Friends of Padre Steve’s World

Something a bit different. Again this is a part of one of the chapters of my Gettysburg and Civil War text, but this time dealing with two men who were the first American military theorists, Dennis Hart Mahan, the father of Alfred Thayer Mahan the great naval strategist and Henry Wager Hillock. Both men contributed to American military thought for over a century until they and their French-Swiss mentor Henri Jomini’s theories were overtaken by those of the Prussian Carl von Clausewitz.

They both are interesting characters and both had an influence on American history today ion large part due to their influence on the education of most of the generals who conducted the Civil War, and in the case of Halleck in advising Abraham Lincoln during the war.

I hope that you enjoy

Peace

Padre Steve+

Background

As we continue to examine the Civil War as the first modern war we have to see it as a time of great transition and change for military and political leaders. As such we have to look at the education, culture and experience of the men who fought the war, as well as the various advances in technology and how that technology changed tactics, which in turn influenced the operational and strategic choices that defined the characteristics of the Civil War and wars to come.

The leaders who organized the vast armies that fought during the war were influenced more than military factors. Social, political, economic, scientific and even religious factors influenced their conduct of the war. The officers that commanded the armies on both sides grew up during the Jacksonian opposition to professional militaries, and for that matter even somewhat trained militias. The Jacksonian period impacted how officers were appointed and advanced. Samuel Huntington wrote:

“West Point was the principle target of Jacksonian hostility, the criticism centering not on the curriculum and methods of the Academy but rather upon the manner of how cadets were appointed and the extent to which Academy graduates preempted junior officer positions in the Army. In Jacksonian eyes, not only was specialized skill unnecessary for a military officer, but every man had the right to pursue the vocation of his choice….Jackson himself had an undisguised antipathy for the Academy which symbolized such a different conception of officership from that which he himself embodied. During his administration disciple faltered at West Point, and eventually Sylvanus Thayer, the superintendent and molder of the West Point educational methods, resigned in disgust at the intrusion of the spoils system.” [1]

This is particularly important because of how many officers who served in the Civil War were products of the Jacksonian system and what followed over the next two decades. Under the Jackson administration many more officers were appointed directly from civilian sources than from West Point, often based on political connections. “In 1836 when four additional regiments of dragoons were formed, thirty officers were appointed from civilian life and four from West Point graduates.” [2]

While this in itself was a problem, it was made worse by a promotion system based on seniority, not merit. There was no retirement system so officers who did not return to the civilian world hung on to their careers until they quite literally died with their boots on. The turnover in the highest ranks was quite low, “as late as 1860, 20 of the 32 men at or above the rank of full colonel held commissions in the war of 1812.” [3] This held up the advancement of outstanding junior officers who merited promotion and created a system where “able officers spent decades in the lower ranks, and all officers who had normal or supernormal longevity were assured of reaching higher the higher ranks.” [4]

Robert E. Lee was typical of many officers who stayed in the Army. Despite his success Lee was constantly haunted by his lack of advancement. While he was still serving in Mexico having gained great laurels, including a brevet promotion to Lieutenant Colonel, the “intrigues, pettiness and politics…provoked Lee to question his career.” He wrote, “I wish I was out of the Army myself.” [5]

In 1860 on the brink of the war, Lee was “a fifty-three year-old man and felt he had little to show for it, and small hope for promotion.” [6] Lee’s discouragement was not unwarranted, for despite his exemplary service, there was little hope for promotion and to add to it, Lee knew that “of the Army’s thirty-seven generals from 1802 to 1861, not one was a West Pointer.” [7]

The careers of other exemplary officers including Winfield Scott Hancock, James Longstreet, and John Reynolds languished with long waits between promotions between the Mexican War and the Civil War. The long waits for promotion and the duty in often-desolate duty stations on the western frontier, coupled with family separations caused many officers to leave the Army. A good number of these men would volunteer for service in 1861 a go on to become prominent leaders in both the Union and Confederate armies. Among these officers were such notables as Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, Henry Halleck, George McClellan and Jubal Early.

The military education of these officers at West Point was based very technical and focused on engineering, civil, and topographic, disciplines that had a direct contribution to the expanding American nation. What little in the way of formal higher level military education West Point cadets received was focused the Napoleonic tactics and methods espoused by Henri Jomini as Clausewitz’s works had yet to make their way to America. Dennis Hart Mahan taught most military theory and tactics courses being taught at the academy in the formative years of so many of the men who would lead the armies that fought the American Civil War.

Many Americans looked on the French, who had been the allies of the United States in the American Revolution, favorably during the ante-bellum period. This was especially true of the fledgling United States Army, which had just fought a second war with Great Britain between 1812 and 1815, and “outstanding Academy graduates in the first half of the nineteenth century, such as Halleck and Mahan, were sent to France and Prussia to continue their education. Jomini was consider as the final word on the larger aspects of military operations, and American infantry, cavalry, and artillery tactics imitated those of the French Army.” [8]

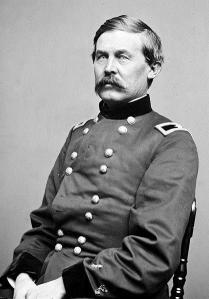

Respected but Never Loved: Dennis Hart Mahan

Mahan, who graduated at the top of the West Point class of 1824 was recognized as having a brilliant mind very early in his career, as a third classman that “he was appointed an acting assistant professor of mathematics.” [9] Following his graduation the brilliant young officer was sent by the army to France, where he spent four years as a student and observer at the “School of Engineering and Artillery at Metz” [10] before returning to the academy where “he was appointed professor of military and civil engineering and of the science of war.” [11] It was a position that the young professor excelled as subjected “the cadets…to his unparalleled knowledge and acid disposition.” [12]

Mahan spent nearly fifty years of his life at West Point, including nearly forty years as a faculty member he could not imagine living life without it. Thus he became “morbid when the Academy’s Board of Visitors recommended his mandatory retirement from the West Point Faculty” and on September 16th 1871 the elderly Mahan “committed suicide by leaping into the paddlewheel of a Hudson River steamer.” [13]

While he was in France Mahan studied the prevailing orthodoxy of Henri Jomini who along with Clausewitz was the foremost interpreter of Napoleon and Napoleon’s former Chief of Staff Marshal Ney. When we look at Mahan’s body of work in his years at West Point, Jomini’s influence cannot be underestimated. Some have noted, and correctly so, that “Napoleon was the god of war and Jomini was his prophet” [14] and in America the prophet found a new voice in that of Dennis Hart Mahan.

Thus, if one wants to understand the underlying issues of military strategy and tactics employed by the leaders of the Civil War armies, the professional soldiers, as well as those who learned their trade on the battlefield of America, one has to understand Jomini and his American interpreter Mahan.

Unlike the Prussian Clausewitz, whose writings were still unknown in America, Jomini saw the conduct of war apart from its human element and controlled by certain scientific principles. The focus in principles versus the human element is one of the great weaknesses of traditional Jominian thought.

The basic elements of Jominian orthodoxy were that: “Strategy is the key to warfare; That all strategy is controlled by invariable scientific principles; and That these principles prescribe offensive action to mass forces against weaker enemy forces at some defensive point if strategy is to lead to victory.” [15] Like Clausewitz, Jomini interpreted “the Napoleonic era as the beginning of a new method of all out wars between nations, he recognized that future wars would be total wars in every sense of the word.” [16] In his thesis Jomini laid out a number of principles of war including elements that we know well today: operations on interior and exterior lines, bases of operations, and lines of operation. Jomini understood the importance of logistics in war, envisioned the future of amphibious operations and his thought would be taken to a new level by Alfred Thayer Mahan, the son of Dennis Hart Mahan in his book The Influence of Sea Power on History.

To be fair, Jomini foresaw the horrific nature of the coming wars, but he could not embrace them, nor the concepts that his Prussian counterpart Carl von Clausewitz regarding the base human elements that made up war. “Born in 1779, Jomini missed the fervor of the Revolutionary generation and the romantic world view that inspired its greatest theorist, Jacques Antoine Guibert. He came to intellectual maturity during a period of codification and quest for stability in all spheres of life, including the waging of war.” [17] Jomini expressed his revulsion for the revolutionary aspects of war, and his desire to return to the limited wars of the eighteenth century:

“I acknowledge that my prejudices are in favor of the good old times when the French and English guards courteously invited each other to fire first as at Fontenoy, preferring them to the frightful epoch when priests, women. And children throughout Spain plotted the murder of individual soldiers.” [18]

Jomini’s influence was great throughout Europe and was brought back to the United States by Mahan who principally “transmitted French interpretations of Napoleonic war” [19] especially the interpretation given to it by Henri Jomini. However, when Mahan returned from France he was somewhat dissatisfied with some of what he learned. This is because he understood that much of what he learned was impractical in the United States where a tiny professional army and the vast expenses of territory were nothing like European conditions in which Napoleon waged war and Jomini developed his doctrine of war.

It was Mahan’s belief that the prevailing military doctrine as espoused by Jomini:

“was acceptable for a professional army on the European model, organized and fighting under European conditions. But for the United States, which in case of war would have to depend upon a civilian army held together by a small professional nucleus, the French tactical system was unrealistic.” [20]

Mahan set about rectifying this immediately upon his return to West Point, and though he was now steeped in French thought, he was acutely sensitive to the American conditions that in his lectures and later writings had to find a home. As a result he modified Jominian “orthodoxy by rejecting one of its central tenants-primary reliance on offensive assault tactics.” [21] Mahan wrote, “If the offensive is attempted against a strongly positioned enemy… it should be an offensive not of direct assault but of the indirect approach, of maneuver and deception. Victories should not be purchased by the sacrifice of one’s own army….To do the greatest damage to our enemy with the least exposure of ourselves,” said Mahan, “is a military axiom lost sight of only by ignorance to the true ends of victory.” [22]

However, Mahan had to contend with the aura of Napoleon, which affected the beliefs of many of his students and those who later served with him at West Point, including Robert E. Lee. “So strong was the attraction of Napoleon to nineteenth-century soldiers that American military experience, including the generalship of Washington, was almost ignored in military studies here.” [23] It was something that many American soldiers, Union and Confederate would pay with their lives as commanders steeped in Napoleon and Jomini threw them into attacks against well positioned and dug in opponents well supported by artillery. Lee’s assault on Cemetery Ridge on July 3rd 1863 showed how little he had learned from Mahan regarding the futility of such attacks, and instead trusted in his own interpretation of Napoleon’s dictums of the offense.

Thus there was a tension in American military thought between the followers of Jomini and Mahan. The conservative Jominian interpretation of Napoleonic warfare predominated much of the officer corps of the Army, and within the army “Mahan’s decrees failed to win universal applause.” [24] However, much of this may have been due in part to the large number of officers accessed directly from civilian life into the army during the Jacksonian period. Despite this, it was Dennis Hart Mahan who more than any other man “taught the professional soldiers who became the generals of the Civil War most of what they knew through the systematic study of war.” [25]

When Mahan returned from France and took up his professorship he became what Samuel Huntington the “American Military Enlightenment” and he “expounded the gospel of professionalism to successive generations of cadets for forty years.” [26]Some historians have described Mahan by the “star professor” of the Military Academy during the ante-bellum era. [27] Mahan’s influence on the future leaders of the Union and Confederate armies went beyond the formal classroom setting. Mahan established the “Napoleon Club,” a military round table at West Point.[28] In addition to his writing and teaching, Mahan was one of the preeminent influences on the development of the army and army leadership during the ante-bellum period.

However, Mahan and those who followed him such as Henry Halleck, Emory Upton and John Bigelow who were the intellectual leaders of the army had to contend with an army culture which evidenced “a distain for overt intellectual activities by its officers for much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries….Hard fighting, hard riding, and hard drinking elicited far more appreciation from an officer’s peers that the perusal of books.” [29]

Mahan dominated the academy in many ways. For the most part Mahan ran the academic board, an institution that ran the academy, and “no one was more influential than Mahan in the transition of officership from a craft into a profession.” [30] Mahan was a unique presence at West Point who all students had to face in their final year before they could graduate and become a commissioned officer. “His Engineering and Science of War course was the seedbed of strategy and tactics for scores of cadets who later became Civil War Generals.” [31] That being said most of what Mahan taught was the science of engineering related to war and he “went heavy on the military engineering and light on strategy” [32] relying primarily on Jomini’s work with his modifications for the latter.

The prickly professor was “respected by his students but never loved.” One student described him as “the most particular, crabbed, exacting man that I ever saw. He is a slim little skeleton of a man and is always nervous and cross.” [33] As a teacher Mahan was exceptional, but he was exceptionally demanding of his students. Those cadets who had survived the first three years at the academy were confronted by this “irritable, erudite, captious soldier-professional who had never seen combat” yet who was “America’s leading military mind.” [34]

Mahan was “aloof and relentlessly demanding, he detested sloppy thinking, sloppy posture, and a sloppy attitude toward duty…Mahan would demand that they not only learn engineering and tactics, but that every manner and habit that characterizes an officer- gentlemanly deportment, strict integrity, devotion to duty, chivalric honor, and genuine loyalty- be pounded into them. His aim was to “rear soldiers worthy of the Republic.” [35]

Mahan was one of the first American military professionals to stress the importance of military history to the military profession. He wrote that without: “historical knowledge of the rise and progress” of the military art…it is impossible to get even “tolerably clear elementary notions” beyond “those furnished by the mere technical language….It is in military history that we are to look for the source of all military science.” [36]

Mahan’s greatest contributions in for American military doctrine were his development of the active defense and emphasis on victory through maneuver. Mahan stressed “swiftness of movement, maneuver, and use of interior lines of operation. He emphasized the capture of strategic points instead of the destruction of enemy armies,” [37] while he emphasized the use of “maneuver to occupy the enemy’s territory or strategic points.” [38]

Key to Mahan’s thought was the use of maneuver and the avoidance of direct attacks on prepared positions. Mahan cautioned that the offensive against prepared positions “should be an offensive not of direct assaults but of the indirect approach, of maneuver and deception. Victories should not be purchased at the sacrifice of one’s own army….” It was a lesson that Robert E. Lee learned too late. As such Mahan prefigured future theorists such as B.H. Liddell Hart in propagating the doctrine of the indirect approach. Mahan warned: “To do the greatest damage to our enemy with the least exposure to ourselves,… is a military axiom lost sight of only by ignorance to the true ends of victory.” [39]

His emphasis on “military history led Mahan to abandon the prevailing distinction between strategy and tactics in terms of the scale of operations. He came to see that strategy, involving fundamental, invariable principles, embodied what was permanent in military science, while tactics concerned what was temporary.” Mahan believed that “History was essential to a mastery of strategy, but it had no relevance to tactics.” [40]

Mahan emphasized that “study and experience alone produce the successful general” noting “Let no man be so rash as to suppose that, in donning a general’s uniform, he is forthwith competent to perform a general’s function; as reasonably he might assume that in putting on robes of a judge he was ready to decide any point of the law.” [41] Here, Mahan’s advice is timeless and still applies today, especially in an era when many armchair generals, most without any military experience or training, especially pundits and politicians pontificate their expertise on every cable news channel twenty-four hours a day.

Mahan certainly admired Napoleon and was schooled in Jomini. Mahan believed in the principles that Jomini preached but he was not an absolutist. He believed that officers needed to think for themselves on the battlefield. Mahan preached that celerity and reason were the pillars of military success, and that “no two things in his military credo were more important than the speed of movement- celerity, that secret of success- or the use of reason. Mahan preached these twin virtues so vehemently and so often through his chronic nasal infection that the cadets called him “Old Cobbon Sense.” [42]

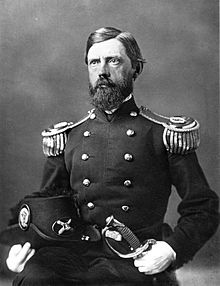

Old Brains: Henry Wager Halleck

Mahan’s teaching was both amplified and modified by the work of his star pupil Henry Wager Halleck. During his time as a cadet Halleck “achieved “a kind of strategic protégé status, even becoming part of the faculty while still a cadet.” [43] Halleck wrote the first American textbook on military theory Elements of Military Art and Science. Halleck’s book was published in 1846 and though it was not a standard text at West Point “it was probably the most read book among contemporary officers.” [44] The text was based on a series of twelve lectures Halleck had given the Lowell Institute in 1845, as at the time Halleck was considered one of America’s premier scholars as he remained for many years.

Like Mahan, Halleck was heavily influenced by the writings of Jomini, and the Halleck admitted that his book “was essentially a compilation of other author’s writings,” [45] including those of Jomini and Mahan; and he “changed none of Mahan’s and Jomini’s dogmas.” [46] In addition to his own book, Halleck also “translated Jomini’s Life of Napoleon” from the French. [47]

Halleck, like his mentor Mahan “recognized that the defense was outpacing the attack” [48] in regard to how technology was beginning to change war. As such, “five of the fifteen chapters in Halleck’s Elements are devoted to fortification; a sixth chapter is given over to the history and importance of military engineers.” [49] Halleck’s Elements became one of the most influential texts on American military thought during the nineteenth century, and “had a major influence on American military thought.” [50] Mahan’s book was read by many military leaders before, during and after the war, and some civilians, most notably Abraham Lincoln who upon entering officer sought to learn all that he could about military affairs, and whom Halleck would serve as Lincoln’s primary military advisor.

Halleck believed in and espoused Mahan’s enlightenment too, and he fought against the Jacksonian wave of populism. He eloquently spoke out for a more professional military against the Jacksonian critics of professional military institutions. Halleck advocated his case for a more professional military against the Jacksonian critics and pled “for a body of men who shall devote themselves to the cultivation of military science” and the substitution of Prussian methods of education and advancement for the twin evils of politics and seniority.” [51]

Notes

[1] Huntington, Samuel P. The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London 1957 pp.204-205

[2] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.206

[3] Skelton, William B. An Officer Corps Responds to an Undisciplined Society by Disciplined Professionalism in Major Problems in American Military History: Documents and Essays edited by John Whiteclay Chambers II and G. Kurt Piehler Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York 1999 p. 132

[4] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.207

[5] Thomas, Emory Robert E. Lee W.W. Norton and Company, New York and London 1995 p.139

[6] Korda, Michael. Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2014 p.213

[7] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.207

[8] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.197

[9] Waugh, John C. The Class of 1846: From West Point to Appomattox, Stonewall Jackson, George McClellan and their Brothers Ballantine Books, New York 1994 p.65

[10] Hagerman, Edward. The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare Midland Book Editions, Indiana University Press. Bloomington IN. 1992. p.7

[11] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.7

[12] Ibid. Waugh The Class of 1846 p.65

[13] Millet, Allan R. and Maslowski, Peter, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States The Free Press a Division of Macmillan Inc. New York, 1984 p.126

[14] Hittle, J.D. editor Jomini and His Summary of the Art of War a condensed version in Roots of Strategy, Book 2 Stackpole Books, Harrisburg PA 1987 p. 429

[15] Shy, John Jomini in Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age edited by Paret, Peter, Princeton University Press, Princeton New Jersey 1986 p.146

[16] Ibid. Hittle, Jomini and His Summary of the Art of War p. 428

[17] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.4

[18] Ibid. Hittle Jomini p.429

[19] Ibid. Shy Jomini p.414

[20] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.7

[21] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.9

[22] Ibid. Weigley The American Way of War p.88

[23] Ibid. Shy Jomini p.414

[24] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.13

[25] Ibid. Shy Jomini p.414

[26] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State pp. 217-218

[27] Robertson, James I. Jr. General A.P. Hill: The Story of a Confederate Warrior Random House, New York 1987 p.8

[28] Hagerman also notes the contributions of Henry Halleck and his Elements of Military Art and Science published in 1846 (p.14) and his influence on many American Officers. Weigley in his essay in Peter Paret’s Makers of Modern Strategy would disagree with Hagerman who notes that in Halleck’s own words that his work was a “compendium of contemporary ideas, with no attempt at originality.” (p.14) Weigley taking exception gives credit to Halleck for “his efforts to deal in his own book with particularly American military issues.” Paret, Peter editor. Makers of Modern Strategy: For Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1986 p.416.

[29] Van Riper, Paul The relevance of history to the military profession: An American Marine’s View in The Past as Prologue: The Importance of History to the Military Profession edited by Williamson Murray and Richard Hart Sinnreich Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York 2006 p.35

[30] Ibid. Millet and Maslowski For the Common Defensep.126

[31] Ibid. Robertson General A.P. Hill p.8

[32] O’Connell Robert L. Fierce Patriot: The Tangled Lives of William Tecumseh Sherman Random House, New York 2013 p.6

[33] Pfanz, Donald. Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier’s Life University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London 1998 pp.25-26

[34] Ibid. Waugh, p.64

[35] Ibid Waugh The Class of 1846, pp.63-64

[36] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.220

[37] Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 1993 p.30

[38] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.14

[39] Ibid. Weigley The American Way of War p.88

[40] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.220

[41] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State pp.221

[42] Ibid. Waugh The Class of 1846 p.64

[43] Ibid. O’Connell Fierce Patriot p.11

[44] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.14

[45] Marszalek, John F. Commander of All of Lincoln’s Armies: A Life of General Henry W. Halleck The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London 2004 p.42

[46] Ambrose, Stephen E. Halleck: Lincoln’s Chief of Staff Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge and London 1962 p.6

[47] Weigley, Russell F. American Strategy from Its Beginnings through the First World War. In Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age edited by Paret, Peter, Princeton University Press, Princeton New Jersey 1986 p.416

[48] Ibid. Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.14

[49] Ibid. Weigley, American Strategy from Its Beginnings through the First World War. In Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age p.417

[50] Ibid. Ambrose Halleck p.7

[51] Ibid. Huntington The Soldier and the State p.221