Friends of Padre Steve’s World

Here is the latest chapter revision of my Gettysburg text. It is long but again a complex subject that does with more than just the battle. It deals with the complexity of people, relationships and motivations that transform history into myth and turn myth into history. I do hope that you enjoy, as I said it is a bit long but I think well worth the read.

Peace,

Padre Steve+

“Danger is part of the friction of war. Without an accurate conception of danger we cannot understand war. That is why I have dealt with it here.” Carl Von Clausewitz [1]

When commanders send their troops into battle to execute the plans of their staff, they cannot forget that as Clausewitz noted that War is the province of danger and that:

“In the dreadful presence of suffering and danger, emotion can easily overwhelm intellectual conviction, and in the psychological fog it is so hard to form clear and complete insights that changes in view become more understandable and excusable….No degree of calm can provide enough protection: new impressions are too powerful, too vivid, and always assault the emotions as well as the intellect.” [2]

To re-engage our understanding of this issue is important, especially in the application of Mission Command where as General Martin Dempsey noted that “Understanding equips decision makers at all levels with the insight and foresight to make effective decisions, to manage the associated risks, and to consider second and subsequent order effects.” [3] The current and recent wars fought by the United States and its NATO and coalition allies have shielded many military professionals from this aspect of war, but it is still present and we should not ignore it. As noted in the 2006 edition of the Armed Forces Officer:

“The same technology that yields unparalleled success on the battlefield can also detach the warrior from the traditional ethos of the profession by insulating him or her from many of the human realities of war.” [4]

“The nature of the warrior leader is driven by the requirements of combat” [5]and courage, both “courage in the face of the danger, and the courage to accept responsibility” [6] are of paramount importance. In an era where the numbers of soldiers that actually experience combat or served in true combat conditions where the element of danger is ever present is shrinking, we can at least gain part of that understanding through the study of history, campaigns and battles and by actually walking the battlefields, and considering the effects of terrain, weather, exhaustion and the imagining danger faced in confronting an enemy on the field of battle. As such the Battle of Gettysburg and the climactic event of Pickett’s Charge on July 3rd is a good place to reimagine the element of danger from the point of view of the soldiers, but also the commanders involved in the action.

It is also a place that we can look to find the end of dreams, the shattering of legacies, the emergence of myth as history, and the terrible effects ill-conceived of plans gone awry.

Major General George Pickett and his division waited in Spangler’s Woods and in the swale behind Seminary Ridge and looked across the valley the separated them from the Federal positions on Cemetery Ridge. The troops for the most part were eager to fight and had not seen difficult action for about a year while their comrades in the Army of Northern Virginia had marched to glory. The division had been held in reserve and not seen action at Fredericksburg and they had missed the great victory at Chancellorsville entirely having been detached with Longstreet’s corps on the Suffolk excursion. Now these troops waited anxiously for their orders in the sultry summer heat which caused them to perspire and to drink from the canteens that they filled that morning.

The men varied in what they thought of the battle that they knew that was approaching. Some in Richard Garnett’s brigade were “in splendid spirits and confident of sweeping everything before them;…never was there anything like the same enthusiasm entering battle.” [7] Others were not so confident. In Armistead’s brigade Lieutenant James F. Crocker of the 9th Virginia who had been wounded at Malvern Hill surveyed the ridge before them and told a number of officers that the attack “was going to be another Malvern Hill, another costly day to Virginia and Virginians,” [8] while a Colonel in Pickett’s division noted that when the men were told of the attack that they went “being unusually merry and hilarious that they on a sudden had become as still and thoughtful as Quakers at a love feast.” [9] Their commander, George Pickett received the plan of attack from James Longstreet who later noted that Pickett “seemed to appreciate the severity of the contest he was about to enter…but was quite hopeful of success.” [10]

A member of Pickett’s staff noted years later that “It is said, that the condemned, in going to execution, the moments fly….To the good soldier, about to go into action, I am sure the moments linger. Let us not dare say, that with him, either individually, or collectively, is that ‘mythical love of fighting,’ poetical but fabulous; but rather, that it is the nervous anxiety to solve the great issue as speedily as possible, without stopping to count the cost.” [11]

Porter Alexander’s artillery began its bombardment at 1:07 p.m. As it did the Union artillery commenced a deliberate counter-fire, in which the Confederate infantry behind Seminary Ridge began to take a beating. Unlike the Confederate barrage which had mainly sailed over the Union troops on Cemetery Ridge causing few causalities, “a large proportion” of the Union “long shots landed squarely in the ranks of the gray soldiers drawn up to await the order to advance.” [12] Estimates vary but the waiting Confederates lost between 300-500 killed and wounded, the most affected was Kemper’s brigade of Pickett’s division which lost about 250 men, or 15% of its strength. [13] Other units lost significant numbers, with those inflicted on Pettigrew’s brigades further depleting their already sparse numbers.

The Union counter fire had an effect on many of the Confederates including Pickett. Alexander “found Pickett in a very positive and excited frame of mind.” [14] There are conflicting opinions of Pickett’s state of mind, supporters tending to believe the best about him and his conduct on the battlefield, while detractors, both his contemporaries and current historians allege that he was afraid and quite possibly minimizing his exposer to enemy fire due to his obsession with Sallie. Edwin Longacre wrote: “While not himself under fire, Pickett appears not to have taken the barrage too calmly. Aware that Longstreet had asked Alexander recommend “the most opportune time for our attack” based on the enemy’s response to his cannonade, Pickett at least twice sent couriers to as the colonel if they should go in.” [15]

Like in any historical account the truth probably lies in the middle of the extreme viewpoints and while we think that we know much about the greatest charge in the history of the United States, we are hindered by the lack of written accounts by most of the senior Confederate officers who took part in Pickett’s Charge. This complicates the task of attempting to separate the true from the false and the truth from a judgment or verdict rendered by a less than impartial judge. Lee, Hill and Longstreet “treated the charge as just one episode in long campaign reports, and modern readers, like some of the participants, can wonder how much of any of the three generals really saw once the firing started.” [16]

Since no reports of the Confederate division commanders are available, Pickett’s was suppressed because of how critical it was toward other commanders. Pettigrew and Pender were dead, Trimble was wounded and in a Federal prison and Harry Heth, Pickett’s cousin limited his report to the action of July 1st 1863. Likewise only two of the nine brigade commanders filed reports and none of them were from Pickett’s division, so it is hard to get a complete and accurate view from official sources. Longstreet discussed Pickett’s report and said that it “was not so strong against the attack as mine before the attack was made but his was made in writing and of official record.” [17] Pickett was reportedly furious at being force to destroy his report and refused to submit an edited report. So what we are left with on the Confederate side are the reports of two corps commanders and an army commander who were far away from the scene of the action, after action reports of regiments, many of which had lost their commander’s and most of their senior officers, and the recollections from men with axes to grind and or reputations to defend; some Longstreet, some Pickett, some Pettigrew.

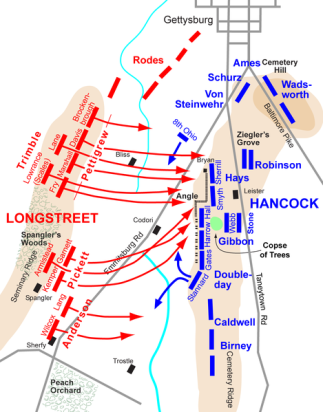

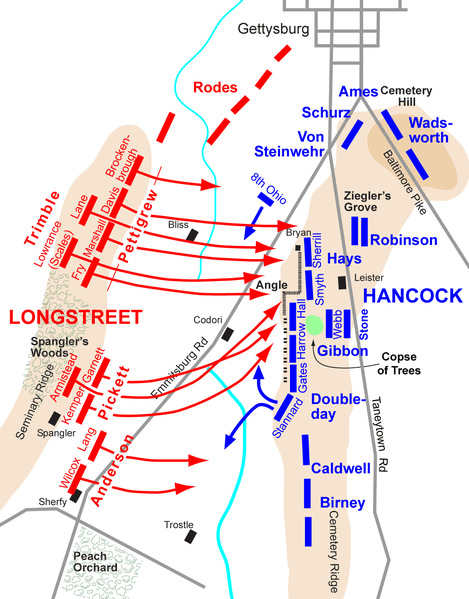

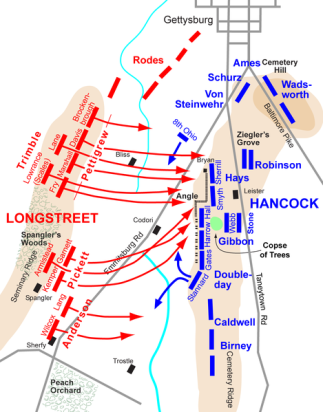

The assault force was composed of Pickett’s fresh division from First Corps, Harry Heth’s battered division now under Johnston Pettigrew which had already taken close to 40% casualties and two brigades of Pender’s division now commanded by Isaac Trimble. These two brigades, Lane’s which was fresh but Scales brigade, now under command of Colonel William Lowrence had suffered greatly on July 1st; its “casualty rate was 63% and it had lost its commander and no fewer than fifty-five field and company grade officers.” [18] And now, these battered the units began to take casualties from well directed Federal fire. George Stewart wrote: “In most armies, such a battered unit would have been sent to the rear for reorganization, but here it was being selected for a climactic attack!” [19]

“The Confederate losses mounted at an alarming rate. The psychological impact of artillery casualties was great, for the big guns not only killed but mangled bodies, tore them apart, or disintegrated them.” [20] A survivor wrote his wife days later: “If the crash of worlds and all things combustible had been coming in collision with each other, it could not have surpassed it seemingly. To me it was like the “Magazine of Vengeance” blown up.” [21] A soldier of Kemper’s brigade recalled that “The atmosphere was rent and broken by the rust and crash of projectiles…The sun, but a few minutes before so brilliant, was now darkened. Through this smoky darkness came the missiles of death…the scene beggars description…Many a fellow thought his time had come…Great big, stout hearted men prayed, loudly too….” [22] Colonel Joseph Mayo of the 3rd Virginia regiment was heavily hit, one of its survivors wrote “when the line rose up to charge…it appeared that as many were left dead and wounded as got up.” [23]

On the opposite ridge Union forces were experiencing the same kind of intense artillery fire. But these effects were minimized due to the prevalent overshooting of the Confederate artillery as well as the poor quality of ammunition. This resulted in few infantry casualties with the worst damage being taken by a few batteries of artillery at the angle. Soldiers behind the lines took the worst beating, but “the routing of these non-combatants was of no military significance,” [24] This did create some problems for the Federals as Meade was forced to abandon their headquarters and the Artillery Reserve was forced to relocate “a little over a half mile to the rear.” [25] The effects of this on operations were minimal as Brigadier General Robert Tyler commanding the Artillery Reserve “posted couriers at the abandoned position, should Hunt want to get in touch with him.” [26]

Despite the fusillade Meade maintained his humor and as some members of his staff tried to find cover on the far side of the little farmhouse quipped:

“Gentlemen, are you trying to find a safe place?…You remind me of the man who drove the oxen team which took ammunition for the heavy guns to the field at Palo Alto. Finding himself in range, he tipped up his cart and hid behind it. Just then General Taylor came along and shouted “You damned fool, don’t you know you are no safer there than anywhere else?” The driver responded, “I don’t suppose I am general, but it kind of feels so.” [27]

A bombardment of this magnitude had never been seen on the American continent, but despite its apparent awesome power, the Confederate artillery barrage had little actual effect on the charge. The Prussian observer traveling with Lee’s headquarters “dismissed the barrage as a “Pulververschwindung,”…a waste of powder. [28] The Federal infantry remained in place behind the stone wall on Cemetery Ridge ready to meet the assault. Henry Hunt replaced his damaged artillery batteries on Cemetery Ridge. But even more importantly Lieutenant Colonel Freeman McGilvery’s massive battery was lying undetected where it could deliver devastating enfilade fire as the Confederate infantry neared their objective. Likewise, Rittenhouse’s batteries on Little Round Top and Osborne’s on Cemetery Hill were unaffected by the Confederate bombardment were poised to wreak destruction on the men of the three Confederate divisions.

Unlike the Federal Army which had its large pool of artillery battalions in the Artillery Reserve with which to replace batteries that had taken casualties or were running low on ammunition, Porter Alexander had no fresh batteries or ammunition: “soon the drivers of the caissons found that the heavy fire had exhausted their supply of shot and shell, and the had to go even farther to get it from the reserve train. As a result some of the guns remained mute and their gunners stood helpless during the cannonade and charge, for Alexander had no batteries in reserve to replace them.” [29]

There were two reasons for this. First was that Lee had reorganized the artillery before Chancellorsville. He eliminated the artillery reserve and assigned all artillery battalions and batteries directly to the three infantry corps. This meant that Alexander could only draw upon the battalions assigned to First Corps and had no operational control over the batteries of Ewell’s Second Corps or Hill’s Third Corps.

The second was due to the meddling of Brigadier General William Pendleton, Lee’s senior artilleryman who as a staff officer had no command authority over any of the guns in the army. Pendleton relocated the artillery trains of First Corps further to the rear without informing Alexander or Longstreet. Likewise, Pendleton also ordered the eight guns of the Richardson’s artillery away without notifying anyone. These were guns that Alexander was counting on to provide direct support to the attack by advancing them to provide close support to the infantry.

At about 2:20 p.m. Alexander, knowing that he was running short of ammunition sent a note to Picket and Pettigrew advising them:

“General: If you are to advance at all, you must come at once or we will not be able to support you as we ought. But the enemy’s fire has not slackened and there are still 18 guns firing from the cemetery.” [30]

About twenty minutes later Alexander saw some of the Federal guns along Cemetery Ridge begin to limber up and depart. He also noticed a considerable drop off in Federal fire. He interpreted this to mean that his guns had broken the Federal resistance, and at 2:40 Alexander sent word to Pickett “For God’s sake come quick or my ammunition will not let me support you.” [31]

However, what Alexander did not realize was that what was happening on Cemetery Ridge had little to do with his bombardment but instead was directed by Henry Hunt. Hunt ordered batteries low on ammunition or that had sustained damage to withdraw and was replacing them with fresh batteries that Alexander could not see, although he assumed that such might be the case, he noted that the withdraw of batteries was new, for “the Federals had never done anything of that sort before, & I did not believe that they were doing it now.” [32] He had also decided to conserve ammunition by ordering an “immediate cessation and preparation for the assault to follow.” [33]

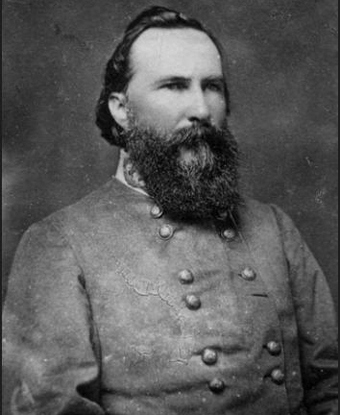

Alexander’s message reached Pickett and Pickett immediately rode off to confer with Longstreet. Pickett gave the message to Longstreet who read it “and said nothing. Pickett said, “General, shall I advance!” Longstreet, knowing it had to be, but unwilling to give the word, turned his face away. Pickett saluted and said “I am going to move forward, sir” galloped off to his division and immediately put it in motion.” [34] Sadly Pickett “had no inkling that his corps commander was immovably opposed to the charge” [35] and Pickett, caught up in the moment with the excitement of leading his Division into battle did not notice his friend’s mood.

A few minutes later Longstreet rode to find Alexander. Meeting him at 2:45 and Alexander informed him of the shortage of ammunition. The news was surprising to Longstreet as neither “he nor Lee had checked on the supply of ammunition during the morning.” [36] the news took him aback enough that he “seemed momentarily stunned” [37] by it. Longstreet told Alexander: “Stop Pickett immediately and replenish your ammunition.” [38] But Alexander now had to give Longstreet even worse news telling him “I explained that it would take too long, and the enemy would recover from the effect of our fire was then having, and too that we had, moreover, very little to replenish it with.” [39] Longstreet continued to ride with Alexander and again eyed the Federal positions on Cemetery Ridge with his binoculars. As he looked at the Federal position he slowly spoke and said “I don’t want to make this attack,” pausing between sentences as if thinking aloud. “I believe it will fail- I do not know how it can succeed- I would not make it even now, but Gen. Lee has ordered it and expects it.” [40] Alexander, who as a battalion commander now in charge of First Corps artillery was very uncomfortable, he later wrote:

“I had the feeling that he was on the verge of stopping the charge, & that with even slight encouragement he would do it. But that very feeling kept me from saying a word, or either assent I would not willingly take any responsibility in so grave a matter & I had almost a morbid fear of causing any loss of time. So I stood by, & looked on, in silence almost embarrassing.” [41]

While Longstreet was still speaking Pickett’s division swept out of the woods to begin the assault, Alexander knew that “the battle was lost if we stopped. Ammunition was too low to try anything else, for we had been fighting for three days. There was a chance, and it was not my part to interfere.” [42]

Despite this Pickett and many of his soldiers were confident of success, and: “no officer reflected the men’s confidence better than George Pickett. There was no fatalism in him. Believing that his hour of destiny had come and expecting to take fortune at its flood, he rode down the slope like a knight in a tournament.” [43] Pickett was “an unforgettable man at first sight” [44] Pickett wore a “dark mustache drooping and curled at the ends, a thin goatee, and hair worn long and curled in ringlets. His hair was brown, and in the morning sunlight it reflected auburn hints. George Pickett stood slender and graceful at the middle height, and carried himself with an air. Dandified in dress, he was the most romantic looking of all Confederates, the physical image of that gallantry implicit in the South’s self concept. [45]

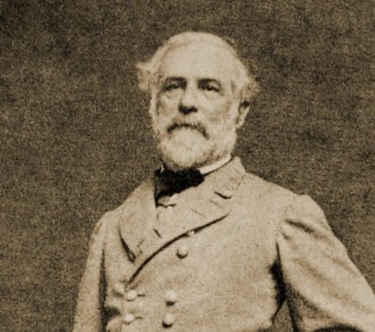

George Pickett was “born to wealth and privilege in a Neo-feudal society” [46] and came from an old and distinguished Virginia family with a long military heritage dating to the Revolution and the War of 1812. He attended the Richmond Academy until he was sixteen and had to withdraw due to the financial losses his parents had suffered during the panic of 1837.

Major General George Pickett C.S.A.

This led to the young Pickett being sent to live with and study law under his mother’s older brother, the future President, Andrew Johnston in Quincy Illinois. The family’s continued financial distress led them to get George to consider the free education provided by West Point. His mother asked Johnston to assist and Johnston set about obtaining an appointment for his nephew. “As befit an up-and-coming politician, his quest was short and successful. His Springfield acquaintances included a United States Congressman who happened to be a fellow Southerner and brother Whig, Kentucky native John T. Stuart.” [47] There is a long running myth that connects Pickett’s appointment to West Point to Abraham Lincoln, but it is fiction, fabricated by Pickett’s widow Sallie long after her husband and Lincoln’s death. [48]

Pickett entered West Point in 1842 where he was described by a fellow cadet thought “a jolly good fellow with fine natural gifts sadly neglected” [49] through his tendency to “demonstrate in word and deed that henhouse neither to authority nor submit to what’re considered the Academy’s narrow, arbitrary, unrealistic, harshly punitive, and inconsistently applied code of conduct” [50] became a loyal patron of Benny Havens tavern where he “was stealing away regularly now to life his glass in good fellowship…” [51]

Pickett’s academic performance, as well as his record of disciplinary infractions at West Point was exceptionally undistinguished. He racked up vast amounts of demerits for everything from being late to class, chapel and drill, uniform violations and pranks on the drill field where he mocked those who observed proper drill and ceremonies. Pickett graduated last in the class of 1846, something that his vast amount of demerits contributed.

His widow Sallie wrote after his death that he accumulated them “so long as he could afford the black marks and punishments they entailed. He curbed his harmful behavior, however, when he found himself approaching the magic number of 200 demerits per year that constituted grounds for dismissal.” [52] Pickett finally graduated “only five behavioral demerits short of expulsion.” [53] The graduating class included George McClellan, A.P. Hill, Thomas, later “Stonewall” Jackson as well as a number of other cadets, most of whom who went on to distinguished military and other careers. At West Point Pickett was considered to be the class clown by many of his classmates was “the most popular and prominent young man in the class.” [54] Among the many friends that he made was an upperclassman named Ulysses S. Grant and “their friendship would span decades and would survive the fire of a war that placed them at sword’s point.” [55]

Lieutenant Pickett at Chapultepec

Pickett was commissioned into the infantry and served alongside James Longstreet in the Mexican War where “fought valiantly in a number of battles, including Contreras, Churubusco, El Molino Del Rey” [56] during the Mexican War. Pickett distinguished himself at Chapultepec where “he had been the first American to scale the ramparts of Chapultepec, where he planted the flag before the admiring gaze of his friend Longstreet.” [57] During that assault Longstreet was wounded and “Pickett had snatched the colors and planted them on the castle heights for all to see and cheer.” [58] For his actions he received a brevet promotion to First Lieutenant.

Following the war Pickett married but was widowed less than two years later when his wife Sally Minge Pickett died during childbirth along with their infant son in 1852 The loss was devastating to the young officer, he went into a deep depression caused by grief and considered leaving the army. He was persuaded by friends, peers and understanding commanding officers to remain.

While on leave following Sally’s death he was at Fort Monroe, laying under an umbrella at Point Comfort when a child approached him and took pity on him. The child was the nine year old La Salle “Sallie” Corbell and she broke through his emotional defenses by persistently, as only a child can do asking what the source of his grief was. Pickett told the child that “his heart had been broken by a sorrow almost too great to bear.” When the child asked how one’s heart could break, “he replied that ‘God broke it when he took from him his loved ones and left him so lonely.” [59] While Pickett may not had thought much of the meeting, he did give the little girl a ring and a golden hear bearing his wife’s name. He likely expected never to see her again but though she was a child she “was a willful and determined one. She knew her own mind and heart, both told her that one day she would marry George Pickett.” [60]

Pickett returned to Texas to serve with the 8th Infantry and was promoted to Captain and ordered to take command of the newly raised Company “D” 9th Infantry at Fort Monroe. Transferred to the Pacific Northwest he married Widowed after that war he served in the Pacific Northwest where he took a Native American wife who bore him a son, however she did not survive childbirth and when she died in early 1858 Pickett was again widowed. In 1859 Captain Pickett faced down British troops from the Hudson Bay Company in an incident now known at the “Pig War” which at its heart was a dispute about whether the British or the Americans own San Juan Island. The dispute, which brought the two nations to the brink of war, was settled without bloodshed, save for the unfortunate pig, and Pickett became a minor celebrity in the United States and anathema to the British.

When Virginia seceded from the Union, Pickett like many other southern officers was conflicted in his feelings and loyalties and “hoped to the last that he would have to take up arms against neither state nor country.” [61] Pickett resigned his commission on June 25th 1861. He wrote to Sallie with who he now maintained a frequent correspondence about his decision and decidedly mixed feelings as he:

“Always strenuously opposed disunion…” But “While I love my neighbor, i.e., my country, I love my household, i.e., my state, more, and I could not be an infidel and lift my sword against my own kith and kin, even though I do believe…that the measure of American greatness can be achieved only under one flag.” [62]

Pickett returned to Virginia by a circuitous route where he was commissioned as a Captain in the new Confederate army on September 14th and two weeks later was promoted to Colonel and assigned to command forces along the Rappahannock. Though he had as yet seen no combat serving in the Confederate army Pickett was promoted to a brigadier General and assigned to command a Virginia brigade belonging to Longstreet’s division.

Pickett led his brigade well on the peninsula and at Williamsburg was instrumental in routing an advancing Federal force, and at Seven Pines had helped repel a dire threat to the Confederate position. At Gaines Mill Pickett was wounded in the shoulder during the assault put out of action and placed on convalescent leave to recover from his wounds. During his convalescence he fell in love with an old acquaintance; “La Salle Corbell,” who as a young girl had cheered him after the loss of his wife “now a beautiful young woman nursed him back to health and started a chain reaction that would nearly engulf the Confederate officer.” [63]

Pickett was promoted to Major General in October 1862 and was assigned command of the division formerly commanded by David R. Jones, which was assigned to Longstreet’s First Corps. The division was sent to peripheral areas and took no part in the battles of late 1862 or Chancellorsville serving instead in the Tidewater with Longstreet’s corps. The corps took part in a series of operations against Union forces in the Hampton Roads area and Pickett’s division bested a Federal force at Suffolk on April 24th 1863, though it was hardly a true test of his ability to command the division in combat. During this time Pickett spent much time visiting La Salle, much to the concern of some of his officers and Longstreet’s staff, and by the time the corps left the area the two were engaged to be married.

When the Division returned to the Army of Northern Virginia after Chancellorsville it was among the forces considered by Jefferson Davis to be sent west for the relief of Vicksburg. Since that operation never materialized the division was assigned to accompany First Corps with the army during the upcoming Pennsylvania campaign. However, much to the consternation of Lee, Longstreet and Pickett two of its brigades were detached by the order of Jefferson Davis to protect Richmond from any Federal incursion.

During the advance into Pennsylvania the division, now composed of the brigades of James Kemper, Lewis Armistead and Richard Garnett was the trail division in Longstreet’s corps and often, in the absence of cavalry assigned to guard the corps and army trains. Due to its late release from these duties at Chambersburg, Pickett’s Division did not arrive at Gettysburg until late afternoon on July 2nd. Lee decided that they would not be needed that day and Longstreet placed that the division in bivouac at Marsh Creek for the night, sending word by messenger to “tell Pickett I will have work for him tomorrow.” [64]

Pickett spent the night with his soldiers and woke them about 3 a.m. After a quick breakfast Pickett moved the division to Seminary Ridge marshaling his troops in Spangler’s Woods where there was a modicum of protection from Federal fires and observation. However, despite these advantages it placed his division about 1000 yards from the extreme right of Pettigrew’s division with which he would have to coordinate his attack that fateful day.

Pickett scribbled a final note to Sallie as his troops prepared to attack. “Oh, may God in his mercy help me as He never has helped me before…remember always that I love you with all my heart and soul… That now and forever I am yours.” [65]

When Pickett’s division as well as those of Pettigrew and Trimble swept out of the wood to begin the attack the last chance to stop the attack ended. As Pickett’s brigades moved out, Pickett galloped up, as debonair as if he had been riding through the streets of the Richmond under the eye of his affianced” [66] and “every soldier within hearing was stirred by Pickett’s appeal” [67] as he shouted “Remember Old Virginia!” or to Garnett’s men “Up, men, and to your posts! Don’t forget today that you are from Old Virginia!” [68] But when Garnett asked if there were any final instructions Pickett was told “I advise you to make the best kind of time in crossing the valley; it’s a hell of an ugly looking place over yonder.” [69]

Armistead called out to his soldiers, “Men, remember who you are fighting for! Your homes, your firesides, and your sweethearts! Follow Me!” [70]Armistead’s example had a major impact on his brigade, men were inspired, as one later wrote “They saw his determination, and they were resolved to follow their heroic leader until the enemy’s bullets stopped them.” [71] about 500 yards to Pickett’s left Pettigrew exhorted his men “for the honor of the good old North State, forward.” [72]

Pickett’s division “showed the full length of its long gray ranks and shining bayonets, as grand as a sight as ever a man looked on.” [73] The sight was impressive on both sides of the line, a Confederate Captain recalling the “glittering forest of bayonets” the two half mile wide formations bearing down “in superb alignment.” [74] The sight of the amassed Confederates moving forward even impressed the Federals. Colonel Philippe Regis de Trobriand, a veteran of many battles in Europe and the United States recalled “it was a splendid sight,” [75] and another recalled that the Confederate line ‘gave their line an appearance of being irresistible.” [76]

But the Federals were confident. Having withstood the Confederates for two days and having survived the artillery bombardment the Union men eagerly awaited the advancing Confederates. Directly facing the Confederate advance in the center of the Union line was the division of Pickett’s West Point Classmate and North Carolina native who remained with the Union, John Gibbon. The cry went out “Here they come! Here they come! Here comes the infantry!” [77] To the left of Gibbon Alexander Hays called to his men “Now boys look out…now you will see some fun!” [78]

The Confederates faced difficulties as they advanced, and not just from the Union artillery which now was already taking a terrible toll on the advancing Confederates. Stuck by the massed enfilade fire coming from Cemetery Hill and Little Round Top continued their steady grim advance. Carl Schurz from his vantage point on Cemetery Hill recalled:

“Through our field-glasses we could distinctly see the gaps torn in their ranks, the grass dotted with dark spots- their dead and wounded….But the brave rebels promptly filled the gaps from behind or by closing up on their colors, and unasked and unhesitatingly they continued with their onward march.” [79]

Pettigrew’s division was met by fire which enveloped them obliquely from Osborne’s thirty-nine guns emplaced on Cemetery Hill. On their left flank a small Federal regiment, the 8th Ohio lay in wait unnoticed by the advancing Confederates. Seeing an opportunity the regiment’s commander Lieutenant Colonel Franklin Sawyer deployed his 160 men in a single line, took aim at Brockenbrough’s Virginia brigade some two hundred yards ahead of the Emmitsburg Road, and opened a devastating fire. “Above the boiling clouds the Union men could see a ghastly debris of guns, knapsacks, blanket rolls, severed human heads, and arms and legs and parts of bodies tossed into the air by the impact of the shot.” [80] So sudden and unexpected was this that the Confederates panicked and “fled in confusion…” to the rear where they created more chaos in Trimble’s advancing lines as one observed they “Came tearing through our ranks, which caused many men to break.” [81] The effect on Confederate morale was very important, for “the Army of Northern Virginia was not used to seeing a brigade, even a small one, go streaming off to the rear, with all its flags….Even Pickett’s men sensed that something disastrous had happened on the left….” [82]

In one fell swoop Pettigrew was minus four regiments. Brockenbrough was singularly ineffective in leading his men, he “was a nonentity who did not know how to control his recalcitrant rank and file; nor did he have the presence to impress his subordinate officers and encourage them to do his bidding.” [83] The disaster that had overtaken Brockenbrough’s brigade now threatened another important component of Lee’s plan- protecting the left flank of the assaulting force. As Brockenbrough’s brigade collapse the vital protection of the left flank collapsed with it.

Pettigrew’s division continued its advance after Brockenbrough’s brigade collapsed, but the Confederate left was already beginning to crumble. “Sawyer changed front, putting his men behind a fence, and the regiment began firing into the Confederate flank.” [84]with Davis’s brigade now taking the brunt of the storm of artillery shells from Osborne’s guns. This brigade had suffered terribly at the railroad cut on July 1st, especially in terms of field and company grade officers was virtually leaderless, and “the inexperienced Joe Davis was helpless to control them.” [85] To escape the devastating fire Davis ordered his brigade to advance at the double quick which brought them across the Emmitsburg Road ahead of the rest of the division, where they were confronted by enfilade canister fire from Woodruff’s battery to its left, as well as several regiments of Federal infantry and from the 12th New Jersey directly in their front. A New Jersey soldier recalled “We opened on them and they fell like grain before the reaper, which nearly annihilated them.” [86] Davis noted that the enemy’s fire “commanded our front and left with fatal effect.” [87] Davis saw that further continuing was hopeless and ordered his decimated brigade “to retire to the position originally held.” [88]

Pettigrew’s remain two brigades continued grimly on to the Emmitsburg Road, now completely devoid of support on their left flank. Under converging fire from Hay’s Federal troops the remaining troops of Pettigrew’s command were slaughtered. Hay’s recalled “As soon as the enemy got within range we poured into them and the cannon opened with grape and canister [, and] we mowed them down in heaps.” [89] The combination of shot, shell, canister and massed musket fire “simply erased the North Carolinian’s ranks.” [90]Pettigrew was wounded, Colonel Charles Marshall was killed fifty yards from the stone wall and “only remnants of companies and regiments remained unscathed.” Soon the assault of Pettigrew’s division was broken:

“Suddenly Pettigrew’s men passed the limit of human endurance and the lines broke apart and the hillside covered with men running for cover, and the Federal gunners burned the ground with shell and canister. On the field, among the dead and wounded, prostrate men could be seen holding up handkerchiefs in sign of surrender.” [91]

Trimble’s two brigades fared no better. Scales brigade, now under the command of Colonel W. Lee Lowrence “never crossed the Emmitsburg Road but instead took position along it to fire at the enemy on the hill. The soldiers from North Carolina who two days before had marched without flinching into the maw of Wainwright’s cannon on Seminary Ridge could not repeat the performance.” [92] Trimble was severely wounded in the leg and sent a message to Lane to take command of the division. The order written in the third person added a compliment to his troops: “He also directs me to say that if the troops he had the honor to command today for the first time couldn’t take that position, all hell can’t take it.” [93] Lane attempted to rally the troops for one last charge when one of his regimental commanders exploded telling him “My God, General, do you intend rushing your men into such a place unsupported, when the troops on the right are falling back?” [94] Lane looked at the broken remains of Pettigrew’s division retiring from the field and ordered a retreat. Seeing the broken remnants of the command retreating, an aide asked Trimble if the troops should be rallied. Trimble nearly faint from loss of blood replied: “No Charley the best these brave fellows can do is to get out of this,” so “let them get out of this, it’s all over.” [95] The great charge was now over on the Confederate left.

The concentrated Federal fire was just as effective and deadly on the Confederate right. Kemper’s brigade, on the right of Pickett’s advance was mauled by the artillery of Rittenhouse on Little Round Top, which “tracked their victims with cruel precision of marksmen in a monstrous shooting gallery” and the overs “landed their shots on Garnett’s ranks “with fearful effect.” [96]

As the Confederates advanced Pickett was forced to attempt to shift his division to the left to cover the gap between his and Pettigrew’s division. The move involved a forty-five degree oblique and the fences, which had been discounted by Lee as an obstacle which along the Emmitsburg Road “virtually stopped all forward movement as men climbed over them or crowed through the few openings.” [97] Pickett’s division’s oblique movements to join with Pettigrew’s had presented the flank of his division to McGilvery’s massed battery. The movement itself had been masterful, the execution of it under heavy fire impressive; however it meant the slaughter of his men who were without support on their right flank.

Pickett himself was doing his best to direct the movements of his Division. Placing himself just behind his Division he “kept his staff busy carrying messages to various generals and performing other duties on the field. At different times he sent his aides back to Confederate lines to inform Longstreet of his need for reinforcements, or to direct Wilcox when to advance his troops, or to ask Major James Dearing for artillery support.” [98] While some of Pickett’s detractors attempt to accuse him of cowardice, including inventing fables about him drinking behind the lines, the facts do not substantiate the accusations. Likewise, Pickett’s position about one hundred yards behind his advancing troops was optimal for command and control purposes.

Though he did not have operational control of Pettigrew’s division, “when he saw it beginning to falter, he ordered Captains E.R. Baird and W. Stuart Symington to help rally them. Then Pickett himself galloped to the left in an effort to steady the men.” [99]

As Pickett’s division advanced into the Plum Run Valley they were met by the artillery of Freeman McGilvery, who wrote that the “execution of the fire must have been terrible, as it was over a level plain, and the effect was plain to be seen. In a few minutes, instead of a well-ordered line of battle, there were broken and confused masses, and fugitives fleeing in every direction.” [100]

Kemper’s brigade which had the furthest to go and the most complicated maneuvering to do under the massed artillery fire suffered more damage. The swale created by Plum Run was a “natural bowling alley for the projectiles fired by Rittenhouse and McGilvery” [101] was now flanked by Federal infantry as it passed the Condori farm. The Federal troops were those of the Vermont brigade commanded by Brigadier General George Stannard. These troops were nine month volunteers recruited in the fall of 1862 and due to muster our in a few days. They were new to combat, but one of the largest brigades in the army and 13th Vermont “had performed with veteran like precision the day before” [102] leading Hancock to use them to assault the Confederate right. The Vermonters were positioned to pour fire into the Confederate flank, adding to the carnage created by the artillery, and the 13th and 16th Vermont “pivoted ninety degrees to the right and fired a succession of volleys at pistol range on the right of Pickett’s flank.” [103]

Kemper had not expected this, assuming that the Brigades of Wilcox and Perry would be providing support on the flank. As he asked a wounded officer of Garnett’s brigade if his wound was serious, the officer replied that he soon expected to be a prisoner and asked Kemper “Don’t you see those flanking columns the enemy are throwing on our right to sweep the field?” [104] Kemper was stunned but ordered his troops to rush federal guns, but “they were torn to pieces first by the artillery and then by the successive musketry of three and a half brigades of Yankee infantry.” [105] Kemper was fearfully wounded in the groin and no longer capable of command. His brigade was decimated and parts of two regiments had to refuse their line to protect the flank, and those that continued to advance had hardly any strength left with which to succeed, the Confederate left was no for all intents and purposes out of the fight.

Now that fight was left in the hands of Armistead and Garnett’s brigades, and at this moment in the battle, the survivors of those units approached the stone wall and the angle where they outnumbered the Federal defenders, one regiment of which, the 71st Pennsylvania had bolted to the rear.

This left the decimated remains of Lieutenant Alonzo Cushing’s battery of artillery alone to face the advancing Confederates. Cushing who had already received multiple wounds in his should and groin and was desperately wounded. A number of his guns had been disabled and his battery had taken significant numbers of casualties during the Confederate bombardment. Cushing was another of the young West Point graduates who directed batteries at key points during the battle who was not only a skilled artilleryman, but a gifted leader and a warrior who won the respect of his men. One corporal said that Cushing “was the best fighting man I ever saw” while another recollected “He was so cool and calm as I ever saw him, talking to the boys between shots with the glass constantly to his eyes, watching the effect of our shots.” [106]

He received permission from the commander of the Philadelphia Brigade, Alexander Webb, among whose regiments his battery was sited to advance his guns to the wall. Though he was already desperately wounded in the shoulder and the groin, Cushing remained with his gunners. When a subordinate suggested that he go to the rear he replied “I will stay right here and fight it out or die in the attempt.” [107]

When Webb came to his battery and told Cushing that he believed that the Confederate infantry was about to assault their position Cushing replied “I had better run my guns right up to the stone fence and bring all my canister alongside each piece.” [108] From the stone fence the young officer directed the fire of his remaining guns. His gunners “rammed in more loads of double canister when the Confederates were less than seventy yards away.” [109] When the Garnett and Armistead’s survivors were just a hundred yards away from the wall, “Cushing ordered triple canister. He was hit a third time, this time in his mouth killing him instantly.” [110] The surviving gunners, now commanded by a sergeant fought hand to hand against the Confederates as they were overrun.

The survivors of Garnett’s brigade, led by their courageous but injured commander, who rode fully exposed to Federal fire on his horse, crossed the Emmitsburg Road and pushed forward overwhelming the few Federals remaining at the wall. They reached the outer area of the angle “which had been abandoned by the 71st Pennsylvania” and some of his men “stood on the stones yelling triumphantly at their foes.” [111] Armistead, sword raised with his hat still on it, climbed over the wall shouting to his men “Come on boys! Give them the cold steel”…and holding his saber high, still with the black hat balanced on its tip for a guidon, he stepped over the wall yelling as he did so: “Follow me!” [112]

Armistead and his remaining soldiers, about one hundred in total, waded into the wreckage of Cushing’s battery and some began to attempt to turn the guns on the Federals. “For a few moments there was a sense of supreme exultation as the rebels swarmed over the fence, forced back two Federal companies, and swallowed up a third. Armistead was the first to reach Cushing’s two guns, placing a hand on one of them and yelling, “The day is ours men, come turn this artillery upon them.” [113]

However, the triumph of Armistead and his band was short lived; the 72nd Pennsylvania was rushed into the gap by the brigade commander Brigadier General Alexander Webb. The climax of the battle was now at hand and “the next few minutes would tell the story, and what that story would be would all depend on whether these blue-coated soldiers really meant it…. Right here there were more Confederates than Federals, and every man was firing in a wild, feverish haste, with smoke settling down thicker and thicker.” [114] The 69th Pennsylvania, an Irish regiment under Colonel Dennis O’Kane stood fast and their fire slaughtered many Confederates. Other Federal regiments poured into the fight, famous veteran regiments the 19th and 20th Massachusetts, the 7th Michigan and the remnants of the 1st Minnesota who had helped stop the final Confederate assault on July 2nd at such fearful cost.

Dick Garnett, still leading his troops “muffled in his dark overcoat, cheered his troops, waving a black hat with a silver cord” [115] when he was shot down, his frightened horse running alone off the battlefield, a symbol of the disaster which had befallen Pickett’s division. Armistead reached Cushing’s guns where he was hit by several bullets and collapsed mortally wounded. “Armistead had been the driving force behind the last effort, there was no one else on hand to take the initiative. Almost as quickly as it had come crashing in, the Rebel tide inside the outer angle ebbed back to the wall.” [116]

For a time the Confederate survivors engaged Webb’s men in a battle at the wall itself in a stubborn contest. A Federal regimental commander wrote “The opposing lines were standing as if rooted, dealing death into each other.” [117] The Federals launched a local counterattack and many Confederates elected to surrender rather than face the prospect of retiring across the battlefield that was still swept by Federal fire.

Webb had performed brilliantly in repulsing the final Confederate charge and “gained for himself an undying reputation. Faced with defeat, he accepted the challenge and held his men together through great personal exertion and a willingness to risk his life.” [118] For his efforts he was belatedly awarded the Medal of Honor.

Webb, like John Buford on July 1st, Strong Vincent, Freeman McGilvery and George Sears Greene on July 2nd, was instrumental in the Union victory. Hancock said of Webb “In every battle and on every important field there is one spot to which every army [officer] would wish to be assigned- the spot upon which centers the fortunes of the field. There was but one such spot at Gettysburg and it fell to the lot of Gen’l Webb to have it and to hold it and for holding it he must receive the credit due him.” [119]

The survivors of Pickett, Pettigrew and Trimble’s shattered divisions began to retreat, Lee did not yet understand that his great assault had been defeated, but Longstreet, who was in a position to observe the horror was. He was approached by Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle, a British observer from the Coldstream Guards. Fremantle did not realize that the attack had been repulsed, having just seen one of Longstreet’s regiments “advancing through the woods in good order” and unwisely bubbled “I would not have missed this for anything.” [120] Longstreet replied with a sarcastic laugh “The devil you wouldn’t” barked Longstreet. “I would have liked to have missed this very much; we’ve attacked and been repulsed. Look there.” [121]

Fremantle looked out and “for the first time I then had a view of the open space between the two positions, and saw it covered with Confederates slowly and sulkily returning towards us in small broken parties, under a heavy fire of artillery.” [122] Henry Owen of the 18th Virginia wrote that the retreating men “without distinction of rank, officers and privates side by side, pushed, poured and rushed in a continuous stream, throwing away guns, blankets, and haversacks as they hurried on in confusion to the rear.” [123]

It was a vision of utter defeat. The Pickett, who had seen his division destroyed and had been unable to get it additional support was distraught. An aide noted that Pickett was “greatly affected and to some extent unnerved” [124] by the defeat. “He found Longstreet and poured out his heart in “terrible agony”: “General, I am ruined; my division is gone- it is destroyed.” [125] Lee had come up by now and attempted to comfort Pickett grasping his hand and telling him: “General, your men have done all that they could do, the fault is entirely my own” and instructed him that he “should place his division in the rear of this hill, and be ready to repel the advance of the enemy should they follow up their advantage.” [126] The anguished Pickett replied, “General Lee, I have no division now. Armistead is down, Garnett is down and Kemper is mortally wounded.” [127] Lee “missed the point of Pickett’s anguish completely” and attempted to console Pickett again and told the distraught General, “General Pickett…you and your men have covered themselves in glory.” [128]

Pickett, the romantic true believer in the cause refused to be consoled and told Lee “not all the glory in the world, General Lee, can atone for the widows and orphans this day has made.” [129] While Longstreet and Lee maintained their composure, Pickett “felt an overpowering sense of helplessness as he observed the high tide from Emmitsburg Road and the subsequent retreat of his shattered division. It was too much for the mercurial romantic to absorb.” [130] But Pickett was not alone, Cadmus Wilcox told Lee as he returned from the assault that he “came into Pennsylvania with one of the finest brigades in the Army of Northern Virginia and now all my people are gone.” [131]

When others attempted to stop the flight of his men Pickett countermanded them and ordered his survivors to return to the site where they had bivouacked the previous night. A soldier from the 18th Virginia who saw the retreat noted that at Willoughby Run:

“The fugitives, without distinction of rank, officers and privates side by side pushed, poured and rushed in a continuous stream, throwing away guns, blankets, and haversacks as they hurried in confusion toward the rear.” Before long there was another attempt to restore order, but again Pickett intervened. “Don’t stop any of my men!” he cried. “Tell them to come to the camp we occupied last night.” As he said this he was “weeping bitterly,” and then he rode on alone toward the rear.” [132]

When the survivors finally assembled the next morning they numbered less than 1000 out of the approximately 5000 troops who Pickett led into the attack remained. “Four out of every five of Pickett’s men had been either killed, wounded, or captured. Two of his three brigadiers were gone, probably dead, the third perhaps mortally wounded. Every one of his regimental commanders had been killed, wounded or captured.” [133]

During the retreat Pickett and his remaining soldiers would be assigned to the task of being the Provost Guard for the army, escorting Federal prisoners back during the long retreat back to Virginia. For them, it was a humiliating experience.

Pickett was never the same after the charge of July 3rd 1863. Pickett’s after action report which complained about the lack of support his division received was suppressed and destroyed by Lee who wrote Pickett “You and your men have crowned yourselves in glory… “But we have an enemy to fight, and must carefully, at this critical moment, guard against dissections which the reflections in your report will create.” [134]

George and La Salle “Sallie” Pickett circa 1865

Pickett married La Salle “Sallie” Corbell in September of 1863, and the marriage would last until his death in 1875. Sallie, impoverished by the death of “her soldier” took up writing as well as speaking tours in both the South and the North. Sallie was a stalwart defender of her husband, who she said “had the keenest sense of justice, most sensitive consciousness of right, and the highest moral courage” but also “opposing “hatred, sectionalism and strife.” [135] Though much of her work was panned by historians and shunned by established magazines and periodicals; her writing were published by newer popular magazines. Her book The Heart of a Soldier, as Revealed in the Intimate Letters of General George Pickett, C.S.A. was for the most part fabrications authored by her, but she found a niche in newer popular magazines and journals, including Cosmopolitan for which she authored a ten part serial of the Pickett family story on the fiftieth anniversary of the battle. Sallie Pickett’s:

“idealized portrait of her husband made him a Confederate hero. He never reached the status of Robert E. Lee or “Stonewall” Jackson, but his association with the famed but futile charge at Gettysburg helped. Virginia veterans and newspapers began romanticizing Pickett’s all-Virginia division’s role soon after the battle; it was almost by association that George too would share in this idolization…” [136]

Pickett retained command of his division which was reconstituted after Gettysburg and shipped off to North Carolina where he and it performed adequately but without marked distinction. It performed well in the defensive battles around Richmond and Petersburg. The end came at the battle at Five Forks where Pickett’s grossly under strength division was deployed on the far right of the Confederate line was overwhelmed by a massive assault by Sheridan’s cavalry and the Fifth Corps which destroyed it as a fighting formation. Pickett, who had successfully repulsed an attack by Sheridan the previous day did not expect an attack and was away from his division at a Shad bake with Rooney Lee when the attack came. “No cowardice was involved; Pickett simply misjudged the situation by assuming that no attack was imminent, yet it left a bad taste in everyone’s mouth.” [137] Two days later Pickett and two other generals, including Richard Anderson were relieved of their duties and dismissed by Lee. However Pickett remained with his division until the end and at Appomattox Lee was heard to remark in what some believed was a disparaging manner “Is that man still with this army?” [138]

George Pickett attempted to rebuild his life after the war and the task was not easy for though he applied for amnesty his case was complicated by an incident where he had ordered the execution of about twenty-two former North Carolina militiamen who had defected to the Union and been captured by the Confederates. Federal authorities thought about charging him with war crimes which resulted in Pickett fleeing to Canada. It took the intervention of Pickett’s faithful friend Ulysses S. Grant to have the charges dismissed and for Pickett to be granted amnesty by President Johnson in 1868. Grant admitted that the punishment was harsh, but wrote in his friend’s defense:

“But it was in time of war and when the enemy no doubt it necessary to retain, by some power, the services of every man within their reach. Gen. Pickett I know personally to be an honorable man but in this case his judgement [sic] prompted him to do what can not well be sustained though I do not see how good, either to the friends of the deceased or by fixing an example for the future, can be secured by his trial now.” [139]

Even so his life was difficult, health difficulties plagued him and employment was scarce, even for a man of Pickett’s stature in Virginia. He refused employment which would take him away from Sallie and his children and finally took a job as an insurance agent in Richmond. It was a job which he felt demeaning, which required that he attempt to sell insurance policies to destitute and out of work Confederate veterans and their families. Sallie wrote that he “could not come to terms with a profession that made its profits through what one colleague called “gall, gall, old man, gall and grub.” [140] Distinctly unhappy the dejected old soldier told her “I’d sooner face a canon,…than to take out a policy with me.” [141]

In 1870 he was convinced by John Singleton Mosby to visit Lee when the latter was visiting Richmond as Lee was making a final tour of battlefields and other sites. For Pickett the visit only reinforced his resentment that he felt for Lee, who he felt blamed him for the defeat at Five Forks and had ostracized him. The meeting occurred in “Lee’s room at the Ballard Hotel was icy and lasted only two or three minutes.” [142]

Mosby realized quickly that the meeting was not going well and “Sensing the unpleasantness of the meeting, Mosby got up in a few moments and Pickett followed him. Once outside the room, Pickett broke out bitterly against “that old man” who, he said, “had my division massacred at Gettysburg.” [143] Mosby attempted to assuage his friend’s feelings but Pickett “was not mollified by Mosby’s rejoinder that “it made you immortal.” [144]

George Pickett was a romantic as well as a true believer in the cause of the Confederacy. Pickett was vain, and at times self-serving, he certainly as Porter Alexander noted was a better brigade commander than division commander, a position that he desired but never excelled. His temperament at times got the better of him and he was not the equal of many of his fellow division commanders in the Army of Northern Virginia.

That being said it would be hard to prove the charges of cowardice or incompetence that some leveled at him for allegedly not being forward enough during the great charge. The fact that he retained command after the battle indicates that Lee did not believe that he had acted with cowardice, or that Lee questioned the manner in which he led the assault.

Likewise, it is unlikely that such any such action on Pickett’s part to charge further into the maelstrom would have done little more than add yet another name to the list of Confederate general officers killed or wounded at Gettysburg. The question of “how Pickett survived without a scratch, when his three brigadiers and all of his field officers but one went down. This could be done by the brief explanation that his escape was “miraculous.” [145] Edwin Coddington wrote that “it would have been better for his reputation if had been called to give his life or if the attack had been known for what it was, Longstreet’s Second Assault.” [146]

Bitter and discouraged at the end of his life he uttered his last words to Sallie’s uncle who had also served in the Army of Northern Virginia “Well, Colonel, the enemy is too strong for me again…my ammunition is all out” … He closed his eyes, and settled back as if at peace for the first time in his life. Sallie never left his side; two hours after his death they gently pried her hands from his.” [147]

Pickett’s charge was over, except for the blame, the stories and the legends, especially in the South. The failure of this disastrous tactical assault that bears Pickett’s name placed the final nail in Lee’s operational plan to take the war to the North and defeat the Federal army on its own territory. “Lee’s plan was almost Burnside-like in its simplicity, and it produced a Fredericksburg with the roles reversed.” [148] James McPherson made the very succinct observation that Pickett’s charge represented the Confederate war effort in microcosm: matchless valor, apparent initial success, and ultimate disaster.” [149]

That tactical and operational failure had strategic implications for the Confederacy; it ensured the loss of Vicksburg and forced Lee to assume the defensive in the east. “Lee and his men would go on to further laurels. But they never again possessed the power and reputation that they carried into Pennsylvania those palmy midsummer days of 1863.” [150] The repulse ended the campaign that Lee had hoped would secure the independence of the Confederacy. The Battle of Gettysburg was and it was much more than a military defeat, but a political one as well, for with it went the slightest hope remaining of foreign intervention. As J.F.C. Fuller wrote “It began as a political move and it had ended in a political fiasco.” [151]

Notes

[1] Clausewitz, Carl von. On War Indexed edition, edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1976 p.114

[2] Ibid. Clausewitz On War p.108

[3] Dempsey, Martin Mission Command White Paper 3 April 2012 p.5 retrieved ( July 2014 from http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/concepts/white_papers/cjcs_wp_missioncommand.pdf

[4] ___________. The Armed forces Officer U.S. Department of Defense Publication, Washington DC. January 2006 p.18

[5] Ibid. The Armed Forces Officer p.18

[6] Ibid. Clausewitz On War p.101

[7] Stewart, George R. Pickett’s Charge: A Micro-History of the Final Attack at Gettysburg, July 3rd 1863 Houghton Mifflin Company Boston 1959 p.94

[8] Hess, Earl J. Pickett’s Charge: The Last Attack at Gettysburg University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 2001 p. 55

[9] Ibid. Stewart Pickett’s Charge: A Micro-History p.94

[10] Wert, Jeffery D. Gettysburg Day Three A Touchstone Book, New York 2001 p.110

[11] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.548

[12] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.548

[13] Gottfried, Bradley The Artillery of Gettysburg Cumberland House Publishing, Nashville TN 2008 p.206

[14] Ibid. Gottfried The Artillery of Gettysburg p.193

[15] Longacre, Edward G. Pickett: Leader of the Charge White Mane Publishing Company, Shippensburg PA 1995 p.121

[16] Reardon, Carol The Convergence of History and Myth in the Southern Past: Pickett’s Charge in The Third Day at Gettysburg and Beyond edited by Gallagher, Gary W. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 1994 p.83

[17] Ibid. Wert Gettysburg Day Three p.297

[18] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.387

[19] Ibid. Stewart Pickett’s Charge: A Micro-History p.39

[20] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.153

[21] Ibid. Wert Gettysburg Day Three p.181

[22] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.294

[23] Ibid. Wert Gettysburg Day Three p.179

[24] Ibid. Stewart Pickett’s Charge p.132

[25] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.496

[26] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.496

[27] Huntington, Tom Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg PA 2013 p.171

[28] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.163

[29] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.499

[30] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.459

[31] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.500

[32] Alexander, Edward Porter Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander edited by Gallagher, Gary The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 1989 p.258

[33] Hunt, Henry The Third Day at Gettysburg in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War edited by Bradford, Neil Meridian Press, New York 1989 p.374

[34] Alexander, Edwin Porter. The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War edited by Bradford, Neil Meridian Press, New York 1989 p.364

[35] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.297

[36] Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet: The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 1993 p.291

[37] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.501

[38] Ibid. Alexander The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg p.365

[39] Ibid. Alexander The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg p.365

[40] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage pp.474-475

[41] Ibid. Alexander The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg p.365

[42] Ibid. Alexander Fighting for the Confederacy p.261

[43] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.313

[44] Ibid. Wert Gettysburg Day Three p.109

[45] Ibid. Dowdy, Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.264

[46] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.4

[47] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.6

[48] See Longacre Pickett pp.6-7. The myth was quite successful and it endures in some accounts of Pickett’s life and in a number of military histories including Larry Tagg’s The Generals of Gettysburg

[49] Waugh, John C. The Class of 1846 from West Point to Appomattox: Stonewall Jackson, George McClellan and their Brothers A Ballantine Book, New York 1994 pp.38-39

[50] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.7

[51] Ibid. Waugh The Class of 1846 from West Point to Appomattox p.39

[52] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.12

[53] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.378

[54] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.378

[55] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.20

[56] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.37

[57] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.264

[58] Ibid. Waugh The Class of 1846 p.457

[59] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.32

[60] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.33

[61] Ibid. Longacre Pickett pp.50-51

[62] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.51

[63] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.38

[64] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.47

[65] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and his Men at Gettysburg p.296

[66] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee an abridgment by Richard Harwell, Touchstone Books, New York 1997 p.338

[67] Freeman, Douglas Southall Lee’s Lieutenants: A Study in Command abridged in one volume by Stephen Sears, Scribner Books, Simon and Schuster, New York 1998 p.594

[68] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.408

[69] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.166

[70] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.167

[71] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.167

[72] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.483

[73] Ibid. Alexander The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg p.365

[74] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.553

[75] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.407

[76] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.193

[77] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.193

[78] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.411

[79] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.422

[80] Catton, Bruce The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p.318

[81] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.423

[82] Ibid. Stewart Pickett’s Charge: A Micro-History of the Final Attack at Gettysburg pp.193-194

[83] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.187

[84] Ibid. Stewart Pickett’s Charge: A Micro-History of the Final Attack at Gettysburg p.193

[85] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.311

[86] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.494

[87] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.425

[88] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.494

[89] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.502

[90] Ibid. Wert Gettysburg Day Three p.216

[91] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.318

[92] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.504

[93] Ibid. Stewart Pickett’s Charge: A Micro-History of the Final Attack at Gettysburg pp.238-239

[94] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.504

[95] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.425

[96] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.555

[97] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.503

[98] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.505

[99] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.505

[100] Ibid. Gottfried The Artillery of Gettysburg p.217

[101] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.220

[102] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.515

[103] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.515

[104] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.502

[105] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.448

[106] Ibid. Gottfried The Artillery of Gettysburg p.200

[107] Ibid. Gottfried The Artillery of Gettysburg p.221

[108] Ibid. Gottfried The Artillery of Gettysburg p.208

[109] Ibid. Wert Gettysburg Day Three p.211

[110] Ibid. Gottfried The Artillery of Gettysburg p.221

[111] Ibid. Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.505

[112] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.562

[113] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.262

[114] Ibid. Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.319

[115] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.317

[116] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg p.508

[117] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.451

[118] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.528

[119] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.528

[120] Fremantle, Arthur Three Months in the Southern States, April- June 1863 William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh and London 1863 Amazon Kindle edition p.285

[121] Ibid. Wert General James Longstreet The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier p.292

[122] Ibid. Fremantle Three Months in the Southern States p.287

[123] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.456

[124] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.326

[125] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.428

[126] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.428

[127] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.326

[128] Ibid Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.428

[129] ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion pp.428-429

[130] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.325

[131] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.429

[132] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.456

[133] Ibid. Waugh The Class of 1846 p.489

[134] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.354

[135] Ibid. Reardon The Convergence of History and Myth in the Southern Past: Pickett’s Charge p.76

[136] Gordon, Lesley J. “Let the People See the Old Life as it Was” La Salle Corbell Pickett and the Myth of the Lost Cause in The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History edited by Gallagher, Gary W. and Nolan, Alan T. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 2000 p.170

[137] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.375

[138] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.375

[139] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.175

[140] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.178

[141] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.178

[142] Ibid. Hess Pickett’s Charge p.377

[143] Ibid. Freeman Lee p.569

[144] Ibid. Waugh The Class of 1846 p.529

[145] Ibid. Stewart Pickett’s Charge: A Micro-History p.287

[146] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.528

[147] Ibid. Longacre Pickett p.180

[148] Millet, Allan R. and Maslowski, Peter, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States The Free Press a Division of Macmillan Inc. New York, 1984 p.206

[149] McPherson, James The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1988 p.662

[150] Ibid. McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.665

[151] Fuller, J.F.C. Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship, Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 1957 pp.200-201