Friends of Padre Steve’s World

Today another section from my Gettysburg text, this on the disaster the befell the Union Eleventh Corps north of the town on the afternoon of July 1st 1863.

Have a great day,

Peace

Padre Steve+

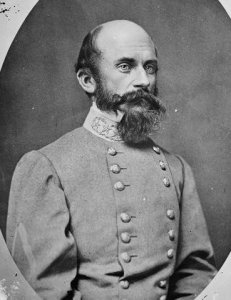

Schurz placed his own Second division under the acting command of Brigadier General Alexander Schimmelpfennig his senior brigade commander. Schimmelpfennig was a former Prussian Captain, an engineering officer, who had left the Prussian army to fight in the 1848 Revolution where he met Schurz and the two men became fast friends. When the revolution was crushed Schimmelpfennig, like Schurz fled Germany and was sentenced to death in absentia by the government of the Palatine region. He immigrated to the United States in 1853 “where he wrote military history and secured a position as an engineer in the War Department.” [1] He volunteered to serve at the outbreak of the war, and was appointed as colonel of the German 74th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Schimmelpfennig took command of the brigade when his brigade commander was killed at Second Bull Run, and he was promoted to Brigadier General by Lincoln in November 1862. According to an often told fable Lincoln supposedly promoted the German “because he found the immigrant’s name irresistible,” [2] but unlike so many other volunteer generals Schimmelpfennig was no novice to soldiering. It “took him aback to discover that American-born generals “have no maps, no knowledge of the country, no eyes to see where help is needed.” [3] He also criticized the method by which many American staff officers were selected, from their “relations, some of old friends, or men recommended by Congressmen,” [4] as compared to Molkte’s Prussian General Staff which prided itself on producing competent staff officers who could also direct troops in the heat of battle.

He too was a Chancellorsville and warned of the danger of the hanging flank and his troops were routed by Jackson’s, but as one writer noted “The brigade’s list of casualties indicates that it deserves more credit than it has been generally given.” [5] Schimmelpfennig too wanted to redeem himself and the Germans of his command as they marched to meet Lee again.

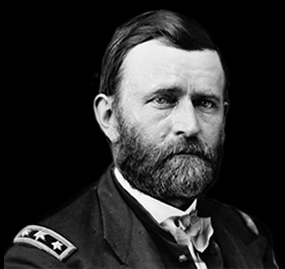

The First Division of Eleventh Corps was under the command of Brigadier General Francis Barlow. Barlow was a twenty-nine year old Harvard law graduate and Boston Brahmin was well connected politically with the more radical abolitionists of the Republican Party and had an intense dislike of Democrats. He volunteered for service and became the regimental commander and of the 61st New York Infantry. Though he did not have prior military training he “was a self-taught officer of resolute battlefield courage.” [6] His courage and competence were recognized and was promoted to Brigadier General after Antietam where he had been wounded in the groin by canister in the vicious battle for the sunken Road.

Due to his abilities the “Boy general” was convinced by his fellow abolitionist, Howard to command an Eleventh Corps division after Chancellorsville, but Barlow soon regretted his decision. Barlow, was to use modern terminology somewhat of an elitist and snob. He disliked army life and developed a reputation as a martinet with a boorish personality, who life in the army “very tedious living so many months with men who are so little companions for me as our officers are.” [7]

“Billy” Barlow was not happy with commanding the Germans, and he “disliked the beery and impenetrable Germans in his division as much as he disliked Democrats.” He admitted that he had “always been down on the ‘Dutch’ & I do not abate my contempt now.” [8] The feeling was reciprocal, his men considered him a “petty tyrant” and one wrote “As a taskmaster he had no equal. The prospect of a speedy deliverance from the yoke of Billy Barlow filled every heart with joy.” [9] As Barlow marched with his men into Gettysburg he had in his pocket a letter requesting to be given command of one of the new brigades of U.S. Colored Troops which were then being raised, something he felt was more attuned to his abolitionist beliefs and temperament.

Brigadier General Adolf von Steinwehr was another of the German’s and he enjoyed a solid reputation as a soldier. Steinwehr was a German nobleman, actually “Baron Adolf Wilhelm Augustus Friedrich von Steinwehr, a onetime officer in the army of the Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbutel.” [10] Steinwehr was a graduate of the Brunswick Military Academy came to the United States seeking to serve in the United States Army and served in the Coastal Survey as an engineer, but was not able to get a commission. He settled in Connecticut and volunteered to serve at the beginning of the war. He raised the heavily German 29th New York Infantry. He was made a brigadier general in October 1861 and took command of the Eleventh Corp’s Second division in in the summer of 1862 when the Corps was still under the command of Franz Sigel. A Pennsylvania soldier noted that Steinwehr was “accomplished and competent, and deserv[ing] of more credit than he ever received.” [11] At Chancellorsville his troops performed well and did some hard fighting before being driven back, Howard considered Steinwehr’s conduct and bearing at Chancellorsville as “cool, collected and judicious.” [12]

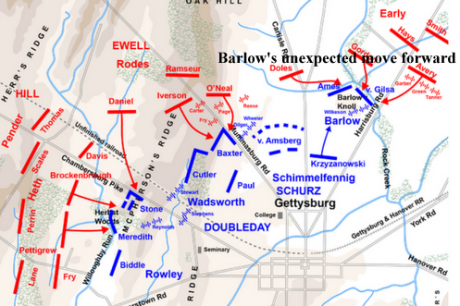

As Howard and Schurz consulted on Cemetery Hill, it was decided that Schurz would advance Schimmelpfennig and Barlow’s divisions to the north of the town in order to anchor the right flank of Doubleday’s embattled First Corps. “As Schurz remembered it, he was to take the “First and Third Divisions of the Eleventh Corps through the town and … place them on the right of First Corps, while he {Howard} would hold back the Second Division… and the reserve artillery on Cemetery Hill and the eminence east of it as a reserve.” [13] Schimmelpfennig’s division led the way through the town and deployed to the north, Barlow’s division followed moving to its right.

Schurz had two missions, to protect First Corps right flank and also to “guard against the anticipated arrival of Confederates from the northeast.” [14] Schurz intended to bring his two divisions into line each with one brigade forward and one in reserve. Schimmelpfennig’s brigade was placed at a right angle to the flank of Robinson’s division. It was Schurz’s intention that Barlow’s division “extend Schimmelpfennig’s front facing north” by keeping Ames’ brigade as a reserve in the right rear “in order to use it against a possible flanking movement by the enemy.” [15]

Both divisions were very small, especially compared to their Confederate opponents, consisting of just two brigades apiece. Schurz estimated that the two divisions numbered “hardly over 6,000 effective men when going into battle…” [16] and the ground that they had to occupy, being flat and open without and without any geographic advantage was hardly conducive for the defense, but it was necessary in order to attempt to secure the flank of First Corps and to prevent Doubleday’s command from being rolled up by Ewell’s Corps.

With the heavy pressure being put on First Corps by the Confederate divisions of Heth, Pender and Rodes; and the arrival of Jubal Early’s division of Ewell’s Second Corps Howard had few choices, and realistically Howard’s “only course was to delay the enemy.” [17] Howard has been faulted by historians Stephen Sears and Edwin Coddington for allowing Doubleday and First Corps to continue to fight on McPherson’s Ridge instead of withdrawing back to Seminary Ridge or even Cemetery Ridge during the lull in fighting early in the afternoon. [18] However, in defense of Howard, the only Confederate troops on the field when he met with Doubleday between Seminary and McPherson’s Ridge during the lull were those of Heth and Pender, as Rodes’ division had not yet arrived. As such, Howard promised to protect Doubleday’s flank without full knowledge of the situation, a promise that “would soon prove rash.” [19]

In making his decision to advance it was Howard’s intention was to get Schimmelpfennig and Barlow’s divisions up to Oak Hill to secure the right flank, but by the time his troops were moving into the open country north of the town, Rodes’s division was already there and the guns of Carter’s artillery battalion soon found the range on the Union troops. Because of this Schimmelpfennig “had to post his troops on the plain facing northwest off the right and rear of First Corps” [20] and his troops were never able to “make their link up with Robinson and the dangling flank of First Corps.” [21]

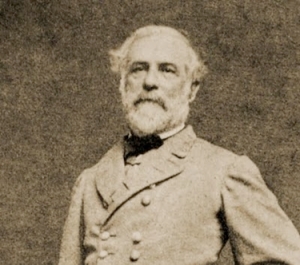

Schurz’s small divisions now found themselves facing elements of two veteran Confederate divisions; those of Robert Rodes and Jubal Early. Unlike the battle on McPherson’s and Seminary Ridge the Eleventh Corps troops did not have the advantage of good defensible ground. Likewise they had to cover a front that was much too wide for their numbers without fast reinforcements from Third or Twelfth Corps, which would not come.

Oliver Howard was counting on the timely arrival of either Slocum’s Twelfth or Sickles’ Third Corps which were in reasonable marching distance of Gettysburg, however Sickles was attempting to sort out conflicting orders from Meade and Howard, while Slocum who had just gotten the now hopelessly out of date Pipe Creek Circular waited for hours after receiving Howard’s message before putting his troops on the road to Gettysburg. Coddington argues that Howard’s hope for reinforcement at this point “was both unrealistic and unfair to the commanders of the other corps,” [22] but others have questioned that point of view, especially in regard to Slocum. Slocum’s most recent biographer Brian Melton notes that Slocum seemed to believe that “Reynolds and Howard were actively disobeying orders” [23] and wanted Slocum to do the same, and “because he deemed it contrary to Meade’s wishes, he did not want to come forward himself to take responsibility for the fight, or “of becoming a scapegoat for a lost, politically important fight someone else started against standing orders.” [24]

Melton attributes Slocum’s reluctance to take command and send his troops forward was that he had been McClellanized as a result of learned behavior in the politically charged Army of the Potomac. As such he was hesitant to jump into a situation that he had no control and then be blamed for the defeat.

“What historians see in Slocum at Gettysburg is not so much a failure of nerve (though it can be described as such) but, rather, the triumphant moment of his McClellanism. Slocum, with his tendency to absorb the philosophies of his powerful superiors, displayed conduct on day one and day two of Gettysburg that looks like McClellan in microcosm. He was absorbed with maneuver, over-cautious, focused on retreat, and scrupulously concerned with the chain of command (sometimes conveniently so). Like McClellan on the Peninsula he found excuses that kept him away from the fight, and therefore the responsibility.” [25]

What the Union command situation does show is that in a rapidly changing tactical environment that orders, no matter how well thought out, can become obsolete as soon as soon as contact is made. There it is imperative that commanders and staff officers adapt to changing situations. However, in the Army of the Potomac, which had been formed and taught by McClellan, and had endured command shake ups and the political machinations of many of its senior commanders, Slocum found that he could not take that risk. Melton wrote, “no matter what his reasons, Slocum missed an important opportunity to play an important role in the most famous battle fought on this continent, Acoustic shadows and conflicting orders kept him away from the fighting when other corps desperately needed him. Instead of covering himself with glory that day, the best he can hope for is to be quietly excused.” [26]

Major General Francis Barlow

“A Portrait of Hell”

Without reinforcements Schurz’s divisions moved north out of the town. Schurz had two missions as he moved north, “to protect Doubleday’s right and to guard against the anticipated arrival of Confederates from the northeast.” [27] to do this he had to keep his line compact enough on bad defensive ground with little natural advantage and maintain a reserve to parry any emerging Confederate threats from the northeast. The first issue was that to meet these missions Schurz only had about 6,000 troops, and these had to be spread along a line beginning at the Mummasburg Road to the York Pike. Even so there was a gap of about a quarter of a mile between Schurz’s left and Doubleday’s troops on Oak Ridge. It was the best he could do and for practical purposes the two Eleventh Corps divisions were only able to form “the equivalent of a strong skirmish line along their broad front.” [28] Had Barlow remained in place his troops would have been in a better position to receive the Confederate attack and protect Doubleday’s right flank.

However, this did not happen. Barlow did not comply with Schurz’s orders to simply extend Schimmelpfennig’s line and keep Ames’s brigade as a reserve to parry any attack on his right flank. Instead, as he moved his division through the town, Barlow secured the permission of Howard to take a small portion of high ground about a mile further north, called Blocher’s Knoll. There was a certain logic to the move, “to prevent the Rebel troops then visible to the north – George Doles’s brigade, of Rodes’s division – from occupying it and using it as an artillery platform.” [29] But the advance was to be a disastrous mistake as it left Barlow’s division exposed to Doles’s advancing troops, as well as Jubal Early’s division which then deploying for battle along the Harrisburg Road in perfect position to turn the flank of Schurz’s divisions. When Howard saw that deployment he countermanded his order that had allowed Barlow to seize Blocher’s Knoll. Howard wrote, “as soon as I heard of the approach of Ewell and saw that nothing the turning of my right flank if Barlow advanced… I countermanded the order.” [30] But the aggressive Billy Barlow continued to advance and left his own flank exposed to the attack of Early’s division which was “deployed in a three-brigade-wide battle front that was almost a mile across – and overlapped the Union line by almost half a mile.” [31]

Barlow was the only non-German division commander in XI Corps and he had little regard for Schurz. “Without consulting or even notifying his superiors, Barlow issued orders that got his division moving toward that point.” [32] Barlow advanced Colonel Ludwig Von Gilsa’s small brigade with two sections of artillery to Blocher’s Knoll placing it on the extreme right of the Union line. Instead of maintaining Ames’ brigade in reserve and slightly to the right of von Gilsa to guard against any potential flanking attack, Barlow deployed Ames’s brigade on the left of von Gilsa’s brigade facing slightly to the northwest. Barlow’s decision to do this left von Gilsa’s right flank hopelessly exposed and gave him no reserve to meet any danger on the right.

The orders that Barlow had previously had from Howard to move forward to Blocher’s Knoll were predicated on Oak Hill being unoccupied and Schimmelpfennig’s division being able to occupy it before the Confederates could do so. Barlow, on his own volition, knowing that the Confederates had taken Oak Hill and were assaulting Robinson’s division on Oak Ridge decided to advance movement placed Barlow’s division “where Barlow wished it to be” [33] and not where Schurz or Howard expected it, with disastrous results. Schurz noted:

“But I now noticed that Barlow, be it that he had misunderstood my order, or that he was carried away by the ardor of the conflict, had advanced his whole line and lost connection with my third division on the left, and…he had instead of refusing, had pushed forward his right brigade, so that it formed a projecting angle with the rest of the line.” [34]

There are still debates as to why Barlow advanced but one of the most likely explanations is that he saw the unprotected left of Brigadier General George Doles’s brigade of Georgians from Rodes division and wanted to strike them in the flank. [35]

To be sure, the position on Blocher’s Knoll “offered a cleared crown suitable for artillery and a good line of sight up the Heidlersburg Road,” [36] provided that it could be supported but it had a weakness in that “thick woods began about one hundred feet below the crest toward Rock Creek, severely limiting the field of fire in the direction of the anticipated Confederate advance.” [37] Barlow’s deployment provided Jubal Early with the perfect opportunity to execute one the hard hitting flanking attacks that had been the specialty of his old superior Stonewall Jackson.

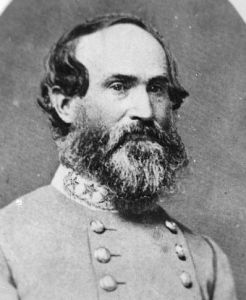

The instrument of Barlow’s division’s destruction was Brigadier General John Gordon’s brigade of Early’s division. Gordon was a self-taught soldier whose army service began when he was “elected Captain of a mountaineer company” [38] called “the Raccoon Roughs” in the opening weeks of the war.” [39] As Georgia had no room in its new military for the company Gordon offered it to Alabama where is was mustered into the 6th Alabama regiment. Even though Gordon had no prior military experience, he learned his trade well and possessed “an oratorical skill which inspires his troops to undertake anything. His men adore him….he makes them feel as if they can charge hell itself.” [40] After Manassas, Gordon was elected colonel of the 6th Alabama. He commanded the regiment until he was wounded five times in the defense of the Bloody Lane at Antietam. His final wound that day was to the face, which rendered him unconscious. He fell “with his face in his cap, and only the fact that another Yankee bullet had ripped through the cap saved him from smothering in his own blood.” [41] Before Chancellorsville the gallant colonel was promoted to brigadier general and given command of Lawton’s brigade.

Gordon’s troops hit the exposed right flank of Colonel Ludwig Von Gilsa’s tiny brigade and that force was overwhelmed by the fierceness of the Confederate assault. Von Gilsa was a professional soldier by trade who had served as a “major in the Prussian army during the Schleswig-Holstein War before immigrating to the United States” [42] from 1848 through 1850. After coming to the United States Von Gilsa supported as a singer, piano player and lecturer in New York, and on the outbreak of the war he raised and was commissioned as the Colonel of the 41st New York Infantry. He was badly wounded at the Battle of Cross Keys in the spring of 1862 and was made a brigade commander when Julius Stahel was elevated to division command. His first battle as a brigade commander was Chancellorsville where on the extreme Union right he warned of Stonewall Jackson’s flanking move, but his reports were discounted. Von Gilsa was a colorful man who won the respect of his men and “was notorious for his genius for profanity in his native German.” During the difficult retreat from Chancellorsville, Oliver Howard reminded the German Colonel “to depend upon God, and von Gilsa poured out a stream of oaths in German with such vehemence and profusion that Howard thought he had gone insane.” [43] Admired by his troops, one officer noted that von Gilsa was “one of the bravest of me4n and an uncommonly good soldier.” [44] This did not keep his new division commander Barlow from taking a dislike to him and arresting the German on the march to Gettysburg for allowing more than one soldier at a time to break ranks to refill canteens. Barlow reinstated Von Gilsa to his command at 1 p.m. just as his brigade was entering Gettysburg and beginning its march to engage the Confederates north of the town.

The position occupied by von Gilsa’s brigade “was at once a strong and dangerous position, powerful in front…but exposed on both flanks.” [45] Thus the exposed position of Barlow’s troops on Blocher’s Knoll provided the advancing Confederates the opportunity to roll up his division and defeat it in detail before moving down the Federal line to deal with Schimmelpfennig’s division. The Confederate attack engineered by Jubal Early was a masterpiece of shock tactics combining a fearsome artillery barrage with a well-coordinated infantry assault.

Colonel H.P Jones who commanded Jubal Early’s artillery battalion opened up a crossfire on von Gilsa’s brigade from its positions east of the Heidlersburg Road as Gordon’s brigade struck assisted by pressure being put forth by Junius Daniel’s brigade of Rodes division which was attacking Ames’s brigade from the northwest. The concentrated fire of the artillery added to the din and furthered the destruction among the Union men as Jones’s battalion’s fire “enfiladed its whole line and took it in reverse.” [46] The artillery fire from Jones’s battalion supported Gordon’s brigade as well as Early’s other two brigades, those of Hays and Avery as they advanced. “A prominent member of Ewell’s staff later said he had never seen guns “better served than Jones’ were on this occasion.” [47]

Von Gilsa’s outnumbered and badly exposed Union troops attempted to make a stand but were slaughtered by the Confederates; soon the brigade began to unravel, and then disintegrated. But it was not the complete rout posited by the brigade’s critics. It took “fifteen to twenty minutes of hard fighting for John Gordon’s men, assisted by some of George Doles regiments, to overrun Blocher’s Knoll” [48]One Confederate soldier later recalled, “it was a fearful slaughter, the golden wheat fields, a few minutes before in beauty, now gone, and the ground covered with the dead and wounded in blue.” [49] Another of Gordon’s soldiers noted “The Yankees…fought more stubborn than I ever saw them or ever want to see them again.” [50] Von Gilsa himself displayed tremendous courage in trying to stem the tide of the Confederate advance. He had “one horse shot from under him, but jumped onto another and desperately tried to stem the retreat. On soldier saw him ride “up and down that line through a regular storm of lead, meantime using German epithets so common to him.” [51] Despite his best efforts, just as a Chancellorsville von Gilsa was unable to hold his position and his troops fled through crowded and chaotic streets of Gettysburg to Cemetery Hill where their retreat was halted and they joined the troops of Steinwehr’s division and the other survivors of the First and Eleventh Corps troops who managed to escape the Confederate onslaught.

Brigadier General John Gordon

As Von Gilsa’s brigade collapsed Gordon “focused on the exposed right flank of Ames’s brigade” and Doles’s troops, now supported by Ramseur fell upon its left and “Ames’s outnumbered troops also collapsed” [52] even as that young and gallant commander attempted to advance his brigade to support Von Gilsa’s now fleeing troops. Barlow was in the thick of the fighting attempting to rally von Gilsa’s troops when he was wounded. Ames, the senior brigade commander took command of the shattered remnants of the two brigades when Barlow, went down. The wounded Barlow would be assisted by Gordon and “carried to the shade” of a nearby farmhouse by a member of Early’s staff. [53] Barlow recovered and after the war “he and Gordon established a friendship that lasted for the remainder of their lives.” [54]

Adelbert Ames was a native of Maine and had a stellar reputation when he entered Gettysburg. The young officer “graduated 5th out of 45 students in the Class of 1861, which completed its studies just after the fall of Fort Sumter.” [55] He was commissioned into the artillery and was wounded at First Bull Run where he was awarded the Medal of Honor. After he recovered he was commended for his service during the Peninsular Campaign. Ames then returned to Maine where he organized and commanded the illustrious 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry, and after Fredericksburg was promoted to brigadier general. “Like von Gilsa’s brigade, Ames’s came under fire from both infantry and artillery.” [56] After Chancellorsville he was promoted to brigadier general and took command of his brigade in Barlow’s division. Ames was a brave and capable leader who would continue to serve with distinction throughout the war ending up as a Major General of Volunteers and serving as one of Mississippi’s Reconstruction governors after the war. He lived a long and eventful life and was the last Civil War general to die in 1933.

Amidst the chaos of the retreat Ames worked with von Gilsa to “try to gather enough men together around a cluster of buildings along the Heidlersburg Road which served as the Adams County almshouse,” [57] and upon assuming command he succeeded in “slowing the retreat and establishing a second line when Avery’s and Hays’s brigades came crashing in on the right.” [58] However, this line too was driven back in great confusion as the brigades of Gordon and Hays, supported by Jones’s artillery hammered the thin blue line.

Schurz attempted to recover the situation by extending Schimmelpfennig’s division to the right, and advanced his reserve brigade under Polish born Colonel Wladimir Krzyzanowski to support Barlow counterattacking against Doles’s brigade. Krzyzanowski too was a refugee from Europe, coming from a region of Poland occupied by Prussia. “Kriz” as he was known to many Americans had fled to New York following the failed revolution of 1848 and made his living as a civil engineer. When war came Krzyzanowski volunteered for service, and was allowed to recruit “a multinational regiment that became known as the 58th New York Infantry, the “Polish Legion.” [59] Following service in a number of campaigns he was given command of a brigade in June of 1862.

Krzyzanowski’s brigade achieved some initial success against one of Doles’s regiments and for a time engaged in a furious short range shoot out with two more of Doles’s regiments. The opponents stood scarcely seventy-five yards apart aiming deadly volleys at one another without regard for themselves, an Ohio solider recalled “Bullets hummed about our ears like infuriated bees, and in a few minutes the meadow was strewn with…the wounded and the dead.” [60] Despite their gallantry Krzyzanowski’s troops were also rolled up in the Confederate assault when Doles and Gordon turned his flanks. Both of “Krzyzanowski’s flanks received enfilading fire and the brigade fell back across the Carlisle Road toward an orchard on the north side of Gettysburg.” [61]

As the situation deteriorated Schimmelpfennig ordered the 157th New York Infantry to support Krzyzanowski. The regiment advanced and engaged in a furious twenty minute fight, continuing the battle “in Indian fashion” until Schurz ordered them to retreat. The gallant 157th sacrificed itself buying time for others to withdraw and left over 75 percent of its men on the battlefield, when the order came, “less than fifty of the 157th were able to rise out of the wheat and follow.” [62] “So the horrible screaming, hurtling messengers of death flew over us from both sides,” recollected a New York soldier. “In such a storm it seemed a miracle that any were left alive.” [63] Krzyzanowski described the scene as “a portrait of hell.” [64]

Harry Hays brigade of Louisianans joined the assault on the collapsing Federal right while on the left Schimmelpfennig’s line collapsed under the weight of Doles’s attack, which had now been joined by the brigade of Stephen Ramseur. The proud Schimmelpfennig joined his troops in retreat. Inside the town he was unhorsed by enemy fire. In the town Schimmelpfennig was knocked unconscious “with the butt of a musket – “by the blow of a gun” – as he tried to scale a fence.” [65] By the time he regained himself Confederate troops were swarming all around, and to avoid capture he prudently “took refuge in a woodshed, where he remained in hiding the next three days.” [66] The attack of Early’s division supported by Doles and Ramseur “completely unhinged the end of the long Union line and destroyed any opportunities for resistance on that part of the field.” [67]

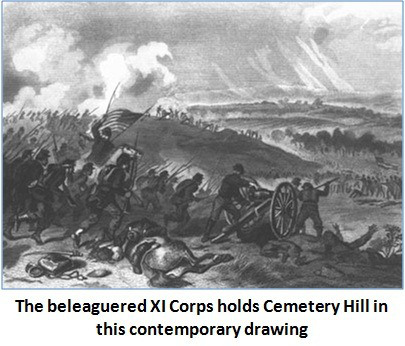

Howard was still looking for relief from Major General Slocum’s Twelfth Corps and seeing the disaster unfolding north of the town sent the First Brigade of Brigadier General Adolph Steinwehr’s division from Cemetery Hill to support the fleeing men of Barlow and Schimmelpfennig’s divisions. The small brigade of about 800 soldiers under the command of Colonel Charles Coster advanced through the town to a brickyard on the outskirts of the town. Before this small force could get into position they were hit hard by Hays and Avery’s brigades of Early’s division. The Confederates again had a massive numerical advantage at the point of attack with “eight big regiments to face Coster’s three small ones” [68] and they too were able to find an open flank and envelop both flanks of the tiny Union brigade. Avery’s brigade took them in the right flank and with both flanks turned by the advancing Confederates [69] Coster’s little brigade broke under the pressure and began to retreat leaving many prisoners to be collected by the Confederates. The commander of the 134th New York exclaimed “I never imagined such a rain of bullets.” [70] In its fight with Avery’s brigade which had the New Yorkers in a crossfire, the 134th lost some forty men killed and 150 wounded. Coster had entered the fight with about 800 soldiers but by the end of the afternoon over 550 were casualties, with “313 of them left it as prisoners.” [71] Coster survived the assault but resigned from the army a few months later never having filed and official report. [72] As the Union right collapsed and the Confederate pressure on Robinson’s division on Oak Ridge mounted, von Amsberg’s brigade, without the 157th New York found itself without support and was forced to withdraw. However, the sacrifice of Coster’s brigade “succeeded in checking the enemy long enough to permit Barlow’s division to “enter the town without being seriously molested on its retreat.” [73]

In his after action report as well as in other correspondence Barlow was acrimonious toward the German troops who he had so carelessly exposed to the Confederate onslaught on Blocher’s Knoll. He wrote “We ought to have held the place easily, for I had my entire force at the very point where the attack was made….But the enemies [sic] skirmishers had hardly attacked us before my men began to run. No fight at all was made.” [74] However, more circumspect Union officers do not back the gallant, but arrogant Boston Brahmin’s statement nor do his Confederate opponents. The Union artillery commander Henry Hunt wrote that it was “an obstinate and bloody contest” [75] while Gordon, whose brigade had inflicted so much of the damage on Barlow’s divisions wrote:

“The enemy made a most obstinate resistance until the colors of the two lines were separated by a space of less than 50 paces, when his line was broken and driven back, leaving the flank which this line had protected exposed to the fire from my brigade. An effort was made by the enemy to change his front and check our advance, but the effort failed and this line too, was driven back in the greatest confusion with immense loss in killed, wounded and prisoners.” [76]

A private of the 61st Georgia Infantry of Gordon’s brigade wrote that the Eleventh Corps troops “stood firm until we got near them. Then they began to retreat in good order. They were harder to drive than we had known them before….Their officers were cheering their men and behaving like heroes and commanders of ‘the first water’” [77]

During the retreat the redoubtable Hubert Dilger whose battery had wrought such death and destruction on O’Neal and Iverson’s brigades and Carter’s artillery while supporting Robinson’s division on Oak Ridge continued its stellar contribution to the battle. Instead of withdrawing his battery completely he halted four guns north of the town to support the infantry. “The four cannon immediately banged away at the approaching Confederate infantry and helped hundreds of Federal troops successfully escape the clutches of the enemy.” [78] When he could do no more Dilger withdrew to Cemetery Hill where his guns joined the mass of Union artillery gathering on that edifice.

Collapse and the Retreat of First & Eleventh Corps

The retreat of Eleventh Corps “southward through the streets of Gettysburg exposed the rear of the First Corps at a time when Doubleday’s troops were already having to give ground before the superior numbers represented by” [79] the divisions of Harry Heth and Dorsey Pender of A.P. Hill’s Third Corps. The First Corps had been battling Hill’s troops for the better part of the morning and for the most part had gotten the better of their Confederate opponents, inflicting very heavy casualties on the divisions of Heth, Pender and Robert Rodes. The fierceness of the Union defense of the ridges west of the town wreaked havoc on the Confederate attackers. The remnants of the Iron Brigade supported by the brigades of Biddle and Stone, Gamble’s dismounted cavalry, and Wainwright’s expertly directed artillery inflicted massive casualties on their Confederate opponents.

Notes

[1] Ibid. Pfanz The First Day at Gettysburg p.218

[2] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.63

[3] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.166

[4] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.166

[5] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.139

[6] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.38

[7] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.181

[8] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.181

[9] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.126

[10] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.162

[11] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.63

[12] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.132

[13] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.198

[14] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.74

[15] Ibid. Guelzo . Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.181

[16] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.288

[17] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.74

[18] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg pp.193-194 and Coddington p.303

[19] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.142

[20] Ibid. Pfanz The First Day at Gettysburg p.140

[21] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.166

[22] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.303

[23] Melton, Brian C. Sherman’s Forgotten General: Henry W. Slocum University of Missouri Press, Columbia and London 2007 p.125

[24] Ibid. Pfanz The First Day at Gettysburg p.143

[25] Ibid. Melton Sherman’s Forgotten General p.124

[26] Ibid. Melton Sherman’s Forgotten General p.128

[27] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.74

[28] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.76

[29] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg pp.193-194 and Coddington p.212

[30] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.77

[31] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg pp.193-194 and Coddington p.212

[32] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.217

[33] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.216

[34] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.77

[35] Ibid. From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership Greene p.78

[36] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.216

[37] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.78

[38] Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of Confederate Commanders Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge 1959, 1987 p.111

[39] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.262

[40] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command, One volume abridgement by Stephen W Sears, Scribner, New York 1998 p.41

[41] Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam Houghton-Mifflin Company, Boston and New York 1983 p.242

[42] Ibid. Pfanz The First Day at Gettysburg p.224

[43] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.127

[44] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.61

[45] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.128

[46] Hunt, Henry The First Day at Gettysburg in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War edited by Bradford, Neil Meridian Press, New York 1989 p.363

[47] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.291

[48] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.225

[49] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.79

[50] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.225

[51] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.128

[52] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.79

[53] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.188

[54] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958 p.141

[55] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.129

[56] Ibid. Pfanz The First Day at Gettysburg p.234

[57] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.187

[58] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.292

[59] Ibid. Pfanz The First Day at Gettysburg p.236

[60] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.80

[61] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.80

[62] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.186

[63] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.225

[64] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.186

[65] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.139

[66] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.477

[67] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, p.292

[68] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.190

[69] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, p.241

[70] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.241

[71] Ibid. Sears, Gettysburg pp.193-194 and Coddington p.217

[72] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.190

[73] Ibid. Pfanz The First Day at Gettysburg pp. 267-268

[74] Ibid Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.79

[75] Ibid. Hunt The First Day at Gettysburg p.365

[76] Report of Brigadier General J. B. Gordon, CSA, commanding brigade, Early’s Division, in Luvaas, Jay and Nelson Harold W editors. The U.S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg South Mountain Press, Carlisle PA 1986 p.45

[77] Ibid. Greene From Chancellorsville to Gettysburg: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership p.79

[78] Gottfried, Bradley The Artillery of Gettysburg Cumberland House Publishing, Nashville TN 2008 p.71

[79] Weigley, Russell F. A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History 1861-1865 Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 2000 p.244