.” 41 But northerners often driven by religious understandings of human rights founded in the concept of a higher law over a period of a few decades abolished slavery in the years after the United States had gained independence.

However, the South had tied its economy and society to the institution of slavery, and was not content to see it remain just in the original states of the Old South.

The expansion of slavery was essential to its continued maintenance in the states where it was already legal. “Because of the need to maintain a balance in the Senate, check unruly slaves, and cultivate fertile soils, many planters and small plantation owners- particularly those living in the southern districts of the cotton states- asserted that their survival depended on new territory.” 42 In those decades “a huge involuntary migration took place. Between 800,000 and 1 million slaves were moved westward….” 43

The need for slaves caused prices to soar. In some older states like Virginia where fewer slaves were required the exportation of slaves became a major industry:

“male slaves were marched in coffles of forty or fifty, handcuffed to each other in pairs, with a long chain through the handcuffs passing down the column to keep it together, closely guarded by mounted slave traders followed by an equal number of female slaves and their children. Most of them were taken to Wheeling, Virginia, the “busiest slave port” in the United States, and from there they were transported by steamboat to New Orleans, Natchez, and Memphis.” 44

In the years the before the war, the North embraced the Industrial Revolution leading to advances which gave it a marked economic advantage over the South in which through its “commitment to the use of slave labor inhibited economic diversification and industrialization and strengthened the tyranny of King Cotton.” 45 The population of the North also expanded at a clip that far outpaced the South as European immigrants swelled the population.

The divide was not helped by the various compromises worked out between northern and southern legislators. After the Missouri Compromise Thomas Jefferson wrote:

“but this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. It is hushed indeed for the moment, but this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.” 46

The trigger for the increase in tensions was the war with Mexico in which the United States annexed nearly half of Mexico.

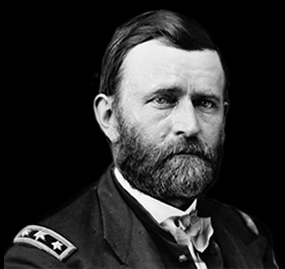

The new territories were viewed by those who advocated the expansion of slavery as fresh and fertile ground for its spread. Ulysses S Grant, who served in the war, noted the effects of the war with Mexico in his memoirs:

“In taking military possession of Texas after annexation, the army of occupation, under General [Zachary] Taylor, was directed to occupy the disputed territory. The army did not stop at the Nueces and offer to negotiate for a settlement of the boundary question, but went beyond, apparently in order to force Mexico to initiate war….To us it was an empire and of incalculable value; but it might have been obtained by other means. The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war.”47

Robert Toombs of Georgia was an advocate for the expansion of slavery into the lands conquered during the war. Toombs warned his colleagues in Congress “in the presence of the living God, that if you by your legislation you seek to drive us from the territories of California and New Mexico, purchased by the common blood and treasure of the whole people…thereby attempting to fix a national degradation upon half the states of this Confederacy, I am for disunion.” 48

The tensions in the aftermath of the war with Mexico escalated over the issue of slavery in the newly conquered territories brought heated calls by some southerners for secession and disunion. To preserve the Union, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, supported by the new President Millard Fillmore were able to pass the compromise of 1850 solved a number of issues related to the admission of California to the Union and boundary disputes involving Texas and the new territories. But among the bills that were contained in it was the Fugitive Slave Law, or The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The act was the devise of Henry Clay which was meant to sweeten the deal for southerners. The law would “give slaveholders broader powers to stop the flow of runaway slaves northward to the free states, and offered a final resolution denying that Congress had any authority to regulate the interstate slave trade.” 49 which for all practical purposes nationalized the institution of slavery, even in Free states by forcing all citizens to assist law enforcement in apprehending fugitive slaves and voided state laws in Massachusetts, Vermont, Ohio, Connecticut, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island which barred state officials from aiding in the capture, arrest or imprisonment of fugitive slaves. “Congress’s law had nationalized slavery. No black person was safe on American soil. The old division of free state/slave state had vanished….” 50

That law required all Federal law enforcement officials, even in non-slave states to arrest fugitive slaves and anyone who assisted them, and threatened law enforcement officials with punishment if they failed to enforce the law. The law stipulated that should “any marshal or deputy marshal refuse to receive such warrant, or other process, when tendered, or to use all proper means diligently to execute the same, he shall, on conviction thereof, be fined in the sum of one thousand dollars.” 51

Likewise the act compelled citizens in Free states to “aid and assist in the prompt and efficient execution of this law, whenever their services may be required….” 52 Penalties were harsh and financial incentives for compliance attractive.

“Anyone caught providing food and shelter to an escaped slave, assuming northern whites could discern who was a runaway, would be subject to a fine of one thousand dollars and six months in prison. The law also suspended habeas corpus and the right to trial by jury for captured blacks. Judges received a hundred dollars for every slave returned to his or her owner, providing a monetary incentive for jurists to rule in favor of slave catchers.” 53

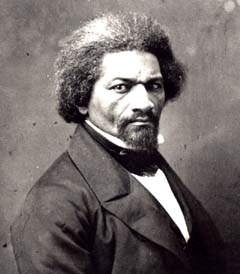

The law gave no protection for even black freedmen. No proof or evidence other than the sworn statement of the owner that a black was or had been his property was required to return any black to slavery. Frederick Douglass said:

“By an act of the American Congress…slavery has been nationalized in its most horrible and revolting form. By that act, Mason & Dixon’s line has been obliterated;…and the power to hold, hunt, and sell men, women, and children remains no longer a mere state institution, but is now an institution of the whole United States.” 54

On his deathbed Henry Clay praised the act, which he wrote “The new fugitive slave law, I believe, kept the South in the Union in ‘fifty and ‘fifty-one. Not only does it deny fugitives trial by jury and the right to testify; it also imposes a fine and imprisonment upon any citizen found guilty of preventing a fugitive’s arrest…” Likewise Clay depreciated the opposition noting “Yes, since the passage of the compromise, the abolitionists and free coloreds of the North have howled in protest and viciously assailed me, and twice in Boston there has been a failure to execute the law, which shocks and astounds me…. But such people belong to the lunatic fringe. The vast majority of Americans, North and South, support our handiwork, the great compromise that pulled the nation back from the brink.” 55

To be continued tomorrow….

Notes

1 Fuller, J.F.C. The Conduct of War 1789-1961 Da Capo Press, New York 1992. Originally published by Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick N.J p.98

2 Tuchman, Barbara W. Practicing History Alfred A. Knopf, New Your 1981 p.289

3 ___________ U.S. Army/ Marine Counterinsurgency Field Manual FM 3-24 MCWP 3-33.5 15 December 2006 with and forward by General David A Petreus and General James Amos, Konecky and Konecky, Old Saybrook CT 2007 p.26

4 Ibid. Tuchman Practicing History p.289

5 Ibid. U.S. Army/ Marine Counterinsurgency Field Manual p.27

6 Clausewitz, Carl von On War Indexed edition, edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1976 p.606

7 Ibid. Clausewitz On War pp.87-88

8 Rable, George C. God’s Almost Chosen Peoples: A Religious History of the American Civil War University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 2010 p.4

9 Ibid. Fuller The Conduct of War 1789-1961 p.99

10 Guelzo Allen C. Fateful Lightening: A New History of the Civil War Era and Reconstruction Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2012 p.95

11 Huntington, Samuel P. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order Touchstone Books, New York 1997 p.42

12 Ibid. Rable God’s Almost Chosen Peoples p.5

13 Fuller, J.F.C. Decisive Battles of the U.S.A. 1776-1918 University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln 2007 copyright 1942 The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals p.174

14 Gray, Colin S. Fighting Talk: Forty Maxims on War, Peace, and Strategy Potomac Books, Dulles VA 2009 p.3

15 Ibid. Gray Fighting Talk p.25

16 Potter, David M. The Impending Crisis: America before the Civil War 1848-1861 completed and edited by Don E. Fehrenbacher Harper Collins Publishers, New York 1976 p.41

17 Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.41

18 Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.42

19 Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.42

20 McPherson, James M. Drawn With the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1996 p.50

21 Levine, Bruce Half Slave and Half Free: The Roots of the Civil War Revised Edition, Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York 1992 and 1995 p.122

22 Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.43

23 Ibid. McPherson Drawn With the Sword p.16

24 Egnal, Marc Clash of Extremes: The Economic Origins of the Civil War Hill and Wang a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux New York 2009 p.6

25 Dew, Charles B. Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville and London 2001 p.12

26 Thomas, Emory The Confederate Nation 1861-1865 Harper Perennial, New York and London 1979 p.5

27 Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation p.5

28 Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis pp.457-458

29 Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free p.166

30 Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening pp.50-51

31 Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free pp.169-170

32 Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening pp.51-52

33 Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.43

34 Ibid. Levine Half Slave and Half Free pp.169-170

35 Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.43

36 Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.43

37 Catton, Bruce The Coming Fury Phoenix Press, London 1961 pp.314-315

38 Ibid. Thomas The Confederate Nation p.1

39 Freehling, William W. The Road to Disunion Volume One: Secessionists at Bay Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1990 p.481

40 Ruffin, Edmund The Political Economy of Slavery in McKitrick, Eric L. ed. Slavery Defended: The Views of the Old South. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall/Spectrum Books, 1963.Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/primary-resources/lincolns-political-economy/ 24 March 2014

41 Ibid. McPherson Drawn With the Sword p.50

42 Ibid. Egnal Clash of Extremes pp.125-126

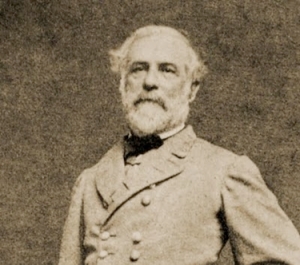

43 Korda, Michael. Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2014 p.203

44 Ibid. Korda Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee p.203

45 Ibid. Potter The Impending Crisis p.42

46 Jefferson, Thomas Letter to John Holmes dated April 22nd 1824 retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/159.html 24 March 2014

47 U.S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant New York 1885 pp.243-245

48 Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening pp.62-63

49 Ibid. Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.68

50 Goldfield, David America Aflame: How the Civil War Created a Nation Bloomsbury Press, New York, London New Delhi and Sidney 2011 p.71

51 ______________Fugitive Slave of Act 1850 retrieved from the Avalon Project, Yale School of Law http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/fugitive.asp 11 December 2014

52 Ibid. Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

53 Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.71

54 Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.72

55 Ibid. Oates The Approaching Fury p.94